Menstrual Cup Companies Struggle to Go Mainstream in India

While the Indian market slowly embraces menstrual cups, health regulation and access problems still make it a niche choice.

In June 2018, BuzzFeed India released a video about women’s first experiences with sustainable period products like menstrual cups and cloth pads. This was when I first stumbled upon the idea of a menstrual cup. As per my Instagram feed, I wasn’t alone in discovering the cup, despite my privileged background. According to Suparnaa Chadda, founder of gender equality initiative Women Endangered, even people from the medical community are unaware of menstrual cups.

That’s not for lack of effort by India’s small but growing menstrual cup industry.

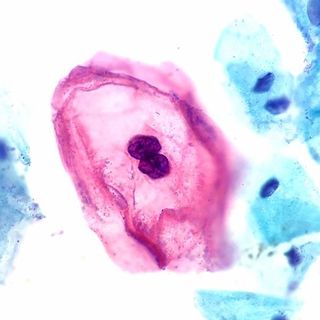

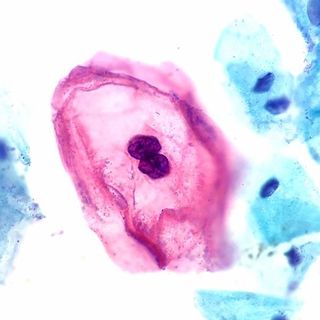

A menstrual cup is a reusable cup-shaped piece of medical-grade silicone that is inserted into the vagina in order to collect menstrual blood. It is emptied and washed at regular intervals during a person’s period. The cup is slowly growing in popularity in the West, garnering a following for its long-term reusability, which reduces menstrual waste and its harmful impact on the environment. But the nature of the product — that it would last a customer a minimum of 10 years — does not attract the attention of general retailers in India, like the average chemist shop.

Pads are fast-moving consumer goods — products that are sold frequently and at relatively low cost, ensuring a steady pipeline of profit for companies that sell them. Their disposable nature makes pads fast-moving products that bring customers back to the store regularly for more. A menstrual cup, on the other hand, sells more slowly — it is not easily disposable and lasts for years; therefore, it doesn’t bring customers back for more.

But even niche retailers struggle to add menstrual cups to their inventory. In our conversation, Priyanka Jain, co-founder of the menstrual product manufacturer and retailer Hygiene and You, mentioned that local and international manufacturers often demand she order one lakh pieces per month, which is unrealistic for her as a seller. “I am not Whisper Ultra that I am going to sell so many pieces [every month],” she said.

Related on The Swaddle:

From Riches to Rags: The Evolution of Menstrual Taboos in India

While the nature of the menstrual cup won’t change, greater demand from consumers could allow retailers, both niche and general, to stock more. But in a patriarchal culture that values virginity, the fact that the cup has to be inserted into the vagina makes people hesitant to use it. Even when people are interested, a cup is not always an affordable product, as compared to a pad. Since a lot of cup sellers currently import their products, the average cost of a menstrual cup is close to Rs. 1000. While more cost-effective in the long term, for many people, the upfront cost is not as possible as purchasing packets of pads that cost only Rs. 40 to 300.

Local manufacturing would bring down the cost of menstrual cups, but manufacturers would still have to contend with gaining consumer trust in a cheaper product.

As of 2018, the Bureau of Indian Standards was in the process of devising standards for reusable feminine hygiene products like cloth pads, labia pads, and menstrual cups. Though menstrual cups can be sold, there are still no safety regulations in place for their production.

Dr. Simi Sugathan, the founder of the Safety Monitor Research Foundation (SMRF), a consumer product rating organization, said there is no uniformity in the manufacturing process for menstrual cups. “So one brand can manufacture the cup in a presumably safer way compared to another brand manufacturing the cup under unhygienic conditions. However, a layman will not be able to find out the difference between those two,” she explained.

In the absence of state regulation, SMRF has devised a set of guidelines and certification program based on European and Australian regulations for the manufacturing and selling of menstrual cups. However, participation in the verification process is voluntary, and its thoroughness is offputting for manufacturers; Hygiene and You was the only brand interviewed that chose to share some details about its manufacturing process and general safety standards with SMRF. According to Dr. Sugathan, many cup manufacturers don’t participate at all. (Boondh, a menstrual product social enterprise that also sells its own branded cup, which is manufactured in Chian, received its quality check from U.S. Pharmacopoeia, a U.S. non-profit quality standards commission, and the U.S Food and Drugs Administration. SheCup, an Indian cup manufacturer, received its quality test from U.S. Pharmacopoeia, as well.)

In fact, there is a larger need for improvement in how feminine hygiene products are manufactured and sold in India, Dr. Sugathan said. Cup manufacturers interviewed point out that sanitary napkin brands do not disclose the constituents of their pads on the packet. While the BIS statute for sanitary napkins is currently under revision, the standards have previously only been concerned with the dimensions, disposability, pH value and absorbency of the pads — not the ingredients.

Related on The Swaddle:

Tampons to Sponges, A Round‑up of Menstrual Options

But the need to regulate menstrual cups is most urgent, Dr. Sugathan said. “The cups are a much more serious device than the sanitary napkins. You insert the cup in your body for 12 hours at a stretch, a minimum of four days a month. Whereas the napkins, even with prolonged hours of use, are always kept outside of the body. The potential risk of napkins remains lower than that of the cup,” she said.

Manufacturers and retailers interviewed are actively engaging with customers via menstrual health management programs to build awareness and acceptance of their products. Despite the limitations on how cup products can be sold and bought, there’s still a market for it, they said — both among people who are used to homemade methods (e.g., old rags, hay, and dried leaves) of management and need more hygienic options, and among people who already use period products regularly, but might be interested in a more reusable, environmentally friendly method, said Hygiene and You’s Jain.

There has been some improvement in the penetration of menstrual cups in the last few years. Manish Malani, the co-founder of SheCup, said the company’s sales have reached 300 to 500 pieces a month, due to a new digital marketing strategy that involved selling on and upgrading the company’s online payment gateway in collaboration with Amazon. They also invested in Google and Facebook advertisements.

Yet, there’s still a long way to go before menstrual cups in India are sold as over-the-counter products at chemists and general retail shops. A common theme among people working in the menstrual health industry — manufacturers, risk assessors, and promoters — is the need for people to be able to make an informed choice about their preferred menstrual product. For that to happen, there needs to be a larger shift in the discourse towards period positivity and body positivity, beyond an increase in the accessibility of products like pads and menstrual cups. After all, as Jain said, the “product is not equal to empowerment.

Bhanvi Satija is a feminist journalist based in New Delhi. She cares and writes about all things gender and education.

Related

Would Women Trust Men With the Sole Burden of Contraception?