India Has Run Successful Vaccination Drives Before. An Immunization Expert Tells Us What Went Wrong This Time

“For any country, a successful vaccination drive is where people who need a vaccine, get the vaccine.”

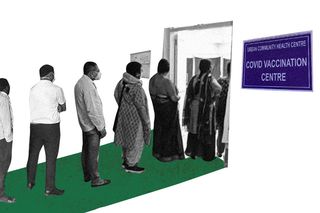

In January 2021, India said it was kicking off the world’s largest vaccination drive, as it began administering Covid19 vaccines to healthcare and frontline workers. By April 2021, everyone above the age of 18 — about 600 million people — could start registering themselves for the vaccine. India’s reputation as the world’s foremost vaccine producer and its success with past immunization campaigns for polio and smallpox meant the country had the experience and robust infrastructure in place.

Now, the nation is reeling under a severe vaccine shortage and a slowed immunization campaign, as experts point to a lack of preparedness, particularly during the second Covid19 wave. From vaccine production by private companies to vaccine registration by beneficiaries, the process is mired in confusion and chaos.

The Swaddle spoke to public health expert Dr. Chandrakant Lahariya to understand the challenges in the Covid19 immunization program. Dr. Lahariya, an epidemiologist and immunologist, was involved in India’s 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccine deployment plan. Between 2008-13, he advised the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare on new vaccine introduction while drafting the country’s national vaccine policy and plan to strengthen routine immunization.

The Swaddle: What makes a successful vaccine drive for a country like India? What factors should be kept in mind?

Dr. Chandrakant Lahariya: For any country, a successful vaccination drive is where people who need a vaccine, get the vaccine. That is what determines the success; other things are processes.

The situation is: India is not able to deliver or scale up the [Covid19] vaccination program to the extent it could have — current level of roll-out is far below the potential. The universal immunization program started in 1978. So, India has four decades of experience in delivering vaccines as part of routine immunization efforts as well as in conducting a few large-scale campaigns, such as for polio elimination — where in each round, 200 million children would be vaccinated — and also for other diseases such as measles and rubella campaigns.

Also, in the last decade, the immunization services in India have matured; vaccine cold chain storage capacity has improved, the adverse event following immunization (AEFI) recording and reporting is strengthened, vaccinators are regularly being re-trained — all these factors which make us confident that India would do really well in rolling out any vaccination program. That’s why in this context, when we are seeing the country struggling to reach out to people for Covid19 vaccination, it requires a reflection.

One of the key differences between the Covid19 vaccination and the traditional universal immunization program is that this is the first time the vaccination is being targeted for the adult population. The vaccines under routine immunization programs are delivered for children; however, Covid19 vaccines are for adults. But the principles remain the same. In the ongoing Covid19 vaccination drive, we have seen the different challenges in different phases. When the vaccination drive was launched, [starting January 16, when healthcare workers were vaccinated first], there was hesitancy and then when it was opened to everybody older than 45 years, then it was more demand than supply of vaccines available. Now, we are in a situation where the supply is really shorter than the demand.

In any program, be it a vaccination program or any other [public health] program, our focus has to be on ensuring supplies first before planning for delivery. That is where we need to work on.

TS: Why didn’t India emulate a similar model of national immunization for Covid19?

DR. L: I’m not sure what a similar model would mean during this pandemic. But a key thing would be that India is already using the immunization network that has been created over the last few decades. However, we also need to understand that the challenge is very different this time. When we say India vaccinated over 27 million children every year, those children come to seek services on a rolling basis. For Covid19, the demand is coming together. We have used much of the infrastructure — like cold-chain capacity, protocol to deal with [adverse events].

TS: What have been the challenges so far with the three-phased Covid19 vaccination policy?

DR. L: The childhood vaccines in India are delivered through a central-sponsored program: the central government procures the vaccine, they cover the cost of the vaccine, and the state government delivers.

While a similar approach has been followed for the target population of 45 years and older, the strategy for people between 18-44 years makes the entire drive confusing. This is also the first time state governments are expected to pay for and purchase of the vaccines. The state governments have to compete to buy vaccines from the same pool from which the private sector will buy.

