I Self‑Diagnosed My Autism Because Nobody Else Would. Here’s Why That Needs to Change.

Researchers are calling people like me the lost generation of autistic adults, urging doctors to bring us into the health care system. But it’s not so easy.

In late 2018, at the age of 30, I read the description of a 13-year-old autistic girl:

“Chloe is a very intelligent girl, but concerns were raised after she started becoming increasingly sensitive and anxious. Chloe is very concrete and very honest. She struggles increasingly in social situations…”

As I read further, tears began rolling down my eyes. In Chloe, I could see myself. All my life, I had struggled to relate to people, find commonalities, and belong to a group. People labeled me as too intelligent, or too naive; too honest or too unwise; too concrete or too idealistic. Family elders often explained my social difficulties away by saying I was “different.” This had left me feeling confused, lonely, misunderstood, and misjudged for as long as I could remember. Now, with Chloe, for the first time in my life, I related to another human being.

Naturally curious about autism, I dove into investigation over the next few days. Interestingly, when I referred to literature authored by non-autistic people, I felt even more disconnected: autism seemed to be a scary, bad disease. But the more I read literature written by autistic people, the more excitedly I thought, “ET home!”

To confirm, my parents, brother, husband, and I did some screening tests. All pointed to autism. We went through the DSM-5 criteria for autism and made detailed notes of how it described me: my difficulties with people, my reaction to new situations, my perception of sounds.

Related on The Swaddle:

A Peek Into How Kids With Autism Experience Social Situations

Armed with this data, I went to a clinical psychologist for confirmation. Within 10 minutes, the clinician, angrily and rudely dismissed me by declaring I thought too much of myself. The sixth psychologist, while kinder than the first five, ended up misdiagnosing me with Social Communication Disorder. After three more hurtful psychiatrists, and lots of wasted money, I finally made peace with the fact that I am autistic, and my self-diagnosis would have to be enough.

I have, in this interim year, also connected with many autistic people around the world on Twitter and Facebook. I find that I am not alone. Many of them, just like me, have led very traumatic lives, replete with emotional bullying, and in some cases, sexual abuse, because their environments were hardly ever supportive. For autistic people, a lack of social identity leads to vulnerability and victimization. They are gaslit for reacting to the bombardment of their senses and are at high risk for chronic diseases. High prevalence of psychiatric disorders, suicide, and pre-mature mortality are now documented in autistic people. Yet, a significant number of us go through an entire childhood without anyone noticing that we’re struggling and need help. We try to cope by camouflaging: suppressing our autistic behaviors and copying those of others. We do it to look ‘normal,’ to be accepted, and to avoid being ostracized for looking odd. But in the process, we acquire dangerously high levels of stress. Then, in adulthood, through a chance encounter with a diagnosed autistic person — through reading, watching a program, face-to-face meeting — we see ourselves reflected. We seek a formal diagnosis, but again do not receive one.

Some researchers are finally noticing this trend. They call us the lost generation of autistic adults and are urging psychiatrists to identify us and bring us into the health care system. They acknowledge that a formal autism diagnosis can facilitate the development of self-awareness, social identity, and self-compassion. It can empower an individual to assert themselves with others, and receive timely access to services and help.

But systemic barriers in understanding and identifying autism make diagnosis a privilege, reserved for the lucky few.

Although autism has been documented since the 1930s, systematic research into its presentations and impact in adulthood only began in the 1970s. Since then, most autism research is conducted by non-autistic researchers, with little attention given to aspects that actually matter to autistic adults, such as developing novel self-care regimens, navigating relationships at work, and with romantic partners, advocating for themselves.

Related on The Swaddle:

Depression Is Three Times More Common Among Young Adults With Autism

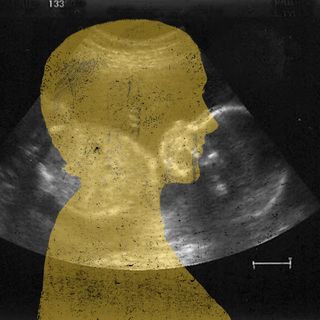

Diagnostic criteria allowed for autistic adults to be diagnosed only since 1994. But, unfortunately, diagnostic criteria have always been based on observations of external behaviors and have failed to consider cognition, which is the core of the lived autistic experience. For example, if an autistic child is interested in dinosaurs, their brain would pour in all its resources to learn about dinosaurs. The child would care for little else other than dinosaurs. They would become a sort of an expert on dinosaurs, over a short period of time, due to this deep focus. But the clinician, mostly a non- autistic person, therefore, looking at the situation from a non-autistic lens, and — blind to the cognitive reasons behind the child’s behaviors — would only see that the child is not engaging with people because of their interest in dinosaurs. They would term the learning style of the child an obsession, instructing the parent to stop all exposure to dinosaurs. When parents act on the clinician’s recommendations, the child’s brain, unable to understand the basis for change and unable to re-organize its resources so suddenly, gets overwhelmed, leading to tantrums. Concerned parents and clinicians would, however, only see that the child is behaving inappropriately, and explain it through underdeveloped skills that are so well stigmatized for autistic individuals.

