How Technology Is Helping Decode Animal Language

Scientists have been trying to “translate” animal languages — an ambitious project that could shape our relationship with different species.

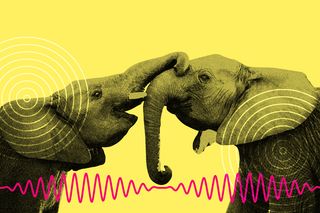

In 2017, a group of scientists were struck by a startling realization – sperm whale vocalizations, that sound like clicks, resemble Morse Code to a great extent. Enter: AI. It sowed the seeds for an ambitious project — the Cetacean Translation Initiative, or Project CETI — that would use artificial intelligence to translate these whale sounds such that humans would be able to understand them. The introduction of tech into studying animal behavior not only helps us understand them better — but also, paradoxically, helps reveal our own limits as a species. This could go one of two ways: enable greater conservation efforts, or instil a hubris that could use the newfound knowledge of animal communication against them.

It is not just whale communication that has been the subject of translation initiatives. Researchers have created an algorithm that can assess the emotional states of pigs based on their calls, while others used audio and video recordings to unearth the context of bat calls. Until recently, attempts at understanding animal language have been primarily based on observation. The advent of technology has considerably widened the scope of research studies. “Combined, these digital devices function like a planetary-scale hearing aid: enabling humans to observe and study nature’s sounds beyond the limits of our sensory capabilities,” Karen Bakker wrote in her book, The Sounds of Life: How Digital Technology Is Bringing Us Closer to the Worlds of Animals and Plants. However, these devices have also generated vast amounts of data that are difficult and time-consuming to manually parse through.

The scientific community is, thus, increasingly using technological tools including drones, recorders, robots and AI to study the calls of a range of species, from chickens and rodents, to cats and lemurs.

The New York Times reported that machine learning algorithms can identify subtle patterns that might escape human researchers. These programs can distinguish between individual animal voices. They can also recognise the separate animal sounds made in different circumstances and break down these calls into smaller parts, considered an important step in decoding meaning. For example, DeepSqueak — a software that uses deep learning algorithms to identify, process and categorize ultrasonic squeaks of rodents, that are otherwise inaudible to the human ear.

Related on The Swaddle:

Scientists Discover a ‘Hidden Language’ by Analyzing Chimpanzee Vocals

This could aid conservation efforts in new ways.Project CETI is working on decoding the syntax and semantics of sperm whale — considered federally endangered in the United States — communication. Meanwhile, the Earth Species Project (ESP) — a non-profit dedicated to using AI to decode non-human communication — is cataloging the calls of Hawaiian crows and even attempting to build new technology that could help humans talk to animals.

With reports emerging of how climate change is affecting bird populations — reducing the complexity and variation of birdsong and causing “‘song culture’ to break down” — the ESP’s study on the critically endangered Hawaiian crows, grown in captivity, has several implications for conservation. It could help researchers study lost bird calls and reintroduce those considered most critical to captive birds. “The end we are working towards is, can we decode animal communication, discover non-human language… Along the way and equally important is that we are developing technology that supports biologists and conservation now,” Aza Raskin, co-founder and president of the ESP, told The Guardian.

The wealth of information that lies masked in animal communication can also be instrumental in understanding social dynamics within species. When machine learning was used to analyze around 36,000 chirps of naked mole rats, researchers found that each mole rat had its own unique vocal signature and each colony had its own dialect, which is passed down over generations. In cases when a colony queen was deposed, these dialects were erased. With a new queen, a new dialect would emerge.

Further, research suggests that decoding animal language also has the potential to help us understand “the evolution, neurobiology and cognitive basis of human language.” Several scientists have challenged popular beliefs that animal communication is completely unrelated to the evolution of human language, pointing to how songbirds “show a human-like capacity to learn complex vocal patterns.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Some Monkeys Change Their “Accents” When In Other Species’ Territory: Study

However, decoding animal language poses several difficulties. As Raskin noted, animals do not only communicate through sound, which means we will have to translate across different modes of communication, as in the case of bees that inform others of a nectar source through a “waggle dance”. Further, such research efforts raise a more fundamental question that has polarized the scientific community over the years: Do animals even possess language?

Bakker highlighted in her book how indigenous communities have long been aware of animal communication. She noted that researchers studying animal communication have faced stiff opposition from the Western scientific community that has “historically dismissed the idea of animal communication outright.”

“So many of the attempts to teach primates human language or sign language in the 20th century were underpinned by an assumption that language is unique to humans, and that if we were to prove animals possess language we would have to prove that they could learn human language. And in retrospect, that’s a very human-centered view,” Bakker told Vox, adding that research today is taking a very different approach and has led to fascinating discoveries, including how elephants have a different signal for threatening and non-threatening human beings.

While potentially being able to understand animals could help deepen our relationships with our surrounding world and guide protection efforts, Bakker also raised several ethical concerns that may arise. “…[T]he ability to speak to other species sounds intriguing and fascinating, but it could be used either to create a deeper sense of kinship, or a sense of dominion and manipulative ability to domesticate wild species that we’ve never as humans been able to previously control,” she said. Researchers have noted that AI may not be able to completely unlock the complex nature of animal languages. Still, it provides a glimpse of what might be possible in the future.

While we are still a while away from a Google Translate equivalent for animal languages that can decode the nuances of intra-species communication, technology, especially machine learning, is keeping this hope alive. The ability to understand animal languages could open up a realm of possibilities, potentially shaping conservation efforts, determining our future relationship with other species, and even offering insights into the evolution of human language itself.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

What the ‘Dead Internet Theory’ Predicted About the Future of Digital Life