Muslims Comprise Only 1% of Characters on Popular TV Series, Finds New Research

“Not only is this radical erasure an insult, but it also has the potential to create real-world injury for audiences,” the researchers said.

Numbers often do tell a story, a rather murky one. Sample this: out of the 200 top-rated television series aired in the U.K., U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, only 1% of story arcs focused on Muslim characters and their stories. If these narratives existed at all, these shows were mostly linked to place their characters as “outsiders” and within the context of violent acts and behaviors.

These were the worrying findings of a report on Muslim representation on popular television shows. Titled “Erased or Extremists: The Stereotypical View of Muslims in Popular Episodic Series,” the study was published by researchers at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. The researchers looked at television shows that aired between 2018 and 2019, inspecting some 8,885 characters who had speaking roles across 200 shows. Think of programs like Eastenders, Next of Kin, Empire, Russian Doll, Grey’s Anatomy, The Simpsons, Jack Ryan, FBI, and more.

Out of these, there were only 98 Muslim characters across the massive breadth of characters crafted for television. There was one Muslim character for every 90 characters coming from other social backgrounds. And almost 87% of the series examined featured no Muslim characters. If one were to further dilute this number: there were 4,432 speaking characters across 100 shows in 2019. Only 11 of them were Muslim characters.

The report articulates the proliferation of cultural stereotypes through data, portraying a “disheartening reality of Muslims on screen.”

The question of representation must also spill over to consider what good portrayal should look like, and the damage harmful representation can do. This reality is also presented in violent and dehumanizing ways. For instance, more than two-thirds of the characters were portrayed as “foreigners,” people who aren’t native English speakers but “outsiders” to the cultural audience where these shows were being viewed. This is despite the fact that Muslims remain among the most racially and ethnically diverse religious group in the world — whose roots go beyond the Middle-east or North Africa.

In Jack Ryan, the Muslim characters shown in Nigeria were members of the Boko Haram militia. “If not directly involved in perpetrating violence linked to faith-based beliefs by the stories, Muslim characters were in military roles or were family and friends of extremists. In other words, when Muslim characters were located in Muslim-dominated countries, they were somehow connected to terrorist activity,” the study authors noted. Almost 37.2% of Muslim characters were shown as “criminals” in these shows, while 40% of characters were targets of violent attacks. Abundant research shows how religious, ethnic, and racial minorities are often otherized and alienated from the larger national identity.

Language becomes a site of violence too. The common words used to disparage characters on these shows went something like this: “terrorist,” “pedophile,” “monster,” “school shooter,” and “psychopath.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Tell Me More: Talking Muslim Identity In India With Ghazala Wahab

These depictions indicate how abruptly and violently the presence of Muslim lives can go “from mute to menacing,” as one op-ed noted. The crisis of representation is not limited to television alone. Last year, a study by the same researchers showed fewer than 2% of characters in movies released between 2017 and 2019 were Muslims.

The fact of gender here is also a pertinent inclusion. If the racist tropes show men as violent and aggressive, women are portrayed to be oppressed and caged to an anti-feminist system. The research showed that out of all the Muslim characters with speaking time, only 30% of them were women, and more than half of them were portrayed as women always wearing hijab. They were typically depicted in emotional and physical torment, and were almost always unemployed as compared to their male counterparts.

“We didn’t see them really leading their own storylines or showing them in empowering roles — which, again, creates this light that Muslim women cannot be leaders and they cannot be empowered,” said Al-Baab Khan, one of the authors of the study. And empowerment only ever comes by distancing themselves through stirring gestures from one’s religious values. Netflix’s Spanish teen drama Elite — although not considered within the ambit of this study — relies on this construction. One of the show’s leads, Nadia, walks into a club having removed her headscarf, drinks alcohol, and has sex with her white friend. “Instead of a nuanced approach to her identity, the once-oppressed teenager must make a statement,” argued writer and activist Mariam Khan.

