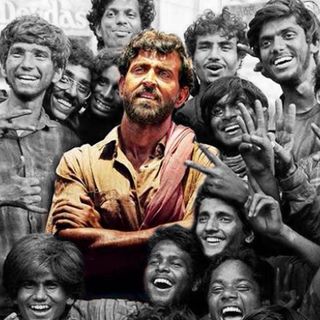

Peripheral Vision: The Vada Pav Seller

“From being a beggar to a businessman — the journey has been long, but happy.”

Our series, Peripheral Vision, explores the untold stories of people we encounter on a daily basis.

I’m Janardhan Vishwakarma Lohar, and I think I’m 60; I don’t know my exact age because I’m not educated.

I also don’t know when I landed in Mumbai exactly. If I had to think about it, it would be approximately 10 years before Indira Gandhi was assassinated [in 1984].

I had a fight at home. I wanted just two paise, but my mother refused, saying when we didn’t have money to eat, how could I ask for money for anything else? I got angry; I was frustrated with poverty. So, I left home without telling anyone. I went to the station and hopped on to the next train. We had steam locomotives then. They were so fascinating that people would come to the station just to look at them. I didn’t have money, but I went ahead and sat near the washroom. The ticket checker came but didn’t say anything because this is what the poor would do — take the train, sit near the pantry or the washroom, and travel.

It took me a week to reach Mumbai from my village, Ghazipur, a little beyond Banaras in Uttar Pradesh. I had nowhere to go, so I started begging. I lived on alms for a few days when a restaurant owner in Santacruz spotted me and asked if I’d like to learn to cook. I didn’t have an option, so I said yes.

For the next five years, I worked in his restaurant, serving guests and learning how to make sweets like pedas, gulab jamuns, jalebis, dosa, samosas and vada pav. The owners said I picked it up quickly and were very happy with my progress.

Related on The Swaddle:

Peripheral Vision: The Watchman Guarding Your Home

When I thought I had made enough money to sustain myself, I called my family to Mumbai. First, my wife came alone and left our three children with my mother. She insisted I open my own vada pav stall. I hesitated initially, but I have to admit that I liked the idea. I had three children to look after and my dream was for them to study in Mumbai.

So, every day after working at the restaurant, I’d go and do my own research about where I could open my stall and where I could source the materials from. Then, I started working on the costing and realized it was actually a financially beneficial idea.

I opened one close to where my chawl is. There weren’t any good vada pav walas there. It took me a few days to procure a stove and utensils; I got started as soon as I had them. The first few days were tough; I had no idea how many vadas or how much chutney to make, or how many pavs to order. I figured all that out in a couple of days, and my business started rolling.

When I first started out, I remember selling a vada pav for six paise. Now I sell it for Rs. 13.

I start my day at 6 a.m., get into the shop and finish prepping by 9 a.m.. I work alone at the shop until 10 p.m., although my wife helps me make the chutneys and masalas at home and boil and peel the potatoes.

I owe her whatever I am today. She pushed me into opening my own stall, and it’s because of her that two of my children are in the 10th and 12th grades in good municipal schools in the city. What would we have done back in the village? They don’t know what they want to become yet, and that’s fine … at least they are studying hard. I know they’ll pass with really good grades in their board exams, as well.

They know how hard I work. I don’t take days off. My father-in-law died recently, and I couldn’t go back because I have a daily wage to earn. If I lose out on even a day’s income, I will have no rent to pay for my six by 10 chawl.

Related on The Swaddle:

This Is My Family: ‘We Let Our Son’s Boyfriend Live With Us’

The sun, the rain — nothing can stop me from running my shop. I’m here when it rains heavily, ready to feed without charging a single penny or just offer shelter in my little shop to anyone who needs it. I even take special requests like mirchi bhajiya or samosa chat simply because people crave it more during the monsoons. It depletes my raw material, but nothing makes me happier than seeing smiling customers.

I can say I am somewhat successful because I have a lot of repeat customers. From school kids to office-goers, everyone enjoys my food.

This job is a lot of hard work; for me to be a person from UP selling a Maharashtrian dish is a lot of responsibility, but I enjoy it. I make about Rs. 2,500 a day with which I pay rent for my chawl, school fees, run a house, and also send some back home in my village.

The best part about this job is that it serves as an equalizer. From a person who’ll get off the car to buy a vada pav, to a beggar — everyone will come to my shop and eat and drink chai from the same cup. I could’ve continued being a beggar; my children would’ve been beggars. But I’m a businessman who has educated them. I will continue to work hard for as long as I can, despite all the hardships, hard work and compromises I have to make to stand here all day feeding people.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. As told to Anubhuti Matta.

Anubhuti Matta is an associate editor with The Swaddle. When not at work, she's busy pursuing kathak, reading books on and by women in the Middle East or making dresses out of Indian prints.

Related

Global Lost Wallet Experiment Shows Humans Choose Good Over Greed