Period Tracker Flo Has Been Sharing Users’ Health Data with Facebook, Reports WSJ

Just when you thought the social media platform couldn’t get any more creepy.

The popular period tracking app Flo has been sharing user data with Facebook, informing the social media giant of every log in, and every time a user told the app she intended to get pregnant, reports the Wall Street Journal. Regardless of whether the Flo user had a Facebook account, Facebook would receive data on “where the user was in her menstrual cycle — ranging from ‘ordinary’ or ‘period’ to ‘ovulation’ and ‘pregnant.'”

Moreover, the Flo data “was sent with a unique advertising identifier that can be matched to a device or profile,” WSJ reports — meaning Facebook could match the dates of your period and ovulation with your actual Facebook account, allowing Facebook to target ads specific to individuals’ menstrual cycles.

Flo, with 16.1 million downloads in the last 12 months, is one of 11 popular apps uncovered by the Wall Street Journal investigation that share data with Facebook without users’ permission. The period-tracking app, whose privacy policy states it will not share “information regarding your marked cycles, pregnancy, symptoms, notes and other information that is entered by you and that you do not elect to share” to third parties, has since said it will stop sharing sensitive data with Facebook’s analytics software.

Related on The Swaddle:

Period Tracking Apps Are a Contraceptive Gift to a Tech‑Savvy Woman… Or Are They?

Facebook also responded by saying the data sharing violated its terms of business with app developers, which advises apps who use Facebook Analytics software not to share users’ health, financial or other sensitive information. But the software itself is set up to do precisely that; the tool used by Flo and other apps allows Facebook to “see statistics about … users’ activities — and to target those users with Facebook ads.” And in fact, the terms of business also allow for Facebook to “use that data uncovered by the Journal for other purposes,” per the WSJ report, though a Facebook rep told WSJ the platform doesn’t do that.

It’s a claim that rings hollow from a company known for its pattern of private data invasion and profiteering. In the past two years, a slew of reports has uncovered that the social media platform makes its money by selling data on its users’ behaviors, interests and activities to the highest paying advertiser, enabling political manipulation via user data (with genocidal results), and intentionally enticing children into high spending on online gaming.

The effect of Facebook knowing your menstrual data may seem minimal in comparison — after all, what is an extra tampon advert in your newsfeed the day before your period begins? — but aside from the possibility of emotional distress from ads targeted around fertility, there’s a very real risk that women’s menstrual data may be used against them. Those “other purposes” could well involve selling your menstrual data to, say, a matrimonial website, which could offer grooms’ families information on your fertility based on information you assumed was private to Flo. Guess we’ll just have to take Facebook’s oh-so-trustworthy word this won’t happen. (While Flo has issued iOS and Android updates that prohibit the sharing of user data with Facebook in the future, it’s unclear what will happen with the menstrual data Facebook has already amassed.)

Facebook could also sell your menstrual data to insurers — that is, if the period tracking app isn’t already doing so. Femtech isn’t known for its safe-guarding of users’ data. In fact, the CEO and co-founder of Glow, another popular period-tracking app, has suggested the app might allow users’ data to inform health insurance offerings, by enabling “more accurate risk assessments … which will ultimately result in better health insurance” — but better for whom? the insurer, or the users?

Chances are, not the users. Risk assessments are based on what is considered normal and healthy, and criticism of period-tracking apps has also focused on how they marginalize anyone who doesn’t fall into a very narrow definition of normal menstruation. Maggie Delano writes on Medium, as she chronicled her attempts to use Glow and Clue, another popular period-tracking app, only to find they didn’t allow her to record her short, irregular cycles: “I literally cannot even enter my actual cycle length. My cycle length is shorter than 22 days right now. The Glow app seems considerate enough of people who have cycle lengths of up to 90 days, and yet I’m out of luck.”

Delano’s piece also points out that period-tracking apps also marginalize queer women. One app requires her to input her method of birth control in order to use it; Delano, whose partner is female and who therefore has no need for contraception, selected ‘None.’ Not using any birth control would surely raise ‘risky’ red flags, per any heteronormative risk assessment an insurer might make. This opens up the possibility of higher health care costs for women who don’t fit society’s narrow definition of womanhood.

Ultimately, what seems to be clear is this: the more companies that have access to your data, the more companies will have access to your data. This perpetuates flawed ideals, services and experiences, and ultimately, discrimination. It’s a dehumanization that feeds femtech’s and social media’s historical disregard for users’ data privacy –which ultimately boils down to disregard for the users themselves.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

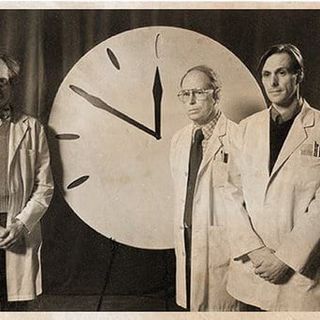

The Doomsday Clock Shows We’re Two Minutes Away From World Destruction