Many Muslim Women in India Face Discrimination During Hiring Process, Shows New Research

“Most diversity and inclusion initiatives focus on increasing women’s participation with limited attention to [the] intersectionality of religious and ethnic minorities,”

Between Priyanka and Habiba, two women of equal caliber, who would you hire?This was the central thesis of a recent experiment, conducted with the aim of detailing the level of discrimination Muslim women face in the Indian workforce. The findings indicated a trend that people have been familiar with anecdotally: a Muslim woman is half as likely to get a call-back in an entry-level job as compared to a Hindu woman — even if they are equally competent.

The study, carried out by LedBy Foundation, was published last week. “Most diversity and inclusion initiatives focus on increasing women’s participation with limited attention to [the] intersectionality of religious and ethnic minorities,” the researchers concluded.

The context of the study is indeed grim. According to the report, India has close to 50 million women from Muslim communities who are of working age. Yet, their representation in actual numbers is almost invisible: only 10% of the women in the workforce account for Muslim women, according to the 2011 census.

To show just how much the bias prevails, the researchers conducted a real-life experiment to account for modern-day variables. They created two resumes — one for “Priyanka,” a typically Hindu name,” and one for “Habiba.” Both Priyanka and Habiba had comparable achievements and none was better than the other. Out of the 1,000 entry-level job opportunities that the two profiles were submitted to, Habiba’s profile was favored in less than 50% of opportunities, even though the resumes were identical. “Priyanka received 120 responses from unique organizations while Habiba received only 15,” the study showed, signaling a “massive discrepancy for call-backs for Muslim and Hindu women, proving a significant hiring bias against Muslim women.”

Related on The Swaddle:

How Schools, Colleges Socialize Indians Into Perpetuating Islamophobia

This pattern was echoed across industries — everything from e-commerce, e-learning, and information technology to marketing and advertising. Moreover, the bias against Muslim women was most prominently recorded in North Indian states.

A history of work would be incomplete without accounting for an unshakable gender gap, one that has widened more during the pandemic. For decades, women have struggled to access equal opportunities and pay, with most workplaces perpetuating some form of gender bias knowingly or unconsciously. In India itself, one report shows that women are paid 34% less than their male peers.

The short and long of it is that gender continues to be a barrier. What the new research points out is the discrimination that plays out due to intersectional identities. Women, and Muslim women, in particular, face a bias that stems from religious, caste, class, and gender anxieties.

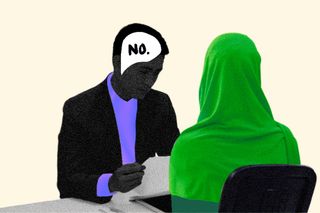

Previous reports have explored the discrimination Muslim women face by virtue of their appearance too. Wearing hijab ruffles up much cultural anxiety in a country in the cold, vitriolic grip of Islamophobia. Hijab-clad women are often discriminated against for exercising their personal choice as a result; their display of faith is interpreted as something “suspicious” and “out of place” in the corporate world. “It [society] makes me feel I am different,” one such woman told The Wire. “People from other religions who wear visible religious symbols are not questioned. Sikh men, for example, wear turbans and so do a certain section of Sikh women. Hindus wear tilaks if they want to. But they are not asked to remove their religious symbols before they come to the office.”

The findings of the LedBy study are similar to another survey conducted in 2017. Harvard Business Review researchers examined the bias against Muslim women in German society, showing the discrepancy in how the job market reacted to women who wear hijabs as to women who don’t. Even there, employers were more likely to hire women who didn’t wear a hijab — for it showed their willingness to “integrate” into a “secular” environment.

Related on The Swaddle:

‘Brilliance’ Bias Favoring Men Over Women Affects Gender Parity At Workplaces

The gatekeeping in professional areas run parallel to a culture of hate and violence against India’s Muslim community. Over the last six months in itself, Muslim women have faced abuse online (when their pictures were auctioned), in the education space, and in rallies and protests. The work culture is not divorced from this ideological and physical violence. Then, the conversation around gender inclusion at work must account for intersectional identities that are so often sidelined — and forgotten.

For all the trumpets blown in the name of “diversity and inclusion” initiatives by companies, there is a need to retrospect and scrutinize their impact. The researchers suggest not only expanding the scope of D&I opportunities, but also setting a panel that constitutes people from different social, economic, and ethnic backgrounds. “[This] can help mitigate personal unconscious biases and consider an applicant from a broader perspective to make a more informed decision,” the study notes.

More importantly, however, is the need to instill a process of “name blindness” while hiring. The politics of naming spill into workplace discrimination for other marginalized groups too; both first name and surname are strongly tied to one’s social identity, and are used to uphold a fractured status quo. For instance, a reportpresented by the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry showed that over 90% of Indian surnames reveal people’s caste, furthering system discrimination. Names, in their explicit and implicit power, trigger a cycle of judgment — those that hint at a marginalized background (either by virtue of their gender, caste, or religion) are perceived to be less competent than those coming from “affluent” social backgrounds.

The systemic injustice that existed by way of lack of opportunities then gets a new lease on life; it further restricts access to security and wealth for people. For good reason, the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry recommended hiding candidates’ surnames in the Indian Civil Service examination.

Stripping an application of name, age, and background can be a deliberate action against bias that so perniciously seeps in at an early stage. Negating name from the hiring conversation is only the start; acknowledging the rot is the only way to truly address what happens after this stage.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

In Conversation: On the Indian Couple Who Was Thrashed for Public Kissing