In a First, Scientists Create ‘Synthetic Embryos’ That Could Help Heal People

“The embryo is the best organ-making machine and the best 3D bio-printer — we tried to emulate what it does,” the researchers said.

The embryo represents a certainty of life: human eggs mature with the help of sperm, presenting the early stage of development in the womb. But they also carry within an ineffable promise and possibility of discovery — even throwing open the question of the origins of life itself. Scientists grew synthetic embryos without the support of eggs, sperms, or the home of a womb in a world’s first, potentially paving a new way of recovery and healing for people.

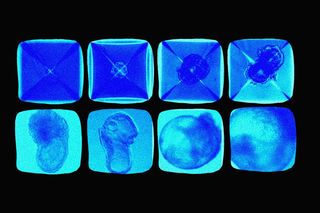

Published in the journal Cell on Wednesday, the research details the discovery by scientists at Israel’s Weizmann Institute. They took stem cells — cells that work as raw material for all other cells with specialized functionsto generate — from mice to assemble a structure that mimics an embryo in appearance and function. The tiny embryo-like organisms were developed over eight days in a Petri dish, with a beating heart, a gut tube, and the early stages of a brain.

“Remarkably, we show that embryonic stem cells generate whole synthetic embryos, meaning this includes the placenta and yolk sac surrounding the embryo,” said Prof Jacob Hanna, from the Weizmann Institute, who led the effort. “We are truly excited about this work and its implications.”

Hanna refers to two critical implications here: the synthetic embryo which is a living structure created without fertilized eggs offers insights into the way organs and tissues form in early stages. More importantly, the design of synthetic embryos in itself could be studied further to grow tissues and organs, which can be used for human transplantation in the future. “The embryo is the best organ-making machine and the best 3D bio-printer — we tried to emulate what it does,” Dr. Hanna said. The researchers found the synthetic model displayed a 95% similarity as compared to the natural mouse embryos; they were similar in shape, size, and even gene expression of cells.

The problem statement here is a shortage of organs for transplantations; countries the world over are struggling to perform life-saving transplants that could save millions of people. Within the scientific community, the answers involve exploring stem cell research and finding ways to grow living organs that could meet this need. Which explains efforts to create the world’s first monkey embryos containing human cells, or building mechanical wombs that allow natural mouse embryos to grow outside the uterus for several days.

But the use of artificial embryos, ones that are mechanical, birthed in tubes and dishes and not the human body, comes laden with several technical and ethical questions. One concerns the potential of exploiting animals for research purposes. The other is about affording a “moral status” to living creatures, and the subsequentrights and duties of an organism that develops mental capacities between those of ordinary animals and humans. How do we determine what is mortal, and what is not? Moreover, researchers are supposed to adhere to the requirement that lab-grown human embryos have to be destroyed within 14 days. But can science simply create or destroy something that is living?

Related on The Swaddle:

Study Sheds New Light on Why IVF Embryos Fail to Develop

Then, “if pigs or monkeys are eventually developed with humanized features, it could cause major public opprobrium, perhaps setting back public acceptance of science significantly,” researchers from the University of Oxford wrote of this dilemma last year.

The design of the current synthetic embryo does bypass some of these concerns.

Essentially, scientists knew of the self-renewal ways of the stem cells, but the effort to program them in a way such that it forms entirely new organs was still a laborious task. “We managed to overcome these hurdles by unleashing the self-organization potential encoded in the stem cells,” said Dr. Hanna.

They reprogrammed the stem cells to their earliest stage, by using an electronically-controlled device the team had developed for similar research last year. “That device keeps the embryos bathed in a nutrient solution inside of beakers that move continuously, simulating the way nutrients are supplied by maternal blood flow to the placenta, and closely controls oxygen exchange and atmospheric pressure,” explained ABC News.

The base structure that was experimented upon were mouse stem cells that were cultured for years, and not a fertilized egg. This addresses some concerns related to using natural embryos for research purposes.

There remains a need for regulation and discussion around the extent and scope of the research. If we do start growing synthetic human embryos, science would essentially be harvesting synthetic donor human beings.The ethics of experimentation, personhood, and morality sit uncomfortably together. “Synthetic human embryos are not an immediate prospect. We know less about human embryos than mouse embryos and the inefficiency of the mouse synthetic embryos suggests that translating the findings to human requires further development,” said Dr. James Briscoe, a principal group leader at the Francis Crick Institute in London, who was not involved in the research.

“Now is a good time to consider the best legal and ethical framework to regulate research and use of human synthetic embryos and to update the current regulations.”

Moreover, how exactly do stem cells know what to do? How do they grow, self-assemble, and find their way into designated spots in an embryo? The researchers plan to address these mysteries, ones that walk the line between ethics and innovation.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Dwindling Insect Population May Trigger ‘Plant Wars,’ Research Shows