A Therapist’s Notes on the Mental Health Fallout of the CAA‑NRC Protests

“The country is burning,” A.R. sat in front me with her face buried in her hands as she cried.

Editor’s note: The author has received permission from each of her clients to share details of their stories.

Since mid-December 2019, the concerns of clients coming to me for therapy have changed. Conversations have moved from “I” to “India” and focused on the repercussions of recent political decisions, such as the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Registry of Citizens. Clients now schedule their therapy appointments based on protests timings, and clients now come to their sessions either emotionally charged or absolutely exhausted. Our political climate forms the backbone of our sense of security, stability, and belonging, but current events have triggered a mixed bag of emotions within clients that include fear, rage, insecurity, and confusion. This has disturbed the basic foundation of mental health.

N.C. works as a consultant and although she was always abreast of world affairs, she never felt passionately enough about any issue to have a political opinion about it, let alone do something about it. But the CAA, in her words, took over her brain and “everything else seemed trivial.” N.C.’s colleagues thought it would be good for her to seek help when she started having emotional outbursts at work.

To me, she complained of being unable to focus at work. She said there was so much information about CAA-NRC protests floating around that even if she tried to block it out, she couldn’t – and she wasn’t even sure if she wanted to. She went from being someone who enjoyed her work, to now struggling to form a connection with her work. As she stood there among the protestors on Carter Road, Mumbai, she found something new she could connect with — her country – it gave her a sense of hope. She found a community that shared a similar ideal, and this made her feel connected to a cause greater than herself. She felt as if she was “taken back to history textbooks,” wondering if this is how “freedom fighters felt.” However, this came at a high price. Her productivity, ability to focus at work and be an active participant in work-related discussions took a beating — all she could think about was the political climate.

S.M. was always irregular with therapy, even though he suffers from severe depression, but had been doing better over the past few months. Recently, he sat in front of me in therapy and retold a conversation he had had with his mother the previous night. Before she went to sleep, she asked her 19-year-old son what is going to happen to them as Christian minorities in India – ‘will they be kicked out of their homes,’ or ‘should they start packing and plan to leave the country.’ After this conversation, his nights were spent sleepless; he paced around his living room thinking of what he would say to pro-CAA protestors, and should he interact with them. The intense fear has now caused him to now be “protest ready” — he goes about his day with protest signs and a few extra to pass around.

Related on The Swaddle:

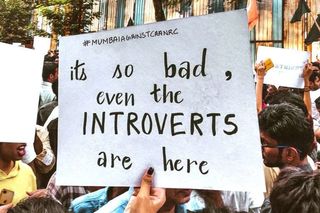

How Anti‑NRC‑CAA Humor Can Work as a Tool of Political Resistance

Like N.C., S.M. too, has started to constantly consume copious information regarding the CAA. They both find it difficult to disconnect and disengage from it, leaving them over-stimulated and unable to function in their regular routines. In therapy for both, we divided the day into parts focused on professional growth, down-time, and media consumption. This clear cut time allocation allowed them to be more productive. We intentionally left media consumption for the second half of the day because what they consumed triggered them the most. We chose a dedicated time, recognizing the importance of maintaining a balance between being functional at work and staying afloat during the current political crisis in the country. The second half allowed them to begin their day with focus and gave them enough time to wind down from media consumption at night, thereby ensuring their sleep was undisturbed. We also worked on a sleep routine that involved activities that would allow them to disengage and rest, such as a warm shower, a workout and reading a fictional book.

“The country is burning.” A.R. sat in front of me with her face buried in her hands as she cried. She had come in for therapy a few days earlier than her scheduled bi-monthly appointment. She had spent the last ten years pursuing her academic interests overseas. She returned over a year ago because she wanted to feel ‘at home’ only to discover that “this place definitely did not feel like the home” she grew up in. Her political opinions differed from her parents’ opinions, and they were increasingly becoming averse to the idea of listening to her whenever disagreements arose. This was a stark change from her parents who were usually open to all conversations. For A.R., these were not regular disagreements but represented something larger — “living in echo chambers, where the freedom of difference is no longer allowed,” she told me. The constant disagreement with her parents made A.R. feel that her freedom of thought was being violated. Her parents believed their pro-CAA beliefs were “right” as they feared a previously corrupt ruling party coming to power, and thus offered complete loyalty to the currently ruling party as the only way to protect themselves.

