Researchers have developed a new blood test that can help predict the development of active tuberculosis up to two years before its onset, in people who live with someone ill with active TB.

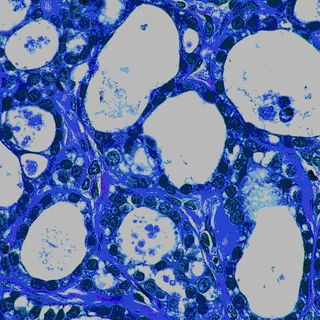

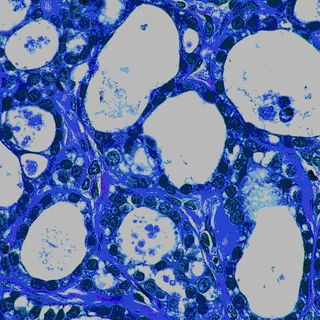

Tuberculosis, which is caused by infection with Myobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), is the world’s leading cause of death brought on by a single pathogen. India has the highest TB burden of any other country; its 2.8 million cases represent a quarter of the global disease burden. Earlier this year, the government launched a campaign to eradicate the disease by 2025.

People living with someone who has active TB are at the highest risk of developing the disease as well. However, only 5 to 20% of people infected with M.tb actually go on to develop tuberculosis. Presently, there is no available blood test that predicts whether a latent M.tb infection will become active TB without putting low-risk people through a tedious, unnecessary process of treatment.

But in a new study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care, researchers from an international research group report they have developed a blood test that measures the expression levels of four genes that helps more accurate predict the development of TB in high-risk sub-Saharan patients. A genetic signature known as RISK4, which is a combination of four genes associated with inflammatory responses, presented in all study participants, who came from South Africa, Gambia and Ethiopia. The team focused on individuals who lived with someone with active TB, enrolling 4,466 participants who were HIV-negative and healthy, from households of 1,098 active TB patients.

After initially collecting blood samples, researchers compared the samples of the 79 individuals who had progressed to active TB within 3 to 24 months post exposure, with the other 328 participants who remained healthy during the 2 years of follow up. Various biosignatures — combinations of gene or protein levels that together result in a test readout that relates to current or future risk for developing the condition — were also measured.

The result is a not fool-proof, says Gerhard Walzl, PhD, lead study author and leader of the Stellenbosch University Immunology Research Group in Tygerberg, South Africa. But it gives positive results for a smaller percentage of people living in high-risk household than current tests, which could translate to fewer people receiving unnecessary preventative treatment, which often stretches over several weeks and comes with many side effects.

Still, there’s a long way to go before the RISK4 marker is proven to predict TB for other populations and the genetic test can be developed into a standard offering.

“This study is the first step, and now the impact of this test on prevention of TB will have to be tested in multicenter clinical trials,” Walzl says. “In addition, the validity of the prediction in high-risk individuals in Asia, South America and other high-priority areas needs to be assessed.”