Women whose paternal grandfathers and great-grandfathers started smoking before the age of 13 share one trait: they reportedly have higher body fat mass, according to new research. While research so far has focused attention on early smoking to health issues like asthma and lung impact, the genetic link impacting body fat is underresearched.

Published in the journal ScientificReports last week, the study is among the first pieces of evidence to argue people’s exposure to certain substances may affect generations that follow. The present research gleaned information from three generations within a family, drawing parallels between the health and social aspects.

What’s quite pioneering is the longevity and scope of the study. The research, under the Children of the 90s project and led by the University of Bristol, has been studying a cohort of more than 14,000 individuals born in 1991 and 1992 in the U.K., along with their parents, for 30 years. The present study chose to pick the dataset pertaining to male smoking, with the researchers noting smoking among grandmothers and great-grandmothers would have been a relativelyrarer habit.

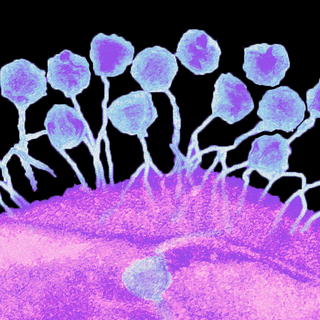

This is not the first time the phenomenon was discovered. Earlier research from 2014 showed a father’s smoking habits, if they started before reaching puberty (before 11 years of age), influenced the son’s body fat more than expected. Additionally, other experiments done on animals have found that when the male is exposed to chemicals before breeding, it can impact the anatomy of the offspring. However, scientific evidence has remained tepid in substantiating whether this trend is present in humans and what factors could be at play here.

“If these associations are confirmed in other datasets, this will be one of the first human studies with data suitable to start to look at these associations and to begin to unpick the origin of potentially important cross-generation relationships,” said Jean Golding, the founder of the Children of the 90s study and the report’s lead author, in a news release.

Related on The Swaddle:

How Secondhand Smoke Is Harmful In the Long and Short Term

The study highlighted “strong relationships which were sex-specific, both regarding the sex of the exposed grandparent and the sex of the affected grandchild.” The body fat and smoking link were observed between paternal grandfathers and women only. Moreover, another finding from last year linked exposure to smoking in the paternal side of the family — before puberty — was associated with increased risk of asthma, reduced lung capacity, and increased fat mass in the offspring.

Arguably, the intergenerational link between ancestors and children’s anatomy is observed in other cases. 20 years ago, research found women who eat oily fish during pregnancy were more likely to have children with sharper eyesight. This was among the first correlations between a woman’s diet and a child’s visual development. Some links were also made in children as young as eight-years-old, and finding markers of Type 2 diabetes in their blood from such a young age — about 50 years before it’s commonly diagnosed. The researchers noted, “this is about liability to disease and how genetics can tell us something about how the disease develops.”

The interaction between smoking and genetics binds both — how we view both smoking and obesity as public health challenges. A similar study in 2018 suggested smoking has a greater effect on the body mass index (BMI) and obesity-related traits than expected. In other words, a person’s odds of being a smoker was higher if they had excess body fat — even though smoking has long been associated with being relatively thin. Published in PLOS Genetics, the research highlighted the “potential of using biomarkers as a measure of an individual’s past environment and lifestyle.” Moreover, the environment we experience “may have long-term effects by altering the way our genetic makeup influences our health and related traits.”

There also seems to be a circularity between smoking and obesity. United Nations scientists in 2018 cited research to state obese people were more likely to smoke; identifying a “common biological basis for addictive behaviors, such as nicotine addiction and higher energy intake.”

If there is a genetic relation here, it may shed new light on how we view obesity. “One of the reasons why children become overweight maybe not so much to do with their current diet and exercise, rather than the lifestyle of their ancestors,” added Golding.

For now, there remains “much more to explore.”