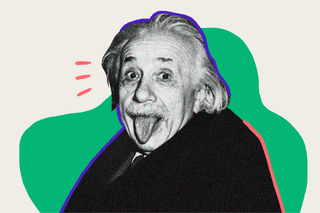

People Find Nonsense Credible if They Think a Scientist Said It, Shows Study

According to the “Einstein Effect,” people are likely to find “pseudo-profound bullshit” more credible if it comes from scientists rather than spiritual gurus.

The profound aphorisms that you don’t quite understand but which you may nod along to or even forward to others may not actually mean anything, new research suggests. It could be an internal bias that suggests a statement is credible — even if it doesn’t appear to mean anything — if it is implied to be coming from a scientist. There’s a name for this phenomenon now: the “Einstein Effect.”

A team of international researchers used a nifty little algorithm — with a rather on-the-nose name of “New Age Bullshit Generator” — to see how people respond to meaningless statements that sound profound. The team sought to determine whether people found such statements more credible if they believed they came from scientists, or from spiritual gurus.

The Bullshit Generator is a real algorithm that can generate a “full page of New Age poppycock,” at the click of a button. The study included more than 10,000 participants from 24 countries, who were asked to rate the credibility of various statements generated by the algorithm, and also self-report their religiosity.

“We found a robust global source credibility effect for scientific authorities, which we dub ‘the Einstein effect’: across all 24 countries and all levels of religiosity, scientists held greater authority than spiritual gurus,” the paper, published in Nature Human Behaviour, noted.

In other words, irrespective of people’s religious leanings or beliefs, science was found to be a powerful thing across cultures. It signals “reliability of information,” the authors write. They explain that this is important from an evolutionary perspective: deferring to authorities who are considered credible was an important strategy for adaptation and knowledge transmission. “Indeed, if the source is considered a trusted expert, people are willing to believe claims from that source without fully understanding them,” they write.

But the incomprehensibility could add to the credibility in some cases, a phenomenon that the researchers have dubbed the “Guru” effect. All in all, however, even those with higher intensities of religious beliefs indicated greater credibility scores for the scientists’ nonsense. In other words, “gobbledegook from a scientist was considered more credible than the same gobbledegook from a spiritual guru.”

Related on The Swaddle:

A Research Competition Wants to Debunk ‘Cow Science.’ Do Facts Stand a Chance Against Beliefs?

What this tells us is that at some point, scientists bypassed religious and spiritual leaders as the most credible sources of information across cultures. 76% of all participants rated the scientist’s “gobbledegook” — referred to in the literature as “pseudo-profound bullshit,” the authors helpfully add — at or above the midpoint in the credibility scale. Only 55% did so for the spiritual guru.

While the research does note that the smallest difference in credibility scores between spiritual leaders and scientists were found in Japan, China, and India, this could be because the spiritual gurus represented in the study fit Eastern religious systems more.

The positive takeaway is the level of trust in science over spirituality, but there is a downside: the study shows how our gullibility to nonsense can be manipulated. “Only a small minority of participants, regardless of their national or religious background, displayed candid scepticism towards the nonsense statements,” the authors observed.

The study’s limitations include the fact that it included “sources” largely considered to be benevolent; and there were no stakes or incentives for accuracy, prompting participants to perhaps save their cognitive energy and trust the purported benevolent source. The researchers also included statements that weren’t about politicized topics like climate change or vaccines. “By using ambiguous claims without any specific ideological content, we tried to isolate the worldview effect regarding the source from any worldview effect related to the content of the claims,” the paper noted

The implications are still concerning. The Einstein effect could potentially be enlisted to sell us more products — claiming that they are “scientifically” proven to work. And, perhaps, companies may have begun using it already — even before scientists developed its nomenclature. The tobacco industry had used this to convince people not to worry about the effects of smoking. Most notably, the wellness industry too — think Goop — is notorious for roping in a scientist or two to validate their claims and new-age health jargon, with deliberately concealed information and carefully crafted statements to avoid liability.

“This work addresses the fundamental question of how people trust what others say about the world,” say the authors of the study. So, the next time a WhatsApp forward peddles information or “pseudo-profound bullshit” citing NASA, WHO, or other such lofty scientific authorities, a little fact-checking would be in order.

Rohitha Naraharisetty is a Senior Associate Editor at The Swaddle. She writes about the intersection of gender, caste, social movements, and pop culture. She can be found on Instagram at @rohitha_97 or on Twitter at @romimacaronii.

Related

Scientists Found the First Dinosaur With a Respiratory Disease