Insects May Feel Pain Like Humans Do, Research Suggests

The discovery of pain perception in insects raises new ethical considerations.

We’re just starting to learn more about how insects perceive the world — and it turns out that they can feel more than what we previously believed. A new study, published last week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, suggests that the pain response mechanism among insects may work in a manner similar to that among mammals, including humans.

Although known to play a significant role in the ecosystem — helping in pollination, feeding off dead organisms and organic waste, and serving as the primary food for several other animals — and for exhibiting complex organisational skills, the response mechanism of insects towards pain has rarely been explored. As such, they have often been imagined as instinctive, as opposed to emotional creatures; and have also even been left out of animal welfare protections. Given that, the study raises new ethical questions about how we relate with insects and, consequently, co-exist with them. The researchers emphasize the need “to clarify whether we should be affording ethical protection to insects in potentially harm-inducing settings, such as farming and research.”

The study focuses on a process called nociception, which detects potentially or actually damaging events or stimuli in organisms. Nociception triggers a range of responses that serve as a warning to protect the recipient from harm — often, this is what we experience as the feeling of pain, a negative experience that the brain generates. Neurons from the brain execute and modulate this function in mammals, and this process is called descending nociception for the way it travels downward from the brain to the reflex organs via the spinal cord. The authors suggestthat insects also experience descending nociception — with the added ability to modulate the perception, just like in mammals. Almost all organisms display some sort of nociception, but the study shows how in insects, it can be similar to humans and other mammals despite the lack of a spinal cord.

Insects are wired to this process on three levels: molecular, behavioral, and anatomical. At a molecular level, insects can subdue reactions to damaging stimuli for both their central and peripheral nervous systems. Bumblebees are an example of this — they can suppress their usual avoidance of displeasing stimuli in the presence of a sugar solution. Behaviorally, insects may change their nocifensive behavior on the occurrence of changes to their brain. This was seen in the Drosophila, or the common fruit fly, which demonstrated marks of chronic pain in a 2019 experiment after one of its legs was removed. Anatomically, insects have descending neurons from the brain to the invertebrate equivalent of a spinal cord, which is responsible for carrying out nocifensive behavior.

These standalone occurrences among different insects may not point towards much in isolation, but when taken in consideration with each other they strongly seem to suggest that insects may indeed feel pain in a manner similar to how humans and other mammals experience it.

Related on The Swaddle:

Light Pollution From Street Lights Could Drive Insect Loss: Study

The commonalities between insects and humans in terms of pain perception have a few advantages. The authors of the study point out that further research into explaining the experience of pain among insects can lead to their use as model organisms for studying human pain conditions that stem from descending nociception.

The study also adds to growing evidence that insects are more sensitive than they seem. Pain is one aspect of this; previous findings have shown that flies can feel something akin to fear, fruitflies learn from their peers, and insects overall can exhibit pleasure, depression, even anger. Even Darwin observed how bees change their hum when they’re upset — and recent research confirmed that they also “scream” when alarmed.

The study comes at a crucial juncture of human history, when insects are being explored as a possible source of animal protein, and promoted as the “superfood of the future”. This is ostensibly to reduce our dependence on cattle farming, which remains one of the biggest contributors of climate change. With populations only projected to increase, the world is increasingly faced with the question of how to feed such a large number of humans while also not heating up the world any more. The Food and Agricultural Association of the United Nations has recommended farming and harvesting insects to meet this increasing demand.

However, these recommendations have been made on a possible assumption that insects do not feel pain the same way that mammals do. Pain and sentience have been important factors in the issue of animal farming: in 2021, the UK government came up with a new legislation that extended animal welfare protection to Crabs, Lobsters, and Octopuses, after arriving at the conclusion that these were highly sentient animals capable of experiencing pain. Octopuses particularly are known to be strikingly sharp and their intelligence levels match with humans. With this study, scientists suggest similar ethical considerations towards insects too. And it’s not just insect farming — ethical obligations should now be considered on many more fronts like laboratory testing or even in conservation, as the authors noted in a media release.

It also includes farming in terms of agriculture, where insecticides kill off untold numbers of insects every year. “All this research has some unsettling implications. At the moment, insects are among the most persecuted animals on the planet, routinely killed in almost-incomprehensibly large numbers,” notes Zaria Gorvett in the BBC. The European Union has already banned the use of pesticides that harm bees — this study, however, goes further in adding to the urgency to consider how we perceive the life of the little critters we share this planet with.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

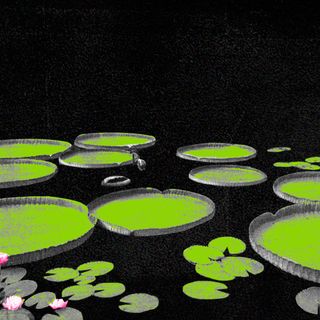

Scientists Identify the World’s Largest Waterlily Species That Was Hiding in Plain Sight for 177 Years