The other aspect is that most states have a really weak procurement system for medical supplies. All these put together, the biggest challenge is going to be the availability of the vaccine because the country definitely needs more vaccine doses than is currently available. It’s time to reflect and examine and learn how best we can move forward. There are of course learnings that can help in scaling the drive.

TS: Can you elaborate on the learnings?

DR. L: One key learning is that we need to always use good, effective communication strategy while rolling out the vaccine drives. Vaccine hesitancy [faced in the early part of the Covid19 vaccination drive] could have been avoided if focused and targeted communication was used all through the process.

Secondly, the success of any program lies in assured provision. Currently, people are turning up for vaccinations, and they are being told there is no availability — that is a big deterrent. So, first, assure the supply, and then invite people.

Thirdly, state governments do not have the necessary experience in purchasing vaccines, now that they have to compete against the private sector for getting vaccines, it is going to be very challenging.

Fourth, the state governments did not budget for the cost of Covid19 vaccine. Now, if they don’t make vaccines free, people have to bear the cost, and if that happens, it will be very disappointing. If the states make a decision to provide vaccines free, which they should, it may derail their already stretched budgets. It is likely that state spending on vaccines might mean cut in the budget for other social sectors.

Fifth, India has done fairly well in using the system to respond to adverse events following immunization, but it needs to further strengthen its response.

Lastly, in India’s polio campaign and other mass campaigns, there was a lot of learning on how to engage community members and civil society organizations for improved coverage. These learnings should also be looked at [now].

TS: What determined the success of previous immunization drives, such as the pulse polio campaign?

DR. L: In addition to the aforementioned factors, one key aspect was that the pulse polio campaign was based upon a high level of community participation and of frontline workers, like ASHA and Anganwadi workers, who were mobilized to help with administering the vaccine.

Secondly, during the polio campaign, the government developed micro plans — [facilitated by] local health centers — these planned initiatives intended to use the health workforce optimally to ensured that every habitation and every child was covered. And actually, it did help to increase and sustain the polio vaccination coverage. These learnings are now already being used to deliver vaccines under routine immunization programs and Mission Indradhanush.

Another factor was the program focused upon reaching the unreached — the target children who were the most in need and if not prioritized, might have been excluded had the government not designed the focused interventions accordingly.

With Covid19 vaccination, one of the key areas that should be given attention is that there is a risk of the current strategy introducing vaccine inequity. This means that people who need the vaccine — the poor, vulnerable migrant workers, construction workers, slum dwellers — are likely to be left out, the way the program is going on. The way they need to get registered, the way vaccines are in short supply, and the way the private sector has an advantage in getting the vaccines [is introducing inequity].

One of the key approaches, in my opinion, has to be that the government needs to take special measures to make sure that the people who are at the highest risk [of exclusion] are also covered. As an example, it could be a useful approach to adopt a mobile vaccination strategy for slum dwellers or sites where construction workers and migrant laborers are situated. The United States has done the mobile vaccination strategy — in general to increase vaccination sites and vaccination access. This, along with other approaches, should be followed in India. The current fixed-site strategy needs to be supplemented by a mobile-based approach, where vaccine could reach the people to ensure the people most vulnerable receive the vaccine.

Taking a mobile vaccination in a village, where 1,000 or even 500 people live, is a fairly logical and potentially efficient strategy. People would have easier access, they don’t have to use transport modes and it could help in maintaining physical distancing at vaccination sites — so that kind of approach needs to be thought out.

I wouldn’t recommend door-to-door vaccination, because we know that there are adverse events and individuals need to be watched for 30 minutes — that is the duration when most adverse events can happen. [though a few very rare, i.e. blood clots may take a few days and weeks to develop] But I would recommend vaccination closer to the people, in a way that facilitates the process, is something everyone would expect.

TS: Covid19 is the first time a vaccine beneficiary is registering online. What are the opportunities and challenges with tech-based governance during a health crisis?

DR. L: The need for the registration requiring internet connectivity on smartphone, devices, or laptops was a potential challenge [in vaccine uptake], but walk-in is allowed for people above 45 years. But this might create a problem for people between 18 to 44 years, who mandatorily need to register on the portal to get vaccinated. It might create a problem in making a decision for taking the vaccine.

