My Teacher Saw My Talent in English That My Hindi‑Speaking Parents Couldn’t

Teachers can be powerful role models when we go beyond our parents’ comfort zone.

I don’t clearly remember the story, but I can remember how hearing it made me feel, like it was just yesterday. It was something to do with a donkey, a cat, a dog, and a rooster. And how they helped each other get rid of wicked thieves. I don’t remember the story, but it still puts a smile on my face and a warm, fuzzy feeling in my heart. It was my first real brush with the art of story-telling. I didn’t know then that the half hour spent in wide-eyed wonder was the start of a lifelong journey.

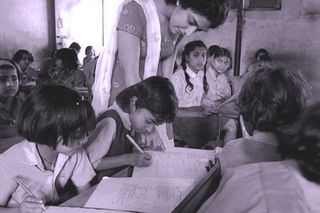

We were nine, maybe 10 years old when she came into our lives, her mop of impossibly curly hair forming a halo around her face as she threw her head back and laughed, which was often, and a lot. She had the kindest eyes I had ever seen on a person, even though I didn’t know what having kind eyes meant, or even had the words to describe them, then. I have her to thank, for the reasonably well-appointed vocabulary I’ve accumulated in the two decades since.

She was my English teacher in school, and the only person who saw talent in me, when no else in my universe could.

I come from a family of Hindi speakers. Mine was the first generation that received a private English education. My mother fought my grandparents for weeks, until exhausted, they reluctantly agreed to send my sister and me to the expensive English school a few miles away, instead of the government girls ‘pathshaala’ in the neighbourhood, but her own education was unequal to the task of tutoring us with much success, especially as our text books outgrew her limited stock of English words. The idea of employing tutors was broached, but my sister and I made it abundantly clear that we had no intention of attending extra study classes. We were both good students, with good grades, so our parents left us to our devices, on the condition that we’d be parcelled off to tuitions if our average went below 80%.

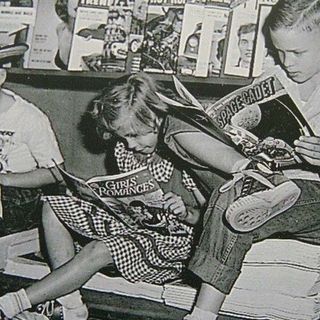

The arrangement worked beautifully, and we both enjoyed hours of daily free time, to fill with any activity we saw fit. My sister went on to become a sports champion, winning medals for her house and the school, while I could always be found with my nose buried in a book, skulking in some quiet corner at home or in school. Hers was a talent my parents could understand and quantify. They could see her jumping higher and longer than the others. They could feel the trophies she won. But how do you identify talent in a language you don’t speak? And so, they defined my kinship with the English language in the only way they knew — hobby. My sister had a talent, but I had a hobby. I believed it. Everyone around me believed it.

All of that changed when she came into my life.

I still remember the first time she called me to her desk after grading an essay-writing assignment. “Did you write this?” she asked me, her kind eyes looking at me with interest. It should have been a scary question for a 10-year-old to have to answer, but there was no anger or suspicion in her voice, just curiosity. I nodded, wondering why the new teacher was acting so strange. She smiled and told me I’d done a very good job, and that she wanted to read my essay out to the class. “May I?” She asked, and I nodded, my eyes wide.

I’ve had hundreds of bylines in my career as a writer, but nothing compares to the jubilation I felt as she read out my words. My words. I said the words over and over in my head for the rest of the week. The 10-year-old me didn’t know what to do with so much happiness.

“Your words deserve to be heard,” is what she told me.

Over the next few months, I devoted myself to making her proud. I spent hours in the library, reading above my level, trying to learn long, complicated words so I could impress her. I often used them incorrectly, forcing words into sentences they didn’t belong in, but she never laughed or embarrassed me. Every mistake was gently corrected, while every win was praised and celebrated.

To date, I think of those six years as the happiest time of my life. As we moved to higher classes, we had more senior English teachers assigned to us, but as far as I was concerned, she was the only one for me. Anything I ever wrote, went to her first for her approval and opinion. What she thought about my writing mattered more to me than what teachers far superior than her did. Before every vacation, I went to her for practice assignments and recommended reading lists. The quickest way to get me to write anything was to have her ask me to do it.

I hated giving speeches, but if she asked, I’d do it anyway. I remember the first time I was on stage, shivering with stage fright. Twice, I stood there staring at the sea of faces sitting below, and ran back into the curtains. She made me go out a third time anyway. “Your words deserve to be heard,” is what she told me before I finally went out and stumbled though the two pages I held in my shaking hands. I still hate making speeches, but I think of her and that day every time I’m invited to be on a panel or moderate a discussion.

My loyalty to her was absolute, and her investment in my success far exceeded the call of duty. She was my class teacher only for two years, but every open house of every year, she made it a point to speak to my parents. Thanks to her, they finally had a name and an understanding for my talent. “Our daughter writes” replaced “Our daughter’s hobby is reading” while talking to relatives and acquaintances.

Possessing a talent for something that your own parents aren’t equipped to understand, encourage, or support, even if for no fault of their own, can be a very lonely, confusing experience for a child. Every child needs that one adult who helps them discover, hone, and fall in love with their talent. For most people, that person is their parent. For me, it was my teacher.

In a world full of mid-life crises brought on by mind-numbing disinterest in the professions so many people my age have spent decades working in, I’ve never once wished for a different path. There are days and weeks and sometimes even months of panic, crises of confidence, hopelessness and the terrifying feeling of not being good enough, but never once have I fallen out of the love my teacher helped me discover two decades ago. Just for that, there is no thank you in the world that’s adequate or big enough.

Sonali Kokra is a writer from Mumbai. She writes primarily on women's issues, relationships, culture, and lifestyle. In addition to writing, for the past 10 years, she has been attempting to make round chapattis at her mother's insistence. Currently, she is weirdly obsessed with smocks with pockets.

Related

A Historically Stuffy Sport Becomes a Cultural Flashpoint