In ‘Euphoria,’ Lexi Is a Bad Friend Who Makes Good Art

Lexi’s much-awaited play drags all her loved ones through the truth-wringer without their permission — but at least it’s great art. She is TV’s foremost bad art friend.

This article contains spoilers for season 2, episode 7.

A New York Times essay that briefly took the Internet by storm went like this: two writer acquaintances fell into a long-drawn legal battle over the contention that one of them unfairly used the other’s real-life as inspiration for a story. But there’s more to it: the inspirer donated a kidney to a stranger and expected a lot of praise from it. The inspiree used that — specifically, a Facebook post talking about the donation — as inspiration for a character with a white savior complex.

The essay sparked a heated debate about the “bad art friend” and on the ethics of using real people’s lives as fodder for storytelling, particularly the uncomfortable bits. It was further complicated by the fact that the writer may have had a point there. That, in fact, their observation was bang on and made a larger point about something: the finer points of human nature, selfishness, narcissism, race dynamics, call it what you will.

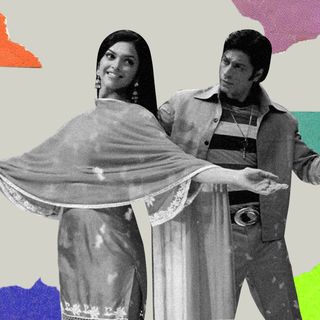

In the penultimate episode of Euphoria’s second season, it is Lexi’s time to shine. As the underdog, the only person certified by audiences worldwide as Normal or RegularTM, Lexi has spent most of her time in Cassie’s shadow. Waiting in the wings — both literallyand metaphorically — for her time in the sun. In this episode, we finally see her long-awaited, highly-anticipated debut as director-writer-actor of a tell-all, an autobiographical account of high school life, a Bildungsroman about growing pains. And a lot of pain there is. The problem, however, is that most of the pain explored here is not her own.

Many, many friends and real-life acquaintances are dragged through the truth-wringer against their will. Most significantly, Cassie gets her comeuppance, as she watches herself through her sister’s unforgiving eyes. It isn’t pleasant. Do many of these people deserve to know the truth about themselves? Undoubtedly. But like this? Not so much. A public spectacle is made of everyone’s lowest points, their moments of deep vulnerability with Lexi that only she was supposed to be privy to. And now, everyone and their mothers are in on it too. The characters on stage are thinly veiled caricatures of real people sitting in the audience at that very moment — which makes this whole enterprise not just Lexi’s story, but a public dragging of everyone she’s ever known; airing dirty laundry, Broadway-style.

I was rooting for Lexi until this point. Far be it for me to hold a high school student to a higher artistic ethical standard than most adults are held to, but really, what was she thinking? The Nate-inspired dance number with its phallic imagery and homoerotic charge nailed it, yes (give Ethan all the awards!). But the play’s merits demand questions about whether it was worth it. Do fellow teenagers deserve to have all their secrets out in the open this way? Arguably not. The showstopper about Nate was perhaps the only thing that was justified — not because it poked fun at Nate, but because it was vague enough to be about anyone, and it pulled the rug from under high school hyper-masculinity that everyone takes far too seriously for their own good.

On the flipside, however, the whole spectacle may have been a public outing of Nate from a closet he wasn’t sure he was in.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Mothers in ‘Euphoria’ Deserve Their Own Backstories

It’s the same way that audiences were privy to Rue sharing a vulnerable anecdote about her dad with Lexi on the roof of a pop-up shop, specifically asking her not to tell anyone. They’re privy to Maddy’s analog “Marta” crawling into bed, sobbing, with Cassie or “Hallie” and breaking down about her parents fighting. Most of all, they were privy to Cassie’s deep, devastating insecurities through an unforgiving lens by her own sister. Lexi has no right over these stories or vulnerabilities. These are not, and have never been, her narratives to narrate.

The production value was great, sure. You can make good art while being a bad art friend, it seems. Lexi put up a play to tell her story, and in the process, used others’ stories as a crutch for her own insecurities. She was worried about being an absent friend to Rue: the result is oversharing Rue’s story of addiction and grief where it was not her place, and presumably without permission. She was insecure about her body and her place in the high school totem pole: the result is a brutal takedown of her own sister’s unhealthy coping mechanism to deal with their father’s absence in their lives.

This isn’t to dismiss the validity of Lexi’s feelings in all this. She isn’t perfect. Her whole thing is that she’s normal. And swallowing a tide of ugly feelings back into your gut for your own sanity in high school is… normal. It really is. It is to say, however, that using other people’s pain and trauma to tell your own coming-of-age story is exploitative. What was she thinking? To see her sensible character arc reduced to another cliché– the “I’m not like other girls” trope — is the most disappointing destination for all character arcs. Second only, perhaps, to Kat’s storyline being reduced to that of a snarky yes-woman sidekick to Maddy. No matter how beautifully done, it’s wrong.

Granted, everyone knew Lexi was busy this whole season taking notes from scenes going on in her real life. Granted, detaching herself from unpleasant situations and processing them as a third person is her way of coping. Granted, too, that Lexi has no true friend or support system — other than Fezco, most recently — to hear her out. She had to make a point, and she had to make it the biggest, most unforgettable one ever made. But it simply leaves a bad taste, considering that none of the people in her story are dead or safely distant. Everyone is forced — without permission — to confront the worst or darkest parts of themselves through someone else’s gaze. A gaze that, most importantly, they trusted.

This may be inevitable in autobiographical narratives. Lexi may just be a budding Sylvia Plath-esque artist whose magnum opus is based on what she knows best, and if it involves dragging real people from her own life down, so be it. I love Sylvia Plath and if Lexi was real, I probably would have loved her too. I loved her play. It is an exploration of adolescent femininity, loneliness, grief, loss, confusion, and it’s her right to tell it the way she wants to.

But the big question at the heart of the ‘Bad Art Friend’ debacle was: don’t all writers or artists mine their personal lives for art? Isn’t it inevitable collateral damage? Maybe so, and it’s hard to argue otherwise. But in the context of Euphoria, it makes Lexi so much more pretentious than she needed to be; our own view of her character and her view of herself finally diverging. Where audiences may have once thought of Lexi as a sympathetic, real person — the smart, kind underdog who doesn’t get her due — Lexi views herself as smarter, kinder, and more interesting than her peers by virtue of being the underdog. Unfortunately, if she needed her peers’ deepest secrets to bolster her own story, maybe she just isn’t that interesting in her own right.

I don’t blame her, however. This is, actually, a realistic characterization of a certain type of girl in high school. We’ve all either known a Lexi or been a Lexi ourselves. I know I have. The reason I hate what she did so much is because there was a time when I might have wanted to do the same thing. It’s not like I have her artistic prowess to actually pull it off, but the point is that publicly taking down peers that make you feel less interesting or relevant should ideally be left to the daydreaming corners of the imagination. That it was actualized takes Lexi into another terrain altogether, one that is unfamiliar and unexpectedly vicious.

But, well, at least her friends and her mother are happy for her. The same cannot be said for Cassie and Nate — and it remains to be seen whether this moment of stardom is worth the potential ruin of her relationship with her sister, arguably the only one who shares her experience of loneliness and abandonment. Who will be left for Lexi after Cassie? For that matter, who will be left for Cassie after Lexi? I blame Sam Levinson, for once again not according teen girls a shred of empathy when it comes to each other. Is Lexi a bad art friend? Undoubtedly. The trouble is, she didn’t have to be, but now, that’s all she will ever be.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Woe Is Me! “My Friends Judge My Boyfriend for Being Short. How Do I Ignore Their Mocking?”