Even shows that otherwise treat Muslim story arcs with sensitivity and care, such as Ramy, may not afford the same dignity to female characters. “Muslim women are indeed varied and complicated, but portraying them as largely absent of agency, or somehow wholly separate from the temptations or crises that Ramy himself navigates, excludes them from the modern millennial existence in a way that rings false,” noted culture writer Shamira Ibrahim in 2019.

One can make the argument that some representation is better than no representation, but they would be misguided. Such tepid attempts in the form of the “hijab-wearing cool Muslim,” as Sahar Ghumkor’s wrote inThe Political Psychology of the Veil: The Impossible Body, work towards a “normalization” of the western gaze. “It is through the very act of normalization, the one does not become human, but rather assimilated.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Indian Women Hold Only 10% of Directing, Writing Positions in Films and TV: Report

The implications spell out in bold, red letters — writings on the wall that can be read from a distance. On one level, “for Muslims, this sends a message that they don’t belong or don’t matter,” saidactor Riz Ahmed, whose production company Left Handed Films also funded the study. The stereotypes that find oxygen in pop culture create a blinkered understanding of what people look like and how they act, reducing them to caricatures representing a cultural and social identity, instead of real people with complex inner lives.

“[TV shows] play a big part in shaping how we understand the world, each other, and our place within it,” Ahmed noted. “This study reminds us that when it comes to Muslim portrayals, we’re still being fed a TV diet of stereotyping and erasure.” The cliches homogenize incredibly diverse narratives, cultural fissures, and individual identities — effectively making the line between social values and individual agency indistinguishable.

A cousin of the Bechdel test — which looks at women’s representation in pop culture — is the Riz Test.Its parameters are two-fold: are the characters in a TV show or film identifiably Muslim? And if so, are they portrayed as “terrorists,” “angry,” “anti-modern,” misogynists, or threats to western values? The bulk of cinema as it exists right now would fail this measure of authentic and meaningful representation. Stories of people who are Muslim spill beyond checking diversity boxes.

The conversation of representation on screen also lends itself to accountability in the real world. “Not only is this radical erasure an insult,” said Al-Baab Khan, “but it also has the potential to create real-world injury for audiences, particularly Muslims who may be the victims of prejudice, discrimination, and even violence.” These portrayals are implied forms of aggression, fostering a culture of fear of and around the community.

The scale and severity of Islamophobia have played out in stark terms globally, so much so that the anti-Muslim hatred reached “epidemic proportions” last year. An echo of this could be read within the backlash Ms. Marvel (2022), a Marvel TV show featuring a Muslim female character in the lead, received.

This epidemic of invisibility currently relies on prejudice and stereotypes that are monochromatic in nature. It screams of laziness, a rigid inertia to change and consider narratives beyond our pigeonholed worldviews. The counter naturally then lies in lending a shade of richness and color and complexity to people’s lives.

An instructive example comes in the form of Dr. Dahlia Qadri in Grey’s Anatomy or Omar Zidan in FBI. The said characters were presented as native English speakers, framed as co-workers, friends, citizens, or neighbors within the larger story arc. “This is an important way for media to showcase the reality that Muslims are community members rather than people who only live in other parts of the world,” the study authors noted.

Cinema, for all intents and purposes, continues to rely heavily on ethnic, racial, gendered, and religious stereotypes. But it can no longer disavow any responsibility for its real and reel reverberations. This is not just a storytelling industry producing mass entertainment, but a dynamic and reactive archive of people’s aspirations and anxieties. And while an industry is meant to typecast people, art must be held to greater responsibility.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

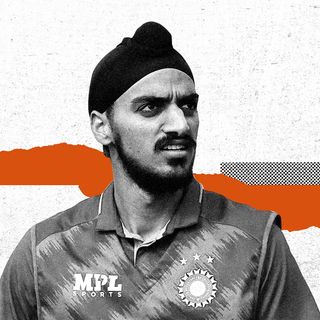

Hate Against Cricketer Arshdeep Singh Shows the Pitfalls of Sports Nationalism