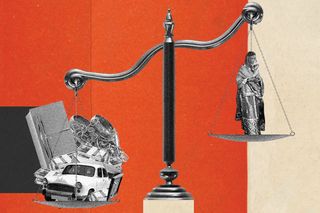

India’s Dowry Laws Are Ineffective, Easily Exploited, and Women Are Paying the Price

The misuse of dowry laws has led to an alarming number of innocent women getting caught up in the criminal justice system.

In India, 21 women die every day due to dowry-related violence. The cultural practice of dowry perpetuates the oppression, torture, and murder of countless women. The earliest laws to address the issue of dowry were passed in 1961. However, it is the 1983 statute – known as the “Anti Cruelty” statute or Section 498A of the IPC – which remains the most widely implemented, discussed, and controversial. The law was set up as a reactionary measure to immediately address the dowry problem and create distance between the victim and the alleged abusers. However, reactionary laws – often meant to appease the public – are rarely crafted after careful analysis of what is needed and what will actually work.

Several decades later, Section 498A remains extremely ineffective at addressing dowry-related crimes against women. Further, the misuse of the law has led to an alarming number of innocent women (and men) getting caught in the criminal justice system.

Understanding Section 498A

Section 498A criminalizes the act of cruelty toward a wife. Under the law, the offense of dowry harassment is cognizable, non-bailable, and non-compoundable. The law requires the victim’s testimony be taken as evidence entirely and gives power of arrest to the police at the request of the complainant. This means that no investigation or evidence is required prior to the arrest. Based on this flawed premise, Section 498A inevitably falls short on various fronts, with enormous consequences for those who get trapped by it.

Further, since dowry is embedded within the social fabric of India, the law fails on the fundamental basis upon which it was created: protecting women from dowry-related harassment, violence, and death. Since the inception of the laws, many people have been arrested; however, conviction rates have remained consistently low. In 2012, nearly 200,000 people were charged with dowry offenses, with only 15% of the accused convicted.

Wrongful incarceration of innocent women

In 2015 and 2017, I interviewed 85 women incarcerated in three prisons across India. The purpose of the study was to understand these women’s pre-prison lives, and what led them to be imprisoned. Among the women interviewed, 36 were serving time under Section 498A.

Speaking with these incarcerated women I started to see that most of them had little to nothing to do with the dowry crimes they were serving life sentences for.

Related on The Swaddle:

Marriage Is an Inherently Unfeminist Institution

Since a complaint under the law allows for immediate arrest and jailing of the accused (this includes the husband and his family members), there have been many cases where bed-ridden grandfathers and grandmothers of the husband, or sisters living abroad, or 2-month-old babies have also been arrested. Due to the way the laws are structured, all individuals accused (in most cases) receive the punishment of life imprisonment, regardless of the quality or quantity of their interaction with the victim.

The law fails to distinguish the nature of the relationship or physical proximity between the accused and the victim, which are crucial to determine whether or not the accused was actually involved in the harassment of the victim.

Neetu, for instance, is currently serving life for the death of her bhabhi, despite having met the victim only once at her brother’s wedding. Even though at the time of the incident she was at her in-laws home, she was accused and incarcerated along with the rest of her family. She emphasizes that since she only met the victim once and wasn’t present when her bhabhi died, it was extremely unfair for her to be serving the same amount of time as the rest of the family. The vague, over inclusive nature of Section 498A fails to consider these factors while handing out sentences for dowry related offenses.

Another inadequacy of the law is that it fails to consider how these women are embedded within their families. The role of women in India is tied to their family – a domain where they exercise little or no control. As researchers explain in a study of women in Hyderabad’s state prison: “A woman’s place in India is, in large part, defined by her relationship to the family, where her power and involvement in decision making can vary based on her age and whether she has a son.”

Consider the case of Jyoti, a 50-year-old woman who received life imprisonment for the death of her stepson’s second wife. She shares how she was threatened by her husband to help con four women into marrying her stepson. Jyoti, “I deserve life imprisonment. While I didn’t kill my stepson’s wife, I was forced by my husband into conning these women to marry my stepson. Karma was bound to catch up with me.”

