The Revolutionary Origins of the Term ‘Male Chauvinist Pig’

The term is the brainchild of the feminist, communist, and civil rights movements of the 60s.

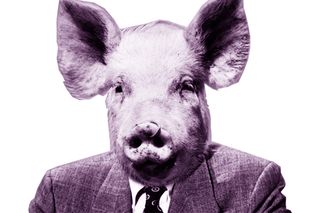

Everything you know about the phrase ‘male chauvinist pig’ is probably wrong, thanks to popular culture diluting it into a rather hip ‘M.C.P.’ The phrase doesn’t only apply to men; chauvinism has nothing to do with gender, etymologically; and, ‘pig’ here is not used in the sense that men are literal swine, but is actually an Orwellian reference, which has further roots in communism and the civil rights movement in the U.S.

From the beginning, and especially from the 1960s onwards, naming women’s unique experiences, and creating a common language among them was crucial to the women’s movement. Feminists grappled with the elemental question of what to call the men — in relation to women — who treated women as inferior and/or sexual objects.

The term ‘male chauvinist’ and its extension ‘male chauvinist pig’ emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s among feminists for men in positions of power who believed in the superiority of men, and lived out that belief in words and actions. It originated as a mashup of two previous movement-related words: ‘chauvinist,’ named after Nicolas Chauvin, an extreme patriot in Napolean’s army; and, ‘pig,’ which emerged as a term during the 1960s and 1970s by student activists during the American Civil Rights Movement to denigrate the police, and by extension, those with the power to oppress.

Breaking it down

‘Chauvinism’ from the French chauvinisme, emerged from the character Nicholas Chauvin in playwright Théodore Cogniards’ popular 1831 vaudeville show, La Cocarde Tricolore. Chauvin was a hyper-loyal soldier in Napolean’s army who idealized him and the Empire, even after being wounded 17 times and significantly maimed.

The name was common in Napoleon’s army, so some believe the character is based on a real person. But, etymologists are yet to identify him with certainty, since no biographical records can be found about him — save one memoir of Waterloo, which mentions “one of our principal piqueurs (French for an attendant who drives the hounds during a hunting session), named Chauvin, who had returned with Napoleon from Elba,” according to the Online Etymological Dictionary. After Napolean’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, such blind and exaggerated patriotism began to be mocked — thereafter, ‘chauvinism’ came to mean an extreme or bigoted form of nationalism to the extent it became a vice.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Difference Between Sexism and Misogyny, and Why It Matters

“At some point in the late nineteenth century, the American Communist Party (CP) adopted the term ‘chauvinist’ to describe the nationalism it considered inimical to the interests of the workers. Later, the experience of trying to recruit extensively among [African] Americans in the United States led the CP to adopt two new phrasal terms, ‘race chauvinism’ and ‘white chauvinism,’ to derogate the conviction of whites that they were better than black people,” Harvard University’s Jane Mansbridge and Katherine Flaster write in “‘Male Chauvinist,’ ‘Feminist,’ ‘Sexist,’ and ‘Sexual Harassment’: Different Trajectories in Feminist Linguistic Innovation.” Inspired by the CP’s struggle against racism, women in the CP coined the term ‘male chauvinism’ to diminish the conviction of men that they were the superior sex. By that logic, even women could be male chauvinists; the term did not describe men who were chauvinists, but people who were chauvinistic about males. By the late 1920s and 1930s, ‘chauvinism’ had been reclaimed away from the language of nationalism to that of racism and sexism.

From the mid-1950s onwards, the American Civil Rights Movement began picking up steam, with black Americans rallying for equal constitutional rights as those of whites. In this era, the CP also extended the word ‘pig’ as a reference to police and other figures of authority, alluding to the oppressive Pig Laws that white southerners created after the American Civil War and the abolishment of slavery in the 1860s, which were aimed at compensating for the loss of a steady stream of free (African American slave) labor. One of the laws made the punishment of stealing a farm animal steeper than other kinds of theft because it was a crime disproportionately committed by African Americans in the decades after the Civil War — with no consideration that this was more likely a desperate attempt to find food.

The popularity of the slang ‘pig’ for the oppressive powers-that-be only grew with George Orwell’s classic and revolutionary Animal Farm in 1945 — an allegorical novella in which animals in a farm rebel in the hopes of an equal society, only to have the rebellion betrayed by the Pigs, who after the revolution establish their leadership under a dictatorial Pig neatly called — Napolean. Ironically, Animal Farm — and the Pigs in it — was really a critique of communism; the Pig Napolean was actually based on Joseph Stalin.