A.R. and I discussed the concept of freedom.For her, it meant the ability to think, express and be herself. This included the ability to consume more information and not have that filtered down for her through people’s biases. It included the ability to question things and to not blindly follow other people’s perspectives. During our conversations, we realized that it is not only important for us to learn ways to express our freedom but also do so while respecting others’. We went through empathy techniques such as listening, summarising and ensuring we have understood another person’s opinion/perspective before expressing our own thoughts. We created a set of guidelines for her home, that we hoped her family would follow such as politics-free-zones (the dining table, bedrooms or car rides) and worked on ways we could politely keep the tone and volume of any disagreement in check. The evolution of thought begins with disagreement and we must be open to it. However, this is difficult, especially within families, and must be encouraged in environments that are respectful, where all participants are willing to listen and not overrule the other.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the NRC‑CAA Will Affect Women, Transgender People and People With Disabilities

N.M. is an older Muslim male client of mine. For most profiles, this detail would be irrelevant, but today it is not. His recent visits to me were because his “worst fear came true” — the fear of being judged and shunned for being Muslim in his own country. When the current ruling party got voted in for the second time last year, this fear took definite shape; the party’s continuing lockdown in India’s only Muslim-majority state of Kashmir strengthened that fear. N.M. now fears he will be displaced from his home because of his religious beliefs under the new citizenship rules.

To fight for his home, he finds himself at protests post-work hours; he made it a point to stay at the Gateway of India protest till 5 a.m. and then go to work. But, he does not update any of his social media platforms with his political views or his experience at the protests because he fears being discriminated against by his friends and work colleagues. He even chooses to stay silent at work and often avoids eating meals with his co-workers, fearing they will ask him for his political opinion, which he believes won’t be accepted. Additionally, apart from the physical fatigue of regularly going for protests along with attending office, he is emotionally fatigued (an accumulation of stress-causing feelings of tiredness, and being overwhelmed). The emotional fatigue is a result of the constant outbreaks in the country — every time he feels they have won a small victory, he wakes up to another grim piece of news regarding the CAA, making him feel helpless, hopeless, lethargic and despondent. This makes it excessively difficult for him to be functional, let alone productive, at work. Even though N.M. is aware this is a long fight, he often questions if the only thing the future has in store for him is “doom.”

Through therapy, N.M. has gradually found the strength to step out of his comfort zone. He and I worked on reaching out to people and actively engaging in a healthy dialogue with them. Now, he has created a small circle of friends from different backgrounds and political views. This group includes his childhood friends and some people he met at protests, whom he feels he can trust without fear of discrimination. He meets them regularly and shares his views, thereby creating a safe space to be and express. Besides the non-judgmental community the group provides, it also helps N.M. think aloud and find a deeper sense of belonging to his country and fellow citizens. In therapy, we also worked on his feelings of “greater doom” and hopelessness. With the recognition that this battle is a marathon, I worked with N.M. on finding hope — by celebrating small victories, such as his resilience and that of protestors to continue to occupy Gateway of India, even in the face of worsening conditions around them. These victories help prevent him from feeling overwhelmed by setbacks and help him focus on the positive now in his journey. Paying attention to others’ resilience, for instance, has slowly inculcated the belief in N.M. that perhaps the government will indeed have to pause and listen to them.

Our basic response to fear is to either flight or fight, and the theme of most of my interactions is that young India is choosing to fight for true democracy and the safety of their home. They believe political decisions are now threatening their basic need for safety and thus they feel it is their responsibility to protect it. Their weapon is education; the willingness to hear a different opinion and ability to express their opinion without being shut downis what keeps them fighting. Even though this dialogue may cause feelings of anxiety, it has not deterred most but added to their willingness to stick to it. If anything, this movement can be summed into “anxious resilience.”

Priyanka Varma is a clinical psychologist, counselor, and psychotherapist. She currently consults at The Thought Co., Holy Family Hospital, and Global Hospitals.

Related

Why Indian Women Protesters Sang a Chilean Anti‑Rape Anthem