In Conversation: On the Song Lyric That Aestheticizes Rape Culture

The team discusses pressing events that say something about our culture, and why it matters. Today, the ethics of dramatizing rape culture.

The team discusses pressing events that say something about our culture, and why it matters. Today, we talk about the ethics of dramatizing rape culture.

A song from the forthcoming movie Liger poses pertinent questions about entertainment and its depictions of rape culture. The lyric in question is “Bhagwaan ke liye chhod do mujhe” (please let me go, in the name of God). Many have pointed out how this is an ignorant and thoughtless depiction of rape culture, to an extent that the song serves to normalize abuse.

We look at the ethics of turning dialogues into aesthetics, the misogyny embedded within the industry, and how rape culture is unwittingly reproduced through pop culture.

*

SK: Jawaani teri aafat. Bhagwaan ke liye chhod do mujhe.

The song knows what it’s doing. It’s playing on the peak, ‘70s-80s Bollywood storyline of the woman in distress, clutching onto a piece of clothing, surrounded by “bad men” about to harass and rape her. The scene is charged with a hint of urgency — awaiting the “hero” to come and save the “heroine.” The violence is pushed to the sidelines; the helplessness, power imbalance, and abuse are mere afterthoughts to this dramatized narrative.

The problem is not so much the use — modern tracks have looked at classics and adapted versions infused with rap and hip-hop and beats one too many. It’s the intent: the most recognizable symbol of a rape scene in a movie is positioned in a song. Meant to spark, what, amusement? Humor? Interest and entertainment? The two actors are swaying and spinning around beaches, in bedrooms, and over rocks amid the sea. Ananya Pandey saying it in an “oopsie” way appears jarring, given the association of the line with femininity and violence. The problem with the intent is it sees the line as an aesthetic, as if the “dialogue” is a caricatured phrase uttered in movies and the realm of fiction alone, when we know it corresponds to the realities of violence and abuse. The faux modernity of the song if anything manufactures an aesthetic of rape, asking for clicks and likes, and views all while it represents a devastating violence. Some words, some narratives demand tenderness and care, and compassion. This isn’t about “catchy” or edgy phrases, or even the freedom of artistic expression. But using a moment of emotional and physical violence for aesthetic reasons in a song shows the haunting rigidity of rape culture – a rot that makes and remakes itself, first through words, now through songs.

DR: The point of using a line typically attributed to a woman escaping a man’s unwarranted sexual advances, in a song depicting consensual desire, isn’t something I can wrap my head around. But given Bollywood’s aversion to logic, I’m not particularly bothered by the incoherence at play here. Instead, what’s more disturbing about the lyrics — particularly in the age of trending TikTok-esque videos — is a woman’s pleas being trivialized endlessly as people lip-sync to it in their reels.

Every now and then, we get catchy songs from reels stuck in our heads. Annoying as that might be, it’s a rather unavoidable downside of consuming social media. But with Aafat, the risk isn’t just of encountering an earworm; it’s that mocking the helplessness of a woman attempting to escape her abuser can end up normalizing rape culture — perhaps, unconsciously — in the process. Women’s safety is already a major cause of concern in most parts of India; rape culture, too, has long been prevalent in the country. The instant (and constant) reel-ification of the song holds the power to further distort an already dark reality for women in India. As such, the inclusion of the line in this song — which, to make matters worse, belongs to yet another movie that celebrates hypermasculinity — is irresponsible, to put it mildly.

RN: The controversy is outrageous, but sadly unsurprising. Liger is promoted as a pan-Indian film, which makes the rape culture it perpetuates in the song even more dismal. Its director’s history with misogyny and sexism is familiar to anyone with a perfunctory knowledge of Tollywood pop culture. The same culture dialed up a hundred notches is what makes the pan-Indian movie phenomenon itself that much more concerning. It caters to the lowest common denominator across all states and stands to bring overt rape culture back into full swing just as we’ve made slow, baby steps in recognizing and moving away from it. Telugu action heroes are rife with hypermasculine energy that exists in conjunction with damsels in distress. Liger, whose actor propelled into Bollywood stardom through a pan-India vehicle, is from this very tradition; in Tollywood, the film that propelled him to fame was Arjun Reddy. The valorization of violently misogynistic men, then, isn’t new — its blatant proliferation across the country, however, might be.

AS: Even when films flop, songs go on to live for long in the psyche of listeners and viewers. And songs that objectify women, with their catchy lyrics and music, go on to become chartbusters and superhits. These songs, visualized with stars who are equivalent to gods to their fans, clearly send a signal that it is okay to harass a woman this way. Filmmakers may not directly endorse the behaviors picturized in such songs, but they are clearly aware of the whistles and eyeballs they will grab, hence they continue to make them — the pointed reference in the song in question in Liger is a case in point of how rape culture operates. What they are not bothered about is these songs being used in real life to eve-tease and harass women by the very men who whistled to it in the theaters. At the very least, these songs provide men with a language, with a vocabulary, for their creepy, lecherous behavior. The fact that their hero does it with a free pass probably also provides them with the confidence to carry out their creepiness.

Related

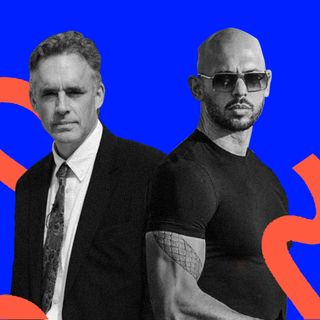

How the Rise of Internet Father Figures Threatens Women, Gender Minorities