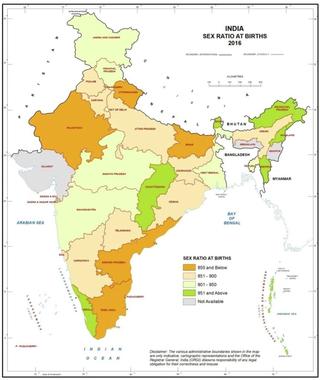

The southern states of India, with the exception of Kerala, have undergone a sharp decline in the reported number of girls born between 2007 and 2016 as compared to boys, according to a new census report titled “Vital Statistics of India Based on The Civil Registration System 2016” released by the Office of the Registrar General of India. Experts attribute the widening population inequality to poorly implemented laws and a harmful nonchalance on the part of government officials to investigate illegal practices.

India’s sex ratio at birth has been sharply skewed in favor of boys for a majority of the decade in question, with the overall figure for the country falling from 903 girls born per 1,000 boys in 2007 to 877 girls born per 1,000 boys in 2016, according to the report.

Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan, with the lowest sex ratio at birth, were recorded to have only 806 girls for every 1,000 boys born. Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have followed a similarly downward trend since 2007, dropping 108 and 95 points respectively, with Goa and Odisha following suit.

Image courtesy of the Office of the Registrar General of India

“The issue is that the economic worth of the girl child is not understood by the families and they consider her an economic burden,” Dr. Ranjana Kumari, director of the Centre for Social Research, said on Monday, adding that illegal sex determination to weed out girls is still a pervasive evil plaguing most communities — rural and urban. She offered up Haryana as an example of successful community outreach, the state that recovered from one of the worst sex at birth ratios and served as the launch site for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Beti Bachao Beti Padhao” initiative in 2015. Since 2007, the state has moved up in the index by five points, from a sex ratio at birth of 860 : 1,000 in 2007 to 865 : 1,000 in 2016.

Related on The Swaddle:

“There, it is improving because of more intensified work with the community, [through] mobilization and awareness programs,” Kumari said. “In Haryana, the image of the girl child — her freedom and her education — is changing.”

Haryana, Maharashtra, Punjab and Rajasthan are the only states that have successfully implemented the Pre-Conception and Prenatal Diagnostics Technique (PC-PNDT) Act, which bans sex determination to prevent sex-selective abortions, according to Dr. Neelam Singh, a gynecologist and chief functionary of the non-governmental organisation Vatsalya in Lucknow.

In the southern states, “it is either the unwillingness of the officers to enforce the act or their capacities are not up to the mark so they cannot do the [hospital] inspections,” Dr. Singh said of her visits down south.

In the east, however, most of the states had the highest sex ratios at birth in 2016, with Sikkim (999), Chhattisgarh (980), Nagaland (967), Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh (964) leading the charge. The eastern states, in addition to historically being less patriarchal than the rest of the country, have also witnessed immense success in literacy programs, which could be the reason for more equal girl and boy births, Dr. Singh said.

Other marked increases in the sex ratio at birth index include Delhi, where it jumped from 848 to 902 girls for every 1,000 boys, and Assam, where it increased from 834 to 888 girls for every 1,000 boys. In Kerala, which has had a mostly steady uphill climb since 2007, the sex ratio at birth increased by 10 points to 954.

The ideal ratio at birth should be 1,000 female to every 1,050 male children, according to the World Health Organisation. The unequal discrepancy arises because men are more likely to have a higher mortality rate in life than women, being more prone to earlier death by external causes such as accidents, according to WHO. Therefore, due to a slightly skewed sex at birth ratio, “the sex ratio for the total population is expected to equalize,” WHO says.

Related on The Swaddle:

Another obstacle in the way of reporting accurate sex ratios at birth is poor implementation of the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969. In states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, where birth registrations hover just above 60%, it is difficult to form a cohesive picture of the inequalities in the area. Private medical practices are to blame, in part, according to Dr. Singh. Due to illicit sex determination services being offered in private clinics across the country, medical professionals are less inclined to register births from their practice in fear of appearing to skew the ratio, she said.

“Technology has really exploited the mindsets of people. The problem has gone beyond medical professionals and gone to the quacks,” she said. “When we do not get the right demographic data, it definitely affects our planning for education and housing.”