#MeToo Is Taking Down Predators. But Innocent Parties Are Going Down With Them.

Small-fry projects and colleagues struggle to shake off guilt-by-association.

#MeToo has made us, as a society, contend with many uncomfortable realizations – the importance of believing survivors of sexual harassment and assault, even if they choose to remain anonymous; and holding bystanders accountable if they stayed silent while observing predatory behavior, since this is complicity. But even as we settle into these tense realizations, we’re now presented with a third: disengaging with predatory men can affect innocent, third parties. When a movement to empower one group of women threatens to disempower another, can it be called a success?

Filmmaker Shazia Iqbal’s open letter to the MAMI Mumbai Film Festival board, in which she questions its integrity and decision-making in its attempt to clean house in the wake of #MeToo, can be credited for bringing this question to the forefront of conversations around the movement.

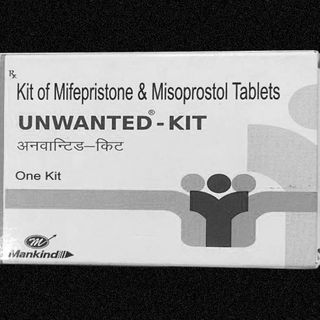

Iqbal penned her now-viral open letter on 19 October, after MAMI dropped five films that were produced by men who had been accused of sexual harassment, or men who were perceived as complicit in that harassment. Iqbal’s film, Bebaak, produced by Vikas Bhal‘s partner Anurag Kashyap, was one of these.

“In the rush to ostracize anyone remotely connected to the accused, we cannot be trampling over the livelihoods of those who are innocent. Does our work not matter at all?”

“I was called and told that my movie was dropped from the festival — no reasons given, no official communication sent. I wrote to MAMI repeatedly asking the board to at least give me an email detailing their logic. I wrote the open letter when I didn’t hear from them for almost a week,” says Iqbal.

Ironically, Bebaak is a film with a strong feminist storyline, and more than 50% of the cast and crew of the film is female. This is no mean feat, given that research as recent as 2016 by Oak Foundation and FICCI Ladies Organisation shows that men outnumber women by a ratio of six to one in India’s film industry, while male directors outnumber female ones by a ratio of nine to one.

Worse, while MAMI had dropped some films from its screening lineup, using, ostensibly, the guilty-by-association logic, other films — bigger ones that should also have been dropped if association was a crime — were kept on by the board. For all intents and purposes, the smaller fish had been hung out to dry, while the bigger fish were still enjoying institutional protection.

“Unofficially, some important members reached out to tell me that they, too, felt the decision was unfair, but their hands were tied,” says Iqbal. “My stand was simple — either they drop all the films and people that were associated with ‘problem’ names, or they allow all the movies to be screened. But they were never going to drop important names like Lars Von Trier, Paul Schrader, Nagraj Manjule, and others. Only the smaller films were forced to suffer.”

While it was only a matter of time before heads started rolling, given the avalanche of accusations under #MeToo that have swept many industries — most prominently the media — it is by no means just the aggressors who now find their careers on shaky ground. When anonymous accusations of sexual violations surfaced on Twitter against CEO Kartik Iyer, Managing Director Praveen Das, and Senior Creative Director, Bodhisatwa Dasgupta, of Bengaluru-based advertising agency, Happy Creative Services, all three men were forced to step down. Despite their departures, uncertainty and insecurity still lurks the corridors of the agency’s offices.

A female employee, on condition of anonymity, says, “All three were first-rate creeps, and it’s a relief they’re no longer around, but I didn’t expect that there would be so much chaos — maybe I was naive. I hear rumors about clients that might be leaving because they don’t want to be associated with us anymore. Why should the rest of the team be punished? Those three have enough money already, it’s us who have to live with the fear that if too much business goes away, we might not have a job. It’s so unfair.”

A female member of the crew of Netflix’s Sacred Games, who requested anonymity, says, “In the rush to ostracize anyone remotely connected to the accused, we cannot be trampling over the livelihoods of those who are innocent. I’m glad that the inquiry cleared Varun Grover, and that Netflix decided to continue working with Anurag [Kashyap] and Vikramaditya [Motwane], but I don’t even know why it was a question that the show should be cancelled. It’s a slap in the face of everyone else who poured their sweat and blood into the show. Does our work not matter at all?”

While on one side of the fence are all the people who, justifiably, shouldn’t be punished for the sins of those more powerful and influential than them, on the other are those who must take the decision of whom to punish, and how.

Dupindera Sandhu, an entrepreneur from Delhi, was in the final stages of inking a deal with Bold Kiln, a company that provides solutions to startups, when its founder and CEO, Abhishek Agarwal, was accused of sexual misconduct by multiple women on Twitter. “As soon as I read the accounts, I wrote to him, saying that we would not be going ahead with the deal,” Sandhu says. “Our business may not have been big enough to hurt him financially, but we were very clear that our company’s values did not allow us to work with someone who behaved so atrociously with women.”

While it was an easy decision for Sandhu — Agarwal is the face and the driving force behind Bold Kiln, and continuing to work with Bold Kiln, he says, would be akin to endorsing Agarwal’s behavior — he concedes that making the distinction between a company and its owner is not always quite as simple. “If he had been just one member of the team, our decision to work with the company would have depended on the company’s attitude towards the incident. Did they take immediate action? Do they take sexual harassment and discrimination issues seriously? If the company’s intent is to create a safe environment for its women employees, I don’t think others in it should have to suffer by association,” he says.

“Taking away the livelihoods and dreams of those who’ve done nothing wrong is not just damage, it is destruction. There has to be a better way to do this.”

Association can be a tricky thing to navigate. Where does one draw the line between complacency and complicity? One of the most enduring lines of criticism against Bollywood is that its silence is so long, and so complete, that it could almost be considered an endorsement of the behavior it shrouds. In Iqbal’s open letter, she speaks of many occasions on which Kashyap expressed disgust for Bahl and his behavior.

But the disgust is of little use when weighed against all the times they chose to share a stage with him, smile for photographs, and actively engaged in business deals that fattened the bank balance of a man they knew to be an aggressor, while his victim looked on. The hemming and hawing about complicated contracts aside, it cannot be denied that Kashyap chose to continue his association with Bahl, and benefited financially from it. For any meaningful conversation about the way forward, this choice needs to be examined, evaluated, and criticized.

“Look, I get that when shit hits the fan, it rains on everyone in the room. We had decided to drop Anurag’s name from Bebaak’s promotional material. But our film was still eventually dropped,” says Iqbal. “When Kevin Spacey was accused of sexual harassment, he was replaced in House of Cards and All The Money In The World; the projects weren’t scrapped for his crimes. Taking away the livelihoods and dreams of those who’ve done nothing wrong is not just damage, it is destruction. There has to be a better way to do this.”

While dropping Kashyap, or anyone else’s name doesn’t address the question of whether we, collectively, are okay with lining the pockets of those who, despite being in positions of power and influence, chose silence over accountability, one has to agree with Iqbal — there must be a better way, we just haven’t found it yet.

Sonali Kokra is a writer from Mumbai. She writes primarily on women's issues, relationships, culture, and lifestyle. In addition to writing, for the past 10 years, she has been attempting to make round chapattis at her mother's insistence. Currently, she is weirdly obsessed with smocks with pockets.

Related

Climate Change is Behind Increase in Miscarriage Along Bangladeshi Coast, Researchers Say