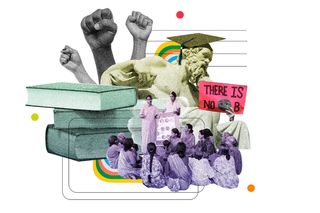

Liberal Arts Education Is Seen as ‘Less Than’ in India, but It Teaches the Skills India Desperately Needs

The multi-disciplinary model instills critical thinking and empathy, key skills in tackling climate change, economic, and gender inequality.

The German concept of bildung loosely translates as “education” or “formation” in English. But bildung is much more — it’s what shapes a whole person; the study of history, literature, languages, and the world, in general, helps cultivate a well-rounded outlook. The concept, which took shape in the 1800s, was encouraged, debated, and is considered one of the earliest bases of modern liberal arts education.

Today, the value of liberal arts education strikes out in its seemingly simplistic but versatile vision. Social cohesion and active citizenship become central planks of this learning process, promoting knowledge that is multi-faceted in its approach and allows one to engage with reality outside of one’s lived experiences. Especially when seen through the lens of the pandemic, and worsening sociological and ecological issues, this ideology seems too urgent to ignore.

The merits and limitations of such an academic model in the Indian context have been probed and prodded; it seems to pale in comparison to its better-touted half, STEM fields. The takeaways from STEM are deemed to be more ‘practical’ and tangible — the demand speaks to the need; as opposed to this, liberal arts seems an intellectual luxury at best and a waste of time at worst.

However, liberal arts signifies a core ideology, an approach to education that is democratic, unique, and responsive to individual choice. A standard curriculum looks something like this: a blend of history and ideology, conflict and identity, literature and world, philosophy, politics and society, climate studies, mathematics, and science, with add-ons depending on major/minors and individual tweaks. The choice to pick subjects and form unique combinations around them is the first push towards creative thinking, innovation, and problem-solving.

Key learning objectives of most universities include a notable academic rigor, multi-disciplinary approach for holistic understanding, focusing on breadth instead of depth, advancing critical thinking skills, and solving complex problems through perspective-building. “If you can read [Immanuel] Kant, write a paper, critique his writing, if you can do abstract algebra, game theory … you can do accounting,” Ashish Dhawan, co-founder of Ashoka University, said in a conversation with The Ken.

Such holistic education trains and equips students to view the interconnectedness of real-world problems, where the holy trifecta of systemic injustice, societal bias, and generational poverty hold the reins. A migrant crisis that affected more than 100 million people has as much to do with economic forces as with dignity of labor; any discourse around India’s manual scavenging problem must recognize caste and discrimination. The gender pay gap or lack of female representation in the workforce can be looked at from an economic, social, psychological, historical, or even scientific perspective. To understand why Dalits were disproportionately impacted during the pandemic, caste issues need to be dissected from social, economic, and cultural lenses. It might seem overly simplistic to say everything is interconnected, but social systems truly are.

Dr. Raghavan Rangarajan, dean of the Undergraduate College, Ahmedabad University, cited the following example: “In a studio (class) on water, students will learn to connect disciplines like biology, gender studies, and economics to find solutions to issues related to water.” Majoring in a liberal arts discipline is less about a degree, then, and more about a whole idea.

Related on The Swaddle:

This is a departure from India’s education system, modeled after the British, that promotes early specialization and professionalization. The system has been called “a sea of mediocrity” perhaps for the following reasons: findings of the Pratham Annual Status of Education (ASER) 2017 report conclude only 40% of our 14- to 18-year-olds can calculate the price of a shirt sold at a 10% discount; less than 60% can read the time from an analog clock. A recent study also showed that India’s STEM students fail to gain critical thinking skills in the first four years of education. “This is a serious problem because technologies change rapidly, and in order to be able to master new ones, you need not only a firm grasp of the subject area, but, above all, skills of the 21st century,” a press release said.

Another study by Mettle shows less than 5% of engineers have the analytical skills for software engineering jobs in product startups. Harvard University scholars William C. Kirby and Marjik C. van der Wende further argue that such a system insists on taking the human capital approach and leads to “a utilitarian focus on skills,” that vie for economic growth and competitiveness, “rather than on values focusing on social and political integration.”

