The Human Mind Wasn’t Meant to Stay Awake Past Midnight

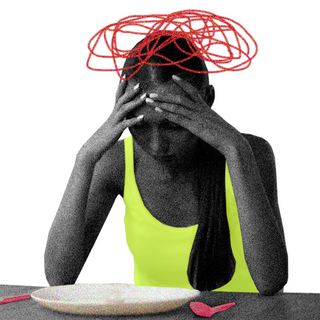

Midnight makes the brain inclined towards addictive behavior, suicidal ideation, and other high risk situations.

A new hypothesis, published this year in Frontiers in Network Physiology, states that the human mind is not meant to be awake after midnight. The researchers behind the study claim that after midnight, an awake mind is more attentive to negative emotions than positive ones. They highlight that the mind may even find ideas of self-harm more appealing if it stays up for long beyond bedtime. The research suggests that the human circadian rhythm — the internal natural process of the body that synchronizes the sleep-wake cycle every 24 hours — has a significant role to play in these fluctuations.

Previous studies have looked into the fallout of fragmented or insufficient sleep, such as increased stress, cardiovascular diseases, and dopamine fluctuations that could even lead to addiction. Uninterrupted sleep during the night, moreover, results in better cognition and overall healthier functioning during the next. The researchers took this into account and sought to examine whether nocturnal wakefulness, or choosing to stay up during the circadian or biological night, leads to maladaptive behaviors — behaviors against a person’s own self-interest — such as violent crime, substance use, and even suicidal ideation. In their research, the scientists state that they evaluated “how mood, reward processing, and executive function differ during nocturnal wakefulness.”

The researchers examined empirical data from existing studies on sleep and its effects on cognition and functioning. They suggest that the human body and mind follow a circadian clock — it is meant to act and feel in certain ways at certain hours. Hence, while in the daytime molecular and brain activities function in full swing, at night the body seeks rest.

There might also be an evolutionary reason to explain how nocturnal wakefulness influences maladaptive behavior. When humans were evolving in the wild, there was a great risk of being hunted during the night; as a result, the brain heightened its attention to negative stimuli during this time. Today, in the absence of such external risks, this hyper-focus on the negative has resulted in an altered reward/motivation system and has consequently made humans more prone to risky behavior. Hence during nighttime sleeplessness, humans are at a heightened consciousness and they may feel encouraged to engage in more harmful behavior.

Related on The Swaddle:

Why Young Indians Continue to Sacrifice Sleep

Citing a personal experience to the Mass General Research Institute — an affiliate of Harvard Medical School — the lead author of the study Elizabeth Klerman recounted her ordeal of finding sleep in Japan after severe jet lag. “While part of my brain knew that eventually I would fall asleep, while I was lying there and watching the clock go tick tick tick—I was beside myself,” she recalled, adding “Then I thought, ‘What if I was a drug addict? I would be out trying to get drugs right now.’ Later I realized that this may be relevant also if it’s suicide tendencies, or substance abuse or other impulse disorders, gambling, (or) other addictive behaviors. How can I prove that?” This thought led to her working with her colleagues in formulating what they named the ‘Mind After Midnight’ hypothesis.

A piece of key evidence that helped shape the hypothesis was a 2016 study published by the National Library of Medicine, USA that found that suicides were statistically most likely to occur during nighttime. That study stated that there was a three-fold increase in suicides from midnight to 6.00 AM than at any other point of the day. Another research, at a supervised drug consumption center in Brazil, discovered an almost five-fold higher risk of an opioid overdose at night.

Existing evidence on shift workers — medical workers, pilots, firefighters, etc — shows that their unusual sleep patterns lead to health problems such as insomnia, caffeine addiction, and a general feeling of being unrested. Klerman and her colleagues’ hypothesis, if properly examined, could point at directions that could be taken to investigate how to protect these workers, and several others, from the harmful effects of nocturnal wakefulness.

Amlan Sarkar is a staff writer at TheSwaddle. He writes about the intersection between pop culture and politics. You can reach him on Instagram @amlansarkr.

Related

How Extreme Self‑Focus Can Prevent ‘Shy’ People From Bonding With Others