ILO Report Clarifies the Gendered Burden of Unpaid Carework Around the World

Child care and housework would equal 9% of global GDP — if women were paid for it.

A new report out of the International Labour Organization examining the gender gap in paid and unpaid carework concludes that if progress continues at the current rate, it will take 210 years to equalize the burden of carework between men and women.

This is due, in part, to the fact that the demand for care work — everything from child care, to elder care, to caring for an ill or disabled family member, to cooking and cleaning — is set to increase by 0.2 billion in the next 15 years. It is also due to the dismally slow progress toward egalitarian divisions of carework in the past two decades: Between 1997 and 2012, the gender gap in time spent in unpaid care declined by only seven minutes.

“This extra demand for paid care work – if it remains unmet – is likely to continue to constrain women’s labour force participation, put an extra burden on care workers and further accentuate gender inequalities at work,” the report concludes.

Globally, women perform 76% of unpaid care work — this is three times more than men. On a daily basis, this boils down to women spending 4 hours and 25 minutes per day on care work, against 1 hour and 23 minutes for men.

“Over the course of a year, this represents a total of 201 working days (on an eight-hour basis) for women compared with 63 working days for men,” the report explains. “This is equivalent to 2.0 billion people working 8 hours per day with no remuneration. Were such services to be valued on the basis of an hourly minimum wage, they would amount to 9 per cent of global GDP, which corresponds to US$11 trillion (purchasing power parity 2011).”

What is most striking about the report is how remarkably consistent the burden of carework is on women across the world. Across Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific, Europe and Central Asia, women spend 262 to 272 minutes on unpaid care work each day. (The Arab States region was the global outlier, with women spending 329 minutes a day doing unpaid carework; men in the region do 70 minutes a day of unpaid carework — notably, six minutes more a day than their counterparts in Asia and the Pacific.)

It’s not a matter of economic wealth. The difference in time spent on carework per day between high-income and low-income countries was a mere five minutes for women. Intriguingly, it’s the middle-income countries in which the gulf between men and women’s involvement in care work is widest; in these countries, women spend 267 minutes a day in care work, versus men’s 66 minutes. On a daily basis, in both low- and high-income countries, women do less care work than women in middle-income countries, and men do more carework than men in middle-income countries.

This suggests something beyond income is at play. Middle-income countries are often in flux, economically and socially. India is a case-in-point. Technically classified by the World Bank as middle-income, and acknowledged globally as a nascent economic and geopolitical powerhouse, India struggles with deeply patriarchal beliefs about gender roles, even as traditional forms of carework support (extended or joint families) diminish. Women are better educated, but only 27% of them participate in the workforce. The cultural conflict between women’s aspirations and realities is often pointed to as the reason why Indian women are the most stressed in the world.

The great irony is that globally, most women (70%) want to be working in paid jobs — and surprisingly, 66% of men agree, according to an ILO-Gallup survey last year. But fewer men agreed when children enter the picture.

“The presence of children under 15 years of age in the household does not significantly influence women’s preferences regarding women being in paid work, but it does influence men’s preferences regarding whether women should or should not work at paid jobs,” the report found. “Mothers are no more likely than childless women to prefer women to stay at home and care for the family, whereas fathers are more likely than childless men to want women to stay home.”

In other words, a predominating male mindset that it’s totally okay for a woman to be educated and work outside the home until it’s time to have children — then her place is at home, taking care of family — is inhibiting women’s participation in the workforce. Perhaps not profound findings (any woman in India could tell the authors that), but it’s nice to have data that conveys how broadly this attitude is ingrained, and how inhibiting it truly is — to women, and to economies.

Mindsets are difficult to change, and the report focuses on specific policies as surer ways to spread carework more equally between the genders. Specifically, the report examines government expenditure as a percent of GDP on care policies such as pre-primary education services; long-term care services and benefits; and maternity, disability, sickness and employment injury benefits. India devotes less than 0.5% of GDP combined to the kind of policies that would equalize the burden of carework; India also has one of the lowest rates of employment of women with care responsibilities.

Expenditure is, perhaps, the key word. While earlier this year India mandated six months of paid, maternity leave for female employees, the government has been criticized for offering no subsidy to employers to help offset cost — a gap that has led to recent reports that the new maternity leave policy is likely to exclude women from the workforce, rather than include them.

But while attitudes are slow to change, they shouldn’t be written off entirely, and the report notes the role policy can play in moving the needle. “The design of leave policies has enormous potential to promote men’s uptake of leave and reduce the gender gap in unpaid care work,” the report notes.

Someone, please send Maneka Gandhi a copy.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

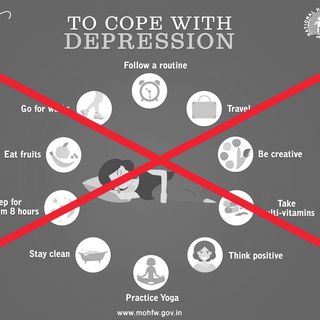

Health Ministry Attempts to Destigmatize Depression, Fails Miserably