More thinking and planning are needed here. Especially, now when vaccination is for all adults, suitable relaxations [in tech-based solutions] would be needed to facilitate coverage.

TS: Has vaccine hesitancy, or skepticism, been different during the pandemic than in relation to earlier campaigns?

DR. L: It’s hard to compare because the importance of childhood vaccination is known — these vaccines are in use for a long time and people get their children vaccinated across the world. Adult vaccination is very different from childhood vaccinations. We know that the world over the coverage of adult vaccinations — for example, flu shots or Hepatitis B or other shots recommended for adults — the coverage remains low for multiple reasons. One, these vaccines are expensive, and not easily available. In most set-ups, the coverage of adult vaccination is low.

What is important to know is that in a setup like India, where adult vaccination at a large scale is offered for the first time, we need to have a stronger communication tool, awareness about these vaccines, and address vaccine hesitancy.

TS: How does the varied vaccine pricing/liberalization strategy — where some vaccines are sold in the private market, some through the states and Centre — influence the perception and success of the vaccination drive?

DR. L: This is a period in which people have already faced hardships, and thus expecting them to pay for the vaccine is an additional barrier that may make them a bit more reluctant. Especially in the public sector, people find it difficult to access the government centers, because of long queues and past experience, and in that case, they have to choose a private sector [site] — if there are three or four adult members, each in need of two jabs, it is going to be a substantial cost for the family. Vaccines are a public good, which economists agree that the governments have to pay on behalf of the people, from the pooled resources. That’s what nearly all countries, except India, are doing.

In the ongoing pandemic, the cost should have been borne by the government. The government could have purchased the vaccine and even the service charge ideally should be paid by the government.

TS: Would you have advised distributing the vaccine by age, oldest to youngest, in this scenario?

DR. L: There cannot be just one criteria, but I would say that more than the age, it is the risk profile of a population group that would matter. In the end, everyone needs to be vaccinated, but I am a little uncomfortable about opening up vaccination for the entire population in one go, especially when we don’t have enough supply. A better approach would have been to open up the vaccination in a phased manner as we have more vaccine and factoring in the higher-risk population: so even in the 18-44 year bracket, if people have comorbidities, people on the frontlines, people who work in construction or other sectors should have been given priority rather than opening up for everyone in that age group. If there is a steady supply, then it would be a different story.

TS: What do you think is the most feasible way to deal with vaccine shortage?

DR. L: We can deal with this shortage by one, engaging with manufacturers to scale up their products’ capacity; however, that will take a few months.

Secondly, another potentially powerful approach could be that the technology for vaccines developed in India is made widely available for any vaccine manufacturer, in any part of the world, who wants to engage in the production. In return, they can provide major proportion of their production to India, at an agreed cost. I think, that could be a game changer.

Third is, we need to increase the gap between the shots of Covishield to 12 weeks. We know that works better than the shorter gap and it will free up a few million additional doses. People can wait for four additional weeks which will allow the shots to go to more people.

Fourth, in my opinion, the state governments should be given a free hand to selecting the population sub-group, in the age bracket of 18-44 years, which they would want to prioritize for vaccination. Doing it well is more important [in any vaccination program] than symbolic doing it for all but badly.

TS: What are the unique Covid factors19 that would have made a vaccination roll-out in India easier or more difficult than before?

DR. L: I wouldn’t say there is something unique about India — as we now know, the virus behaves in a similar way for a global population. What advantage India has, as far as vaccination programs are concerned, is that we had a vast network to facilitate vaccine roll-out. We have a vast number of vaccinators; the programs in public sectors are highly trusted; and India has a large number of vaccine manufacturers that produce vaccines in a large volume. All of these are very conducive and helpful to make us believe in the effectiveness and success of the Covid19 vaccine roll-out. All that is needed is slightly better short- to medium-term planning, looking at the supply side, ushering some financial resources, doing microplanning to assure success.

The vaccine program is a sum total of policy formulation, strategy development, ensuring supplies, and actual vaccine delivery at the grassroots level. To make it successful, we need to work on all, and not any one component. Till now, there has been a lot of attention on policy; but it’s time we look at detailed strategy, supply issues, and also improve delivery.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

How Toxins, Pesticides Travel Through the Food Chain to Our Plates