In his book, The Fuzzy and the Techie, venture capitalist Scott Hartley points out the presumed binary between “fuzzies” and “techies.” If you majored in humanities and social science, you were a fuzzy, and if you majored in the computer sciences, you were a techie, he recounts. This binary has seeped into common thinking and comes with the implication that the latter is inherently superior, with people assuming that it’s the techies of the world who are primed to be leaders. Hartley disagrees: it’s the fuzzies who play the key roles in developing the most creative and successful new business ideas. “They are often the ones who understand the life issues that need solving and offer the best approaches for doing so. It is they who are bringing context to code, and ethics to algorithms. They also bring the management and communication skills, the soft skills that are so vital to spurring growth,” he argues in the book. Liberal arts education treats analytical skills, creative thinking, problem-solving, innovation, and critical thinking as the veritable end instead of being the means to an end, as it is these qualities that separate us from machines, that keep human contribution relevant. It is no wonder the World Economic Forum proclaimed these attributes as the “Top 10 skills of 2025.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Dissecting the NEP: How the Policy Will Only Widen the Education Gap in India

The multi-disciplinary setup primes liberal arts graduates to address social change and usher in social justice by being transformative in nature. It pushes against a theoretical approach and demands concepts be translated to practice. For instance, all programs involve some format of fieldwork or ground project for which students design a solution to address a pervasive social problem, be it education, gender, agriculture, climate, or myriad other things. One such fellowship identifies its agenda as to “think critically, communicate effectively, collaborate meaningfully, and become leaders with a commitment to public service.” Another notes that it is “designed to get students to recognize the socio-economic ground realities of India.” The familiarity with social challenges succeeds in achieving two things: embedding compassion and promoting a ‘ground-up’ approach that prioritizes social justice challenges rather than a ‘top-down’ one. “It is this that prepares us for leading a meaningful life, not just the next job,” says Maude S. Mandel, the president of Williams College, the U.S.’s top-ranked liberal arts college.

The academic makeup is also proactive in addressing issues the future generation will face. The climate crisis, arguably one of the most urgent considerations of our time, is a good example. Traditional curricula carry insincere modules about environmental science and preach sundry ways like carpooling — which fail to relay the extent of an issue that displaced over 10 million people globally in the last six months itself. Closer to home, around, 2.7 million Indians were affected in 2019 due to climate change-related disruptions. On the other hand, addressing climate change as part of specialized Master’s courses ends up saturating knowledge amongst a small group of people. In comparison, this is the description of a liberal arts module on climate for undergraduate students: “Any environmental issue is invariably about society and politics. From global warming to garbage on city streets, nature and culture lie at the center of competing claims about what should be done.… This course looks at how biophysical processes in natural landscapes are changed by the cultural geography of capitalism, colonialism, caste, and nationalism.”

Of course, even liberal arts education has its follies. The structural institutions built around liberal arts need to shed the elitist tag, become more accessible, and grow in socioeconomic diversity. The current discourse around academic freedom and Ashoka University’s intelligentsia further betrays the fickleness of private universities. But the inherent value of providing such holistic education within flexible models is undeniable. Thus, although a liberal arts degree in a private university might not be accessible to all, perhaps students and society can benefit from adopting the models provided by different courses.

If applied effectively, a liberal arts education can shape urgent, considerate answers to dynamic questions, contributing to development. The pandemic spotlighted a lopsided social system rigged in favor of those in social, economic, and cultural power. Humanist values of social welfare and dignity, which are the aim of a well-rounded education, are key for a path that leads to recovery and inclusivity. The understanding of what it means to be human, argues Ross Wilson, the director of liberal arts at the University of Nottingham, in the U.K., can enable anyone to assist in innovating and changing the world. The future needs empathy and social impact, both of which can be fostered in an academic model that prioritizes social justice.

French Renaissance philosopher Montaigne argued that such an education would usher in a process where beliefs and values are challenged and aspects of self are discovered and nurtured in order to become “wiser and better” for the society. He said, “Let us begin with the art that liberates us.”

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Pass It On: At Work, Caring About How You Present Yourself Is Not The Same As Being Inauthentic