A few decades later — in the 1960s and 1970s — the second wave of the feminist movement was also gaining ground. “Particularly in the younger branch of the movement, the children of former CP members who had picked up the term ‘male chauvinist’ from their parents began using it in active feminist circles. The term caught on,” co-write Mansbridge and Flaster. Their linguistic analysis of the term found that “in 1968, one article appeared in the New York Times using the word. The next year, eight articles appeared. Then 48 articles the next year, and 76 the next. In 1972 the number soared to 130,” with the usage of the word ‘male chauvinist pig’ also peaking that year, as can be seen by the following Google NGram, a statistical analysis of all books, articles and print text between 1800 and 2000 for any given phrase(s).

Mansbridge and Flaster argue that the addition of the word ‘pig’ to ‘male chauvinist’ gave the phrase greater popular appeal, “first, by helping someone who didn’t know what ‘chauvinist’ meant, guess the meaning of the phrase, and second by allowing the phrase to pass as a joke. ‘Male chauvinist pig’ had just the right tone of improbability to lighten the criticism as a teasing term, expressed in fun, in a way that the more serious ‘male chauvinist’ could not,” they write.

“There are few references to MCP or male chauvinist pig in feminist writings. A 1968 Ramparts included the sentence, ‘Paternalism, male ego and all the rest of the chauvinist bag are out of place today.’ The New Yorker used it the same year as ‘male-chauvinist racist pig.’ The abbreviation MCP appears as early as 1970 in Playboy magazine,” Jone Johnson Lewis writes in ThoughtCo.

Related on The Swaddle:

From ‘Cunt’ to ‘Careerwoman’: the Many Ways in Which Language Propagates Sexism

Ironically, the phrase was most commonly used — in print and in interview transcripts — by men, Lewis writes, “sometimes to confess a past as an MCP, and some to proudly carry the title.” A 1971 Hush Puppies ad for two-toned sneakers which basically look like a clown’s bowling shoes proudly markets to its key demographic for the shoe: male chauvinist pigs. The copy read: “ATTENTION MALE CHAUVINIST PIGS. Relax. When the ‘Libs’ call us names like that it really means they think we’re rugged, masculine, virile. Like these new Hush Puppies…”

From the 1970s onwards, the newness of the second wave of feminism had started fading, and the movement slowly started turning towards more institutional language and venues. ‘Male chauvinist pig’ lacked the formality and structure the movement was looking for; it failed to serve as a central point connecting the various issues women were facing, such as equal access to jobs and sports, equal pay, right to safe abortion, and breaking the corporate glass ceiling. Many liberal feminists resisted using the term since it fit into the media image of feminists as man-haters. Others resisted the term since it objectified men, reducing them to an animal when feminists were criticizing similar objectification of women.

It was hard to philosophize ‘MCP,’ as opposed to the more formal words ‘sexism’ and ‘sexual harassment.’ The latter words originated in the same era but succeeded in cementing themselves as the words essential to the feminist movement’s lexicon, as it tried to pick apart society’s patriarchal superstructure.

By the second half of the 1970s, the usage of ‘male chauvinist pig’ started dwindling, but where it disappeared from the feminist discourse, it appeared in everyday conversations. Mansbridge and Flaster write of a telephone survey they came across in their research: “In 1992 and 1993, the Northwestern Survey Laboratory’s Chicago Area Survey asked a representative sample of Chicago area residents, “Have you ever referred to someone as a ‘male chauvinist,’ either while speaking directly to that person or in describing that person to someone else?” Both in 1992 and 1993, 63% of the women in the metropolitan area sample said that they had used the phrase to describe someone they knew.”

Most recently, the word has been used frequently before, during and after the U.S. presidential elections for Donald Trump — a man adept at reigniting the collective feminist, communist, and civil rights fervor of the 60s — by the sheer ferocity of his very public sexism, capitalistic greed, and racism. The word might not have made it to the ranks of ‘sexism’ and ‘feminism’ within the women’s rights movement’s vocabulary, but it looks like it’ll stick around in locker rooms, for as long as Pigs rule.

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Related

Lack of Infrastructure, Awareness Means Female Athletes Seek Help for Concussions Later Than Male Athletes