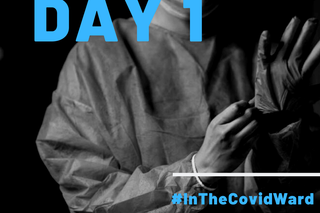

Doctor Diary, Day 1: “I Can’t Deal With the Fact That I Could Have Possibly Caused More Harm Than Good.”

“I can feel it getting worse,” she says.

A 28-year-old anesthetist working in the Covid19 I.C.U ward of a private Mumbai hospital, currently run by the BMC, shares the ups and downs of her days on the frontlines fighting the Covid19 pandemic. This is the first installment of a daily diary she shares with The Swaddle.

Early afternoon: Tracing labs I can feel it getting worse. I reached the hospital at 2 p.m. and it was chaotic already. We hadn’t gotten blood reports all morning. We don’t have a computerized system like the newer hospitals do. Everything is manually sent up and down between labs, and wards and the I.C.U. Even to send a sample of blood, we need people who have donned protective gear. We didn’t have enough people trained to do that — so we’ve just picked up people who are volunteering and we’ve trained them, but it takes time. Today, the labs were delayed.

Late afternoon: Doing rounds I usually sit outside the I.C.U, where there’s a little desk, before my afternoon rounds. I got a call that a patient was going bad. His breathing rate was increasing, his SATs (oxygen levels) were down from 95-100 to 70. He was agitated. In the morning rounds, he had said: “I don’t want to live, just let me go.” I tried to get him to calm down. We decided to ventilate him. I did the procedure, but there was so much technical error. The ventilator was stuck. I ended up intubating him, using manual ventilation with an Ambu. It’s an aerosol-generating procedure — you just hope you don’t get symptoms. Sometimes, the face shield is covered with so much sweat from the inside, it’s like you’re almost flying blind.

Today, the patient just kept crashing. In the end, he was conscious enough to understand what was happening. I reassured him he’d make it. In two hours, he was gone.

He had been talking to me right before he went down. He’d been my patient for a week. I remember his first day — he was one of the most cooperative guys we had. We really thought he would make it. I can’t deal with the fact that I could have possibly caused more harm than good. I don’t know if I have. That thought kills me. I tell myself I’ve done the best I could have, that there was no alternative. But would he have been happier if I had just let him struggle to breathe, without those procedures? It’s not for me to decide.

This wasn’t the first time something like this had happened. On my last shift, two patients died — one we had intubated and another we hadn’t. I don’t know what we’re doing wrong. Today, I’m thinking what if I hadn’t intubated? Would it have changed outcomes? We still don’t know what the disease really does. We don’t know for sure if our techniques are working or not working — are we doing something to cause patients’ death, or are we just doing procedures at the wrong moment, or is it just bound to happen?

It’s not that I haven’t seen death before. But I haven’t seen it in these many numbers before. Seemingly fine patients deteriorate so fast. Young patients don’t even come to the I.C.U; they have these sudden deaths. I don’t even know how many of those are happening outside the I.C.U.

The other patients, they’re not doing well either. One of the relatives of a patient was a doctor. It was hard — she understood everything I was saying. Usually, family members are naíve about the technicalities; it’s easier to talk to them. In this case, she asked for all the details of the medication and the procedures we did on her relative. You can’t falter.

But the patients are very kind. When you go and meet them, they offer you their food. Today, one guy offered me a sweet lime. It was such a kind gesture, I didn’t know what to say.

On the positive side, we did shift a patient out of the I.C.U. That was heartening. Not everyone does badly, but the ratio is starting to skew a lot these days. When the I.C.U started, we had patients on minimal oxygen support, minimal mortality. I hardly saw maybe one patient dying, even then they were people who had multiple other complications, who didn’t necessarily die from Covid19. But now, every other shift I see one patient dying, two to three patients getting onto ventilators. I’m giving poor prognosis to almost every patient. There are hardly any days without death.

I have to think of it professionally when I’m at work. When the patient is crashing, you have to focus on the numbers, the medical terms. You hold in all the emotion. I’m lucky I have PPE; the patients can’t catch it in my voice the few times I’ve not been able to control it. You can’t be weak when they’re relying on you to be strong. But it’s becoming more frequent, so maybe I’ll just get used to it. I don’t think that’s a good thing.

Evening: Filling death forms At 6:45, I left the I.C.U. and sanitized. I got a call that the patient I had intubated earlier had died. There’s one register that goes around the hospital for death, to jot down the names of patients who’ve died, the causes. I filled his death certificate.

I was told to inform the relatives. I can’t even describe to you how it feels. Being an anesthetist, I’m not even used to this. We are not one of those people who break news to families. We are in the operating theater, we are behind the scenes. Now suddenly I’m put in this position.

I contacted his wife. She was crying on the phone. I didn’t inform her immediately — first, we usually tell them he’s not doing well, building it up for 30-45 minutes. We usually give it at least a little time before breaking the news, because they’re always in denial if you suddenly spring up such news.

I watched a lot of videos on how to break the news so it’d be less hurtful, less blunt. You can’t dilly dally, you can’t give them false promises, but you have to be truthful, yet sensitive. You have to prime them. In the morning, you say it doesn’t look good, we have to get his blood pressure up, his SATS up. You tell them his X-ray is not looking good. They see that he is distressed while he’s talking on the phone, that he isn’t able to speak in sentences. They get the picture. You tell them his heart is weakening, you’re trying to push it to the limit, that it’s all on the drugs now. They keep saying please pray for us. At the same time, we have to reassure the patient that their family is doing okay.

Everything is over the phone. You can’t sit down with them, you can’t comfort them. This is all new to us. You just hope they understand.

Nightfall: Going home I told my reliever, who takes the hand off from me, about what exactly happened with each patient, which ventilators gave me trouble today. I head back to my hotel in Powai, where they’re putting us up. The first thing I do is shower, before touching anything else. We have a dabba service for dinner; my colleague usually picks mine up for me as I’m normally late. She also works in the I.C.U. with me, so at least I have someone to talk to. We usually discuss what we did and what we could have done, but after a while it gets depressing. Today, I broke down describing the patient crashing to my friend. Self-doubt creeps in these days. Quite often.

I talk to my parents and my fiancé every day to make sure they’re okay. I used to talk to my parents once a week — you get used to not being around them. This pandemic made me realize time is precious. It’s a conscious thing but I’ve been calling them every day. Its the simplest thing; it can be five minutes.

I’ve got my laptop here with me. Usually, I watch a little television before sleeping. I’ve been watching Fleabag. It’s quite quirky, I like it. I also watch World War II documentaries sometimes, although I don’t know why — they can get very depressing. Though tomorrow I have night duty, a good 12 hours.

I might just end up dozing. I don’t have any plans.

As told to Rajvi Desai.

Doctor Diary, Day 2: “Today, We Have a New Kind of PPE. I Was Drenched in Sweat After Two Hours.”

Related

Why We Feel Sleepy After Lunch