In a breakthrough that could save lives by reducing the wait-time for lung transplants, scientists have converted blood type-A lungs into blood type-O — a universal donor blood group. They achieved the conversion before a “transplant” — that is, the lungs were placed in plasma to simulate an actual transplant to observe the reaction. The result was minimal antibody damage, which means that the newly converted lungs were accepted by the plasma.

“Together, these findings have the potential to improve fairness in lung allocation for transplantation,” the research, published in Science Translational Medicine, noted.

“These patients require organs that must be compatible [with] their major cell surface antigens. The process to find compatible organs is not trivial,” the authors note in their paper. Indeed, many people with end-stage lung disease rely on lung transplants as their only option for survival. In India, the already difficult process is made harder due to the lack of availability of compatible donors — as finding donor lungs that match the same blood group is the most crucial step in the process. Unsuitable blood type-lungs can be rejected –– leading to fatal antibody reactions in hosts.

But finding compatible donors is notoriously difficult and many patients can often succumb before they access the lungs they require. To reduce transplant wait times and speed up the life-saving process, scientists have found a way that could potentially revolutionize organ transplants.

Related on The Swaddle:

Indian Doctors Perform Asia’s First Lung Transplant for a Covid19 Patient

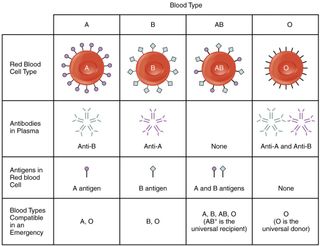

The experiment utilized two enzymes — FpGalNAc deacetylase and FpGalactosaminidase — to turn the blood type, “neutral.” There are four blood groups: A, B, AB, and O. Each has a set of antibodies and antigens that differentiate one from another. Antigens in red blood cells (RBCs) determine what blood type someone has, and antibodies attack what they detect as foreign antigens.

Blood group A, for instance, has an “A” antigen (A-Ag) and an “anti-B” antibody — meaning that it would reject blood with the “B” antigen. The O blood group is known as a “universal donor” group because it has no antigens — therefore, antibodies from white blood cells in the host will not attack, or reject, any transfusion or transplant from this blood group. However, while people with this blood group can be donors to all blood groups, they can only be recipients of type-O blood groups because it has anti-A and anti-B antibodies, which rule out receiving blood or organs from the three other groups.

AB-type blood is the inverse of O: it is a universal recipient because it contains A and B antigens, meaning that it would not reject any blood group because not only does it have both A and B antigens, it also does not have any antibodies.

Related on The Swaddle:

What Is Going On With Organ Donation in India?

Here is where the latest study comes in. The enzyme pair works to remove antigens from the donor lungs’ blood; essentially turning it into an “O” blood type. This could have huge implications for medicine: it could drastically reduce waiting periods for people in need of compatible donor lungs. Not only that, it could prevent precious donor lungs from going to waste due to not being compatible with people in need of them.

“Donor organ allocation is dependent on ABO matching, restricting the opportunity for some patients to receive a life-saving transplant,” the paper states. In this experiment, the scientists successfully converted eight blood group A lungs into blood group O lungs by removing the “A” antigen. They did not observe any adverse effects on lung health.

Simulating a transplant “ex vivo,” or outside the body, scientists further observed that the antibody response from the host O blood type plasma was minimal (remember, O blood type can only receive from another O blood type), “suggesting that this technique may reduce antibody-mediated injury in vivo.“

“The enzymes removed greater than 99 and 90% A-Ag from RBCs and aortae,” the authors further noted. With these promising results, scientists hope to study long-term effects after transplants in mice before moving forward to human beings.