Why You Can’t Shut Your Mind Off Even When You Know You Need to Sleep

Dwelling on problems is an attempt at closure. Too bad it doesn’t work.

At least three out of seven mornings, when my husband asks me how I’ve slept, I tell him not well — “I just couldn’t shut off my brain.”

My thoughts are about what I could have done differently — what I could’ve done better. Often, they’re about wording, both spoken and written — an occupational hazard. I edit myself over and over again, changing words and actions with every toss and turn, until it all turns into a morass of mistake and error, and I pass out from the sheer weight of my failure. Or, you know, from exhaustion.

I don’t feel like a failure, though. I wake up the next morning sleepy but ready to get going, often having forgiven myself — and chalking up my nighttime soul-searching to lessons learned and problem solving for next time.

The thing is, this type of obsessive replay is very different from active problem solving. It’s called ruminative thinking, and it can actually make it much more difficult to come up with solutions to the problems you face.

Obsessive rumination is different from anxiety in that obsessive rumination is worry over negative things past, rather than worry over potential negatives in the future. That said, they’re similar states, and over-reflecting can contribute to anxiety and even depression. And like anxiety, obsessive rumination is much more common among women than men. (Some research suggests hormone fluctuations might heighten the tendency toward rumination and anxiety, while other studies point to the influence of social and life experiences that are more common among women than men — for instance, physical and mental abuse — that shape thinking patterns.)

Related on The Swaddle:

There Are Three Types of Perfectionist. Which One Are You?

Reflection is always beneficial, but the thing about rumination is that, by its nature, it is reflection that doesn’t lead anywhere — it’s just a vicious cycle.

People who ruminate “will often spend hours analyzing the situation, even after they’ve developed a plan for dealing with the situation,” writes psychologist Edward A. Selby, PhD, who doesn’t know me, but also knows me. “Sometimes people will ruminate about the problem so much so that they never even develop a solution to the problem. This is where rumination becomes really problematic. If the situation has you in a bad mood, rumination will keep that bad mood alive, and you will feel upset for as long as you ruminate.”

It has other effects, too. Holding onto the negative thoughts can lead to self-sabotage of any solutions you do come up with. It can also inhibit working memory (so can the lack of sleep from nighttime ruminating like mine).

So, why do we do it? For me, it’s a coping mechanism, though not necessarily a healthy one.

“The dwelling seems to stop the immediate pain or distress, the way rubbing a sore muscle can relieve the soreness temporarily, until you stop rubbing,” writes Melissa Kirk, in an essay describing her struggles with obsessive rumination. “Also, I feel like, when I’m ruminating, that I’m acting on the problem by trying to solve it.” The problem is, of course, that most of the time we’re ruminating on unsolvable problems: things that have already happened, that we can’t go back and change.

What we can affect, however, is the present and future. And changing any current ruminative tendencies starts with becoming more aware about the patterns of your obsessive thinking. When do you tend to do your rumination? (At night.) What do you typically ruminate on? (Work mistakes.) When you do ruminate, do you typically blame yourself, or others? (Myself.)

At that point, it becomes about taking the negative sting out of your thoughts, as well as disrupting their repetition.

Author and psychologist Alice Boyes recommends a few tricks. One is to analyze what’s running through your head and distinguish between beliefs and feelings. “So instead of saying ‘I’m inadequate,’ you might say, ‘I’m feeling like I’m inadequate,'” she writes.

Related on The Swaddle:

Your Anxiety Might Actually Serve a Purpose

She also advises checking for any entitlement or self-centeredness in your interpretations of whatever it is you’re dwelling on. If you spot it, think of the realization as bringing objectivity, or even levity, to your ruminations, rather than as an “indictment on your character” for being a self-absorbed jerk, suggests Boyes, who also doesn’t know me, but knows me.

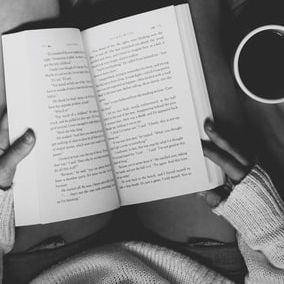

Similarly, she advises running your thoughts through a bias-check for assumptions you’ve made that might be coloring your thoughts more negatively than they need to be. “I’ll often read a work-related email and zone in on one or two sentences that irritate or upset me and then misinterpret the overall tone of the message as demanding or dismissive,” she writes.

And then, of course, it becomes about shifting yourself into problem-solving mode. “Ask yourself, ‘What’s the best choice right now, given the reality of the situation? Start by taking one step, even if it’s not the most perfect or comprehensive thing you could do,” Boyes advises. “If you’re ruminating about a mistake you’ve made, adopt a strategy that will lessen the likelihood of it happening again.”

All helpful advice, but the problem with my particular flavor of rumination, is that I often reach a solution quickly, but continue to dwell on the initial mistake. I’m aware of, and tortured by, my inability to move on, even with a solution in hand and the rational understanding that no matter how much I dwell on it, what is done, is done.

For this, Boyes, and most experts, offer one more tip: Physical activity. Exercise has been proven to improve mood. It can also help center your thinking, as can mindfulness activities like yoga. Anecdotally, this is the only thing that has worked for me, but for reasons most experts probably wouldn’t expect: Exercise simply makes me too exhausted to ruminate.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Why Cancelling Plans Gives Us Such a Rush