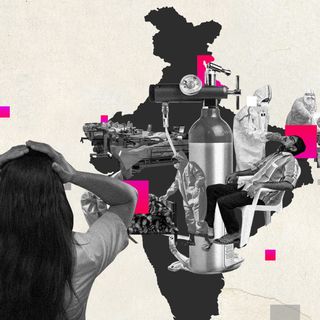

Mental Illness Is a Common Comorbidity of Tropical Disease. How Can India’s Healthcare System Treat Both?

Training auxiliary healthcare workers to treat common mental disorders like depression and anxiety is a cost-effective way to help patients immediately.

This is the final report in a four-part series that explores the social determinants of living with and in proximity to lymphatic filariasis, a neglected tropical disease.

“I keep thinking about what might happen if my swelling doesn’t go away,” says Aarti Pal, 37, from Rae Bareli district in Uttar Pradesh. When asked to elaborate on what she thinks might happen, Aarti smiles a bit and reiterates, “I just keep thinking about what might happen.”

Aarti is a housewife who has lived with lymphatic filariasis (filaria) on her arm for a few months. She says she’s fine — her medication helps reduce fever, she’s only occasionally tired, and her swelling isn’t extreme. Her kids are loving; they make sure she takes her medication and care for her.

And yet, the small voice in her head has persisted for the few months she’s lived with the swelling — what might happen if this doesn’t go away?

Aarti Pal. Photos by Sunny Singh

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), lymphatic filariasis is the second most common cause of long-term disability, with the first being mental illness. However, mental illness, especially depression, is a well-known comorbidity of lymphatic filariasis due to the long-term disability caused by lymphedema (swelling of the limbs) or hydrocele (swelling of the scrotum). One in two people with filaria experience depression or anxiety, according to the WHO. The mental burden of living with a neglected tropical disease can manifest as severe mental, neurological or social problems, or it can lead to substance abuse and self-harm as a means to cope.

Filaria affects an individual’s mental health because of stigma and disability. Though preventative and care-based treatment for filaria are free in India, there’s no similar treatment offered for mental illnesses caused due to filaria. In this case, ignoring a significant comorbidity is only treating half the problem.

In India, talking about and seeking help for mental illness is heavily stigmatized, especially in semi-urban and rural parts of the country. But, people with filaria deny facing any stigma. People are lovely, caring and tend to help each other, the patients say. However, Dr. Ritu Shrivastava, a district malaria officer in Rae Bareli, who often works with filaria patients, disagrees.

“It is nice that they say there’s no stigma, but it does exist. Patients with filaria are identified in society with specific names — the lady who has a swollen leg. Or maybe they aren’t invited to some functions, or public gatherings because they won’t be able to walk. This does leave an emotional and mental impact on the person with filaria. Society may not do it in a blatant manner, but the subtle stigma does affect patients. They may not think too much of it, because they could be focused on their own thoughts about their treatment, or they may even be in denial. But, there is a stigma.”

This stigma is also heavily gendered, with women facing more ostracization by their community and family, as compared to men. As The Swaddle has reported previously, women are often deserted by their partners when they show visible signs of disability due to filaria. Women with filaria also cope with severe low self-esteem when their disability prevents them from taking care of the family or getting married.

Related on The Swaddle:

Know Your Rights: Disability Laws in India

This degree of stigmatization, according to a review of the community impact of filaria, is directly correlated to the severity and visibility of the swelling. Rajeshwari, 65, from Rae Bareli, who has lived with filaria for around seven years, says that she remembers the first time her neighbour’s leg started swelling. “It was so bad…they could barely walk. I kept thinking, what would happen to me if this happened to my leg too?”

When it did, Rajeshwari’s major concern wasn’t stigma from neighbours. She said, “The most stress I face is when I’m unable to complete my daily work. I get in the morning and I have to sit down after making 2-3 rotis because my leg hurts so much. This works out because I only have a few people to feed, but I’m always stressed because I can’t find anyone to help me out.”

Rajeshwari. Photos by Sunny Singh

The inability to keep up with work — both household and employment based — is a well-known cause of mental distress for individuals, with research stating that it leads to a drop in self-confidence. Disability, poverty, and lack of opportunity creates a vicious cycle that can make individuals vulnerable to mental illnesses, which then affect their ability to take care of themselves and follow treatment protocols.

Related on The Swaddle:

What It’s Like to Live With: Physical Disability in the Times of Covid19

The solution is to create a solid rural mental healthcare system that is easily accessible, affordable, and helps dispel stigma and aid community support for those who live with filaria. As of now, India’s rural mental healthcare system may as well not exist, due to the severe lack of trained mental health professionals — especially psychiatrists — in India.

“Rural and tribal populations have to travel several kilometres to access mental health care facilities, which is a big challenge. People tend to live with mental health concerns/ignore symptoms, as they find it challenging to travel this much. They also lack awareness on what constitutes mental illness, and that they have to access mental health care facilities for ill health.” says Dr. Asha Banu Soletti, a professor at the Centre for Health and Mental Health at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. “The effective implementation of district mental health programmes to correct the lack of mental health training provided to general practitioners in primary health care centers can bring changes in the lives of people living in tribal and rural areas.”

Research shows that the most cost-effective way to add mental health interventions to rural and semi-urban spaces is to use lay healthcare workers (a member of the community who has received some training to carry out healthcare services) to help treat common mental disorders like depression and anxiety — which are very common among those who live with filaria. Further a randomized, controlled trial in Goa, India, showed counselors in public primary care facilities helped people recover better from common mental disorders.

Until the implementation of such interventions becomes commonplace in rural and semi-urban India, the joint burden of living with disability and mental illness is a silent one for those who have filaria. Individuals like Rajeshwari will know to articulate the struggles they face when it comes to everyday life, but may never know how these struggles impact them emotionally.

When asked about her mental health, Rajeshwari’s face becomes stoic. She says, “You have to live with what life throws at you.” Then, she changes the subject to how well her children are doing and how that makes her happy. “Everything is fantastic.”

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

Indians Living Abroad Are Feeling Grief, Despair. Many Are Using The Internet to Help.