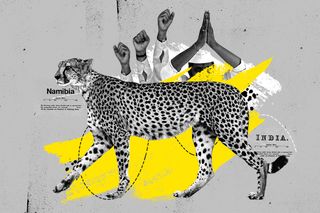

India’s Cheetah Reintroduction Plan Is Fraught With Political Symbolism, Short on Scientific Rigor

The very idea of cheetah reintroduction belies a heroic, political symbolism aimed at boosting a sense of national pride and identity.

In 1947, Maharajah Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo shot and killed the last three wild cheetahs in Madhya Pradesh. Five years later, the animal was declared extinct from India. In November 2020, the Indian government identified sites for reintroduction of the cheetah in the very state where the last cheetahs were shot. It was the upper echelons of Indian society that dictated the extinction, and yet again, it is the upper echelons that are orchestrating the return.

India has been trying to bring back the cheetah for more than a decade now. If cheetahs from abroad can be imported, so the logic goes, the species could thrive again on Indian soils as before. But academics like Ghazala Shahabuddin argue that the cheetah reintroduction plan is mired more in political symbolism than scientific rigor.

While talk of reintroducing cheetahs goes back to the 1950s, Jairam Ramesh, the then newly appointed minister for the environment, formalized a concrete plan only in 2009. When Iran, the only Asian country with an Asiatic cheetah population, declined to take part in the international endeavor, alternative cheetahs were found on the African continent. In 2012, however, the Supreme Court of India blocked the order due to concerns over introducing alien species.

In January 2020, the Supreme Court responded to a petition filed by National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and allowed the introduction of African cheetahs claiming that the word reintroduce had been erroneously used, as African cheetahs never inhabited India but they can still be introduced on an experimental basis.

The plan has been controversial from the start, eliciting widespread media coverage and passionate responses from conservationists on both sides of the debate. Conservationists against the policy say that this is a case of misplaced priorities; India needs to focus on the ever-growing list of other endangered animals. Others claim that bringing the cheetah back is the best way to protect threatened drylands. However, the discussion around the impact of politics on this plan has remained confined to academic circles.

Related on The Swaddle:

African Cheetahs Will Be Reintroduced to India 70 Years After Local Extinction

The prioritization of politics over science was clear when the cheetah reintroduction plan intersected with the lion relocation plan between Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. A section of the lion population confined to the Gir forest in Gujarat was supposed to move to Madhya Pradesh, in case the population was severely threatened by endemics or human-wildlife conflict. In 1990, the government selected the Kuno Palpur Wildlife Sanctuary in Madhya Pradesh for this translocation. To facilitate the move, 24 villages (nearly 5,000 people) were resettled, except the lions have not been moved even after an order from the Supreme Court of India. Gujarat has allegedly dragged its feet on the translocation due to a desire to maintain a monopoly over lion tourism.

The political tussle between the states and the lack of lions in the Kuno Palpur sanctuary led officials to select it as a potential site for cheetah reintroduction instead. Meanwhile, the lion population continues to be severely threatened as the translocation has not happened and no one has sought alternatives. The focus, it seems, has simply shifted to cheetahs.

The government’s inability to resolve this political impasse to protect lions poses questions about the precedence of politics over conservation. It is not far-fetched to think that similar problems might befall the cheetah reintroduction plan.

The very idea of cheetah reintroduction belies a heroic, political symbolism aimed at boosting a sense of national pride and identity. Shahabuddin highlights how such motives are driving the plan. Rhetoric like bringing back the ‘fastest cat in the world’ and India having 6 out of 8 big cats is used to justify the expense and scale of the project. The petition of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India to Supreme Court, 2014 states, “(Cheetah) is the only mammalian species to have gone extinct in peninsular India in historical times and bringing it back will have special significance for the national conservation ethic and ethos.”

The question then is: how is the cheetah uniquely positioned to meet national conservation ethics and ethos? Such fundamental questions remain unanswered, and the argument somehow circles back to how proud India would be to have the cheetah back and how groundbreaking the reintroduction would be. The due diligence that the government ought to be doing to invest in such a costly plan is largely inadequate. Many conservationists have voiced their opposition, citing concerns surrounding lack of prey base and adequate space for an animal that thrives in sizable grasslands as well as increasing human-wildlife conflict – which is a primary reason that India is losing its other big cats like leopards. The idea of having 6 out of 8 big cats might be alluring, but is not enough to justify the time and money investment.

Related on The Swaddle:

Habitat Loss, Climate Change Endangers 3 Wildcat Species Unique to South Asia

The cheetah reintroduction plan poses another question that lies at the heart of conservation: can conservation equally serve both the animals and those who live in proximity with animals? The plan would require another 169 villages to be displaced. Conservationists worry that villagers may face the same problems as the ones displaced for the lion relocation program, who suffered the loss of livelihood and impoverishment.

Academics have long argued for a more participatory view of nature conservation where local people’s knowledge is recognized and valued. Yet, the plan does not take local people into account other than resettling them. Biologist Ravi Chellam, while voicing his concerns to Shahabuddin, talked about the potential perils of introducing an unknown big cat without sufficiently creating awareness or involving locals in economic activities surrounding the cheetah. An exclusionary implementation of conservation policies can only prove to be harmful in the future, as locals are not empowered but actively oppressed to make space for animals.

If any big cats in India are to survive, then decisions need to be made in favour of animals and people. There is no glory in having all Asiatic cats if in 20 years, half of them do not survive. They are not Pokémon, India does not need to catch them all.

Sonakshi Srivastava is a writing fellow with Sentient Media where she focuses on the intersections between animals, politics, history, and culture. She has volunteered and worked with various animal welfare organizations in South Africa, Hong Kong, and Cambodia.

Related

In a First, Scientists Detect the Unique Markers and Benefits of Daydreams