We need to question how much choice Jyoti had in arranging the marriage and whether she played an active role when her stepson’s second wife succumbed to burn injuries. When looking at women’s offending, it is essential to consider how women’s limited roles in family structures inextricably links them to the offending perpetrated by their families. This limited agency inevitably limits their responsibility in the crime.

Misuse of the law

Owing to its premise of the case being based entirely on the victim’s testimony, there is the critical issue of the law being misused. With the rise of divorce rates in India, dowry laws have long been suspected for misuse by women aided by their lawyers to harass their husbands and relatives. In 2011, a trial court termed the misuse of provisions of dowry harassment by women as “legal terrorism.” Kamini Lau (an Additional Sessions Judge) stated, “The provisions of Section 498A are not a law to take revenge, seek recovery of dowry or to force a divorce but a penal provision to punish the wrongdoers. The victims (women) are often misguided into exaggerating the facts by adding those persons as accused who are unconnected with the harassment under a mistaken belief that by doing so they are making a strong case.”

So began a series of attempts to address the misuse of Section 498A. In 2014, the Supreme Court ordered the police to follow a nine-point checklist before arresting anyone on a dowry complaint. The court introduced this to avoid Section 498A from being misused as a weapon by “disgruntled wives” and for it to serve its main purpose of protecting women from dowry abuse and harassment. These changes stipulated that any individual accused would not be automatically subjected to arrest, there would be a prior investigation. This was met with strong opposition on the grounds that the victims of dowry harassment and their experiences had been ignored while deciding these changes. By introducing this nine-point checklist, the swiftness and immediacy of action from the police would be compromised.

Related on The Swaddle:

UN Report Spotlights Role of Family in Progress Toward Gender Equality

While the changes were not passed, the Supreme Court in 2017 passed a mandate in the Rajesh Sharma & Ors vs State of Uttar Pradesh & Anr case, requiring the formation of a family welfare committee in every district to investigate dowry harassment cases prior to arrest. This too was met with criticism from activists and scholars, who stated that the Supreme Court was virtually endorsing and legitimizing the stereotype that women exaggerate and fabricate stories of violence in order to seek revenge from their husband and his family.

In response, three judges led by the Chief Justice of India withdrew the 2017 directive that complaints under Section 498A of the IPC should be scrutinized by the Family Welfare Committee before legal action by the police. They acknowledged misuse of Section 498A and that there were inbuilt mechanisms in criminal procedure to check these misuses. However, no details were provided on these inbuilt mechanisms, providing us with no clarity on whether they actually exist.

Where does India go from here?

The law is not working; not only is it an inadequate measure to address the problem of dowry, its misuse leads to innocent people being arrested and incarcerated. Currently, the battle to prevent such misuse is being lobbied by Men’s Rights Activists, whose focus remains on the rights of men being violated. However, there are entire families that are potentially facing wrongful arrest and conviction. Fixing the law is a feminist issue. Changes to the law need to protect the rights of the victim and the accused.

With the introduction of investigation before arrest (recently proposed in the Maharashtra Police Manual), we can prevent misuse of the law and ensure that innocent people aren’t being swept up by law enforcement. To create space between victims and alleged abusers while investigations are being carried out, we need to provide separate housing and protection for the victims. Our laws can no longer be blind to the nature of the relationship between the victim and the alleged perpetrator (time spent together, physical proximity).

Other factors that have to be considered are whether women (mothers-in-law, sisters-in-law) exercised any agency when harassment and abuse did occur. These women’s lives and experiences need to be analyzed through the lens of how they are embedded in their families and that oftentimes their alleged offenses are not entirely of their own volition. By considering these factors when amending the current reactionary law, it is possible to change them without diluting their essence.

Ntasha Bhardwaj (she/her) is the founder of the South Asian Institute of Crime & Justice Studies and is a doctoral candidate at the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University. Her accomplishments include published papers on gender and crime and an IMDB page.

Related

In Lockdown Isolation, Children Have Become More Vulnerable to Online Predators, Watchdog Warns