Researchers put together a first-of-its-kind resource collating more than 33,000 unique viral populations in the human digestive tract. This is an impressive feat, because these viruses are extremely hard to detect and differentiate between. The resultant observations are now published in the journal Cell Host and Microbe.

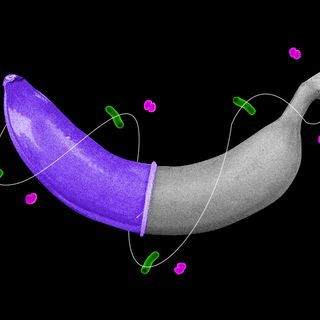

Each organ system in the human body contains 10-100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells, including bacteria, viruses and fungi. This is called a microbiota, and the genes these cells harbor are collectively called a microbiome. Of all microbiomes, the gut microbiome plays a pivotal role in human physiological function and health. The gut microbiome primarily consists of bacteria, but also includes viruses, fungi and protozoa.

To understand the diversity and value of gut virus populations, scientists utilized data from 32 studies spanning a decade, which all looked at gut viruses in around 2,000 healthy and sick people in 16 countries. They detected virus genomes (viromes) which helped them identify more than 33,000 unique viral populations. They also utilized machine learning on known viruses to help identify the unknown viruses.

Related on The Swaddle:

What Gut Bacteria Does with the Food and Drugs We Give It

Primary findings stated people living in non-Western countries had higher virus diversity than their Western counterparts, which means factors such as diet and environment have an impact on virus diversity. As with gut bacteria, age significantly influences gut virus diversity, increasing significantly from childhood to adulthood, then decreasing after senescence (65 years).

“A general rule of thumb for ecology is that higher diversity leads to a healthier ecosystem,” Ann Gregory, lead author and researcher at the Ohio State University, said in a statement. She added, “We know that more diversity of viruses and microbes is usually associated with a healthier individual. And we saw that healthier individuals tend to have a higher diversity of viruses, indicating that these viruses may be potentially doing something positive and having a beneficial role.”

The importance of this research, according to lead author Matthew Sullivan, is that 97.7% of the identified viruses are bacteriophages, or viruses that infect bacteria. Bacteriophages play a role in ‘phage therapy’ — a century old idea involving the use of bacteriophages to kill bad bacteria. Generally, doctors prescribe antibiotics to get rid of harmful bacteria, but microorganisms evolve and become immune to antibiotics. Plus, taking antibiotics can also disturb the gut microbiome, which leads to health problems. Sullivan states that phage therapy can be an alternate, effective means to fight these ‘super-bugs’ and cataloging the gut virus population is a necessary step to further aid its development.

“We’ve established a robust starting point to see what the virome looks like in humans,” study co-author Olivier Zablocki, a postdoctoral researcher in microbiology at Ohio State, said in a statement. “If we can characterize the viruses that are keeping us healthy, we might be able to harness that information to design future therapeutics for pathogens that can’t otherwise be treated with drugs.”