What Does It Mean When New Research Debunks Parenting Buzzwords?

Are growth mindset and delayed gratification not important anymore?

Last week, we reported that a re-creation of the famous 1960 Stanford “Marshmallow Test” had upended the original study’s findings that children’s ability to delay gratification was predictive of their school and life success. The importance of delayed gratification had been a cornerstone of developmental psychology, and informed much of early childhood education curricula and parenting advice in the latter half of the 20th century.

Now, new research is calling into question another, more recent parenting buzzword: growth mindset, the belief that intelligence, skill and performance can adapt, change and improve through effort. (Its counterpart, fixed mindset, is the belief that intellect is static and inherent, and that failure is due to lack of ability.) The importance of growth mindset burst onto the social science scene in the early 2000s, and in just the past decade and a half, has become one of the most dominant guiding philosophies of education reform and parenting advice.

But should it have? A team of researchers from Michigan State University and Case Western Reserve University, in an effort that combined and analyzed two meta-analyses of the results of hundreds of previous mindset studies, found many did not follow best practices for experimental research; for example, more than one-third did not check whether the mindset intervention in question actually had any effect on students’ mindsets.

It’s not the first time growth mindset research has been under fire. Studies by Carol Dweck, the originator of mindset theory, were criticized just last year for not following best practices — though there are enough, more rigorous studies by other academics that support her findings. The Stanford Marshmallow Experiment in hindsight has also been known to be flawed in its execution, focusing on a small cohort of very similar children from similar, highly educated and fairly wealthy family backgrounds.

But where does that leave parents and teachers who have poured their efforts into instilling these traits in kids — and the kids themselves?

Perhaps not so high and dry. First, it’s not like the ability to delay gratification is an unimportant skill, or the belief in one’s ability to learn and improve a bad attitude for children to have. Second, these theories’ popularity may well be exactly why the results of this later research differ from the original findings. As awareness of these theories has spread, more children gained these skills and mindsets, producing an equalizing effect that may have allowed other traits and attitudes to gain more influence on variations in future success and achievement, suggests psychiatrist Dr. Grant Hilary Brenner at Psychology Today.

“I can’t help but wonder if kids have learned to be able to wait longer because of the Marshmallow Experiment, the broad exposure it has had, and potential effects on education and child-rearing,” Brenner writes.

Finally, the word ‘debunked’ might be a bit of a misnomer. The latest study to questioning the importance of growth mindset to education and parenting did find a minor correlation between growth mindset and academic achievement, one that was stronger in children than adults. Second, their criticism is rooted in a lack of data, not in an analysis of data that proves growth mindset ineffective: More than one-third of the mindset studies they analyzed collected zero data on children’s mindset after the program ended to see if mindset actually changed. The researchers themselves are calling for more research and more data.

In the end, what these latest studies are evidence of, is not that parents and educators have been misled by early childhood development theories around delayed gratification and growth mindset. Rather, that there’s no magic bullet for raising successful kids. Both of these skills are likely important — just like all the rest of life skills.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

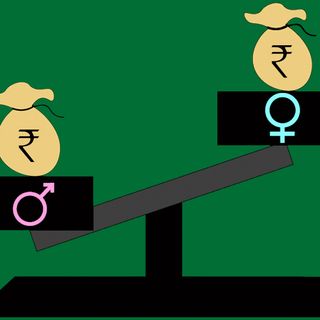

India’s Wage Gap Exists Even at the Highest Education Levels