Leprosy Bacteria Could Help Regenerate the Liver in Armadillos: Study

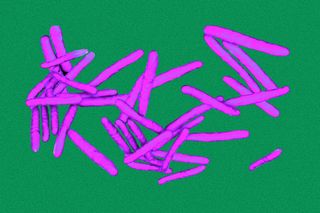

Bacteria responsible for the ancient disease of leprosy could potentially help reverse liver damage and regenerate this vital organ.

Parasites that cause one of the world’s oldest diseases, leprosy, have the ability to grow and regenerate livers in animals without causing any damage, scarring or tumors, according to new research.

“If we can identify how bacteria grow the liver as a functional organ without causing adverse effects in living animals, we may be able to translate that knowledge to develop safer therapeutic interventions to rejuvenate aging livers and to regenerate damaged tissues,” said the study’s author, Anura Rambukkana from the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Regenerative Medicine. This could even help reduce the need for transplantation that is currently the only treatment option available for those with end-stage scarred livers.

The liver is known to be the only internal organ that self-repairs. However, with time and repeated damage, it may slowly lose this ability, leading to chronic liver conditions. “Liver disease accounts for 2 million deaths per year,” the researchers noted in their paper. It is this regenerative ability of the liver that is “hijacked” by the leprosy bacteria, according to the research team.

Leprosy, also known as Hansens’s Disease, is an infection caused by parasitic bacteria Mycobacterium leprae that can cause damage to the skin, nerves, limbs, and eyes, if left untreated. It is an ancient disease that finds mention in the annals of history, but continues to persist today. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 127,000 cases were detected across the globe in 2020. A highly stigmatized disease, leprosy patients have faced historical ostracization and isolation. However, while it is infectious – believed to be transmitted through droplets from the nose and mouth – contracting the disease requires “continuous and close contact” with an infected person. 95% of those exposed to the bacteria do not contract the disease.

M. leprae is naturally found in armadillos and has the partial ability to reprogram cells. To study this further, scientists at the University of Edinburgh decided to infect armadillos with the parasite, comparing their livers with those of both uninfected armadillos as well as those animals resistant to the infection. Their findings, published in the journal Cell Reports Medicine, show that the infected armadillos developed enlarged livers that were healthy, unharmed, and fully functional. The livers had retained all the vital components such as blood vessels, bile ducts, and lobules present in the organs of the uninfected and resistant animals.

Related on The Swaddle:

Everything You Need to Know About Hepatitis C

They noticed that the bacteria, once it entered the body, head to the armadillo’s liver where it performed a “totally unexpected” reprogramming of the liver cells for its own purposes – a larger liver means there are more cells within which this bacteria can increase and proliferate. “It is kind of mind-blowing… How do they do that? There is no cell therapy that can do that,” Rambukkana told The BBC.

The team also believes that the bacteria reprogrammed the main liver cells, known as hepatocytes, in a way that turned back the organ’s developmental clock. The scientists noticed that hepatocytes in infected armadillos had reached a “rejuvenated stage.” These cells seemed to have returned to an earlier, younger stage of development during which they increase in number and grow new liver tissues.

“Livers of the infected armadillos also contained gene expression patterns – the blueprint for building a cell – similar to those in younger animals and human fetal livers,” noted the press release, adding that genes relating to “the anti-aging process”, specifically metabolism, growth and cell proliferation were activated, while the genes linked with aging were suppressed. This suggests that M. leprae “may have evolved to rejuvenate the adult liver,” the researchers wrote in their paper.

The bacteria’s ability to partially reprogram cells is consistent with the team’s previous findings. In 2013, the team had shown that the leprosy bacteria hijacks Schwann cells — associated with the peripheral nervous system — and reactivate developmental genes that return them to a previous stem-cell like state. They then migrate throughout the body, allowing the bacteria to subsequently infect more cells. Their recent study shows that the bacteria performs similarly in the case of liver cells. However, the exact mechanism remains unclear.

Noting the study’s limitations, Dr. Darius Widera of the University of Reading, who was not a part of the study, told The BBC that while the results could have positive implications for developing new therapeutic approaches to treat liver diseases, “[A]s the research has been done using armadillos as model animals, it is unclear if and how these promising results can translate to the biology of the human liver… Moreover, as the bacteria used in this study are disease-causing, substantial refinement of the methods would be required prior to clinical translation.”

But the recent discovery could still potentially pave the way for the future of regenerative medicine. Previous studies looking at regenerating damaged liver have done so by transplanting stem cells grown in laboratories into mice. However, this is an invasive procedure that often results in scarring and tumor growth, the researchers noted in a press release.

While further research is needed, the leprosy bacteria’s ability to grow livers without injury leaves hope of potentially harnessing this strategy in the future to regenerate and repair damaged tissues. As the researchers noted in their paper, the findings reveal that “regenerative medicine’s pursuit of a “grown-to-order” functional organ is not theoretical but has a naturally occurring precedent.”

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

How Autism Interventions Are Starting to Move Away From ‘Fixing’ Autistic People