Facts are the truth, but they make for drab convincing arguments. New research published in PNAS suggests that rationality and facts alone will not help change a political or ideological opponent’s mind. What really works — despite individual intuition and logic — is both logic and subjective, personal experiences. Together, these tactics make a political argument compelling.

“The problem is that facts — at least today — are themselves subject to doubt, especially when they conflict with our political beliefs,” researchers write, referring to the global fake-news epidemic that has polarized both facts and opinions. “Because personal experiences are seen as truer than facts, they furnish the appearance of rationality in opponents, which in turn increases respect. We suggest that this effect is because personal experiences are unimpugnable; first-hand suffering may be relatively immune to doubt.”

In order to arrive at this conclusion, researchers conducted two meta-analyses for 15 different studies (including one study of more than 3 lakh YouTube comments) that compared fact-based and experience-based strategies with respect to how often each changed opponents’ minds. The first meta-analysis examined the value of rationality versus personal experiences in fostering respect, and the second looked at rationality versus personal experiences in increasing people’s willingness to interact with political opponents. Both meta-analyses showed personal experiences both gained the opponent’s respect and increased their willingness to interact.

Related on The Swaddle:

How to Talk Progressive Politics With a Conservative Family

In specific, researchers highlight personal experiences surrounding harm as those that command the most respect, especially when harm/witnessing harm happens to someone with who the opponent can identify with. This is because the moral wrongness of harm serves as a common ground that two people can use to build a rational consensus.

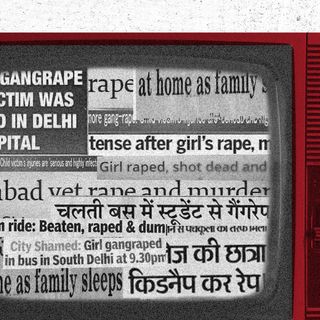

However, unlike facts, narratives are volatile and manipulable — hence providing a shaky foundation upon which to base beliefs. For example, a protester can use terrifying experiences with police violence to help a pro-government individual see the problems with an authoritative government. But similarly, an anti-vaxxer can use the pain of coincidentally losing a child after vaccination to dissuade a sympathetic friend from immunization, even if the child’s death was completely unrelated to vaccines.

Researchers agree that stories of harm can polarize both positively and negatively, regardless of the respect and level of engagement they initiate. Yet, the fact remains that personal experiences of harm do catapult social movements and can be used for good.

“What works is showing someone you’re concerned about your future, your family’s future, and the future of the nation,” Kurt Gray, the paper’s lead author, tells Inverse.“Show you’ve got genuine concerns. This is really hard to do in a conversation where you’re arming yourself for war. But it’s what we need to do.”