Growing up, we learned the simile: “as hardworking as an ant.” Well, turns out, it was all a lie. Not all ants are hardworking. Many of them are freeloaders.

Published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a new study provides exciting insights into the evolution of “social parasitism” in ants — the origin of which had left Charles Darwin confounded as well. “By what steps the instinct of [the species] originated, I will not pretend to conjecture,” Darwin had written in Origin of Species.

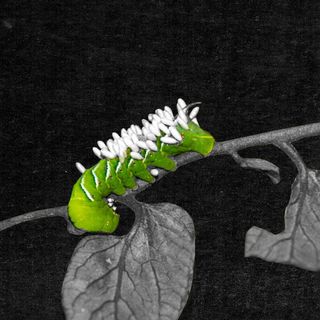

In nature, social parasitism occurs when individuals exploit existing collaborative networks of one’s species or a closely related one. It’s, basically, a shortcut to sustenance — falling back on the existing cooperation in a community instead of contributing to it. Interestingly, some publications have compared social parasitism in ants to the plot of the Academy Award-winning movie Parasite.

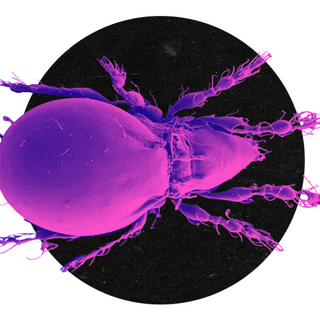

About 2% of more than 16,000 known ant species and subspecies are estimated to be social parasites. Among them, scientists believe the Formica species of ants to include the most social parasites of any ant genus — making them the “perfect candidate” for the present study.

“Identifying the conditions associated with ant life history and their transition from cooperative colony life to exploitative social parasitism is important for understanding how changes in behavior contribute to speciation,” Christian Rabeling, associate professor of organismal evolutionary biology at the Arizona State University, who co-authored the study, said in a statement.

Among the different parasitic behaviors exhibited by ants, one is “temporary social parasitism,” where the parasites depend on their hosts “only during the establishment of new colonies.” Temporary social parasitism comes into play when queen ants, having lost their ability to breed new colonies, invade other queens’ nests, kill them, and raise their offspring.

Related on The Swaddle:

A Species of Ants Have the Ability to Shrink, Regrow Their Brains: Study

While attempting to trace the genetic timeline for the phenomenon’s evolution, the researchers found that species that demonstrate temporary social parasitism share a common ant ancestor that lived about 16 million years ago. “We demonstrate that social parasites evolved from an ancestor that lost the ability to establish new colonies independently,” the study notes.

But given that Formica ants have been around for much longer than that, the researchers concluded parasitism in the species developed later.

Two million years after, yet another form of social parasitism developed: “dulotic social parasitism.” Just like temporary social parasitism, here too, a queen raids the nest of another and raises their offspring. Once the colony has enough workers, the queen launches an attack on yet another nest, and once their queen is killed, the parasite army either raises the offspring as their own — or eats them. The researchers believe this form of social parasitism exists to help the invading ants acquire food quickly, improve numbers, and reduce competition for territory.

The youngest class of social parasites, according to the researchers, are “permanent social parasites.” In this version of parasitism, the invading queen and the host queen live together — with the former focusing on reproduction and the latter carrying on their lives as usual.

“This was a moment of clarity… It’s like you have all these different mosaic pieces. You place one stone here, another stone there. Then there’s a new observation that adds yet another piece to the mosaic,” Rabeling noted, adding that “once you put in the evolutionary time context, all of a sudden, you can see the entire picture.”

“For us, this is a fantastic period right now… Just the ability to ask these questions was probably the most exciting part of this study,” Rabeling noted about the study, adding: “It’s deeply satisfying.”