Due to these stigmatized views on autism, most clinicians are not attuned to the characteristic manifestations of autism. Clinicians tend to be on the lookout for explicitly visible features, as decades of autism research has taught them to be, unaware of the presentations in people with high IQs, typical speaking abilities, and females. For example, I dealt with my autism discovery how the child in the above example dealt with dinosaurs, but my mode was reading: something which is considered ‘normal’ and therefore, was used as a basis for clinicians to quickly discard my self-diagnosis.

Clinicians also don’t know the various ways we camouflage. One psychiatrist told me I wasn’t autistic because I could make eye contact; an an inability to make eye contact is widely considered one of the main superficial markers of autism. But this understanding doesn’t take into account that many autistic people, including me, because we are constantly being told to look at people and talk, learn to look at other parts of people’s faces when talking, such as the mouth, which people often mistake for eye contact.

In addition, clinicians lack training in differentiating autistic features from mental health conditions. For example, autism shares many characteristic features with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, such as social withdrawal, lack of eye contact, sleep disturbances, and fatigue, so it is easy to misdiagnose an autistic person. Clinicians need to educate themselves on the nuances of autism, and stop relying on research often spearheaded by non-autistic people to identify and help autistic individuals.

Yet another barrier to diagnosis is the access to diagnostic tools for clinicians. Currently, the ADOS – 2 — an assessment of communication, social interaction, play, and restricted and repetitive behaviors — is the only valid diagnostic tool for adults. But it is susceptible to false negatives in the case of females and adults who have high intellectual and/or camouflaging abilities, often reflecting the biases of the scientists who created them. Its cost, which can run up to two lakh rupees, can also discourage clinicians from investing in it, especially in a country like India, where it is not covered by government service or insurance.

Related on The Swaddle:

It Takes Effort, Strategy For People With Autism to Pass as Neurotypical

The autistic community is responding to this vacuum in service by accepting, validating and mentoring self-diagnosed adults. Finding the autistic community has resurrected me. I have finally found my tribe: people who help me understand myself and make sense of my life experiences. Unlearning and relearning about myself is a difficult process made rewarding by their support. They instinctively know to provide me with the help I have always craved for but never received. They teach me self-care methods especially suited for me. Most importantly, they encourage me to unapologetically be me. My mental health, and therefore my relationships with immediate family, have improved. I have become more assertive about my unique care needs because now, I feel empowered.

However, in order for autistic consumers and non-autistic health care providers to co-exist, we require a symbiotic relationship. If clinicians truly intend to serve autistic people (and most of us need medical/therapeutic help), they must actively seek out autistic perspectives and relearn about autism. Indian writer Tito Mukhopadhyay and British artist Stephen Wiltshire are shining examples of how autistic people are shattering all stereotypes. We have demonstrated that we don’t need a cure because — in autism advocate and livestock rights activist Temple Grandin’s words, “we are different, not less.” Thus, clinicians must give up the pathology paradigm: the assumption that the majority of the population has a ‘normal’ or healthy brain and autistic people have an impaired brain because theirs diverges substantially from the norm, and accept the neurodiversity paradigm in the context of the social model of disability, which “seeks to change society in order to accommodate people living with impairment; it does not seek to change persons with impairment to accommodate society,” according to People With Disability, Australia.

A number of us have created resources for people to understand what autism means to us, how it affects us, and how we’d like to be supported. These must be made core training materials on autism. When in doubt, ask us using #AskingAutistics on social media platforms. We are only too happy to educate you.

And most importantly, accept self-diagnosis. Considering the mountain of social stigma attached to the label of autism, it is worth taking an adult exploring their autism seriously.

As your paradigm shifts, your foundations of right and wrong may be shaken and you may find yourself in a constant battle with your social conditioning. That’s a sign that you’re headed the compassionate way. Remember, this earth is the only place bequeathed to us, just like it is for you. We belong here too. Let us be.

Rakshita holds a master's degree in intellectual and developmental disabilities from University of Kent, UK, and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from Bangalore, India. She has over 10 years of experience facilitating learning for children and adults, across socio-economic categories and support needs, and currently teaches autistic students with a focus on developing their self and social identity. She has presented research on inclusive education in national and international forums.

Related

The Most Traumatic Thing About Abortions Is the Judgment