Phone Stress Is a Real Thing and It Might Be Shortening Our Lives

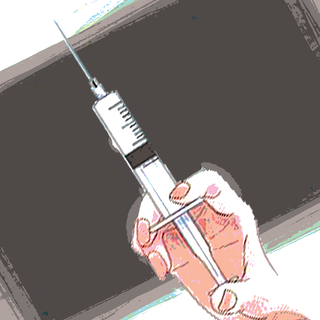

Consistent spikes of cortisol, as from constant connectivity, are known to harm long-term health.

It’s been reported for years that smartphones are bad for us — their apps are addictive; their blue light keeps us from getting enough sleep. But evidence is mounting for a new threat these constant companions pose: the chronic stress we experience from their mere presence contributes to a whole host of health problems, all of which could shorten our lives.

“Your cortisol levels are elevated when your phone is in sight or nearby, or when you hear it or even think you hear it,” David Greenfield, professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine and founder of the Center for Internet and Technology Addiction, told the New York Times in a recent report on this topic. “It’s a stress response, and it feels unpleasant, and the body’s natural response is to want to check the phone to make the stress go away.”

Cortisol is a hormone that, in the right amount, can keep you alive. It’s part of the body’s fight-or-flight reaction to stress. But when cortisol spikes occur regularly, or remain consistently high, the body enters a state of chronic stress. Chronic stress has been linked to everything from memory problems and cognitive difficulties, to cardiovascular damage, low immunity, diabetes and other conditions associated with poor health and shortened life spans.

It’s a reaction you might not even be conscious of — “the ‘mere presence’ of a cell phone may be sufficiently distracting to produce diminished attention and deficits in task-performance, especially for tasks with greater attentional and cognitive demands,” concludes a 2014 study of the phenomenon. In other words, just having a cell phone on you requires the diversion of some of your energy toward ignoring it, making it more difficult for you to focus — a form of cognitive stress known as directed attention fatigue.

Related on The Swaddle:

Have You Been Phubbing People?

Indians would appear to be highly vulnerable to phone-induced stress. They spend anywhere from 90 to 130 minutes daily on their phones, according to Nielsen data cited in a 2018 Financial Express report. In that time, most use anywhere from six to 10 apps, according to an analysis of 1,000 Indian smartphone users by techARC, an analytics and consulting firm. And during the rest of the day, presumably, notifications are pinging from the additional 41 to 45 apps the average Indian has installed on their phone, but may not use daily — not to mention, of course, good, old-fashioned texts and phone calls.

“The result,” writes Catherine Price, the author of The New York Times article examining the phenomenon of phone stress more broadly, “as Google has noted in a report, is that ‘mobile devices loaded with social media, email and news apps’ create ‘a constant sense of obligation, generating unintended personal stress.'”

But most of us don’t realize the toll. “Nobody comes to a therapist saying ‘I have stress because of my phone,'” says Sadia Saeed, a psychologist and founder of Inner Space Counseling in Mumbai. Yet, its very common for her to treat patients for whom the presence and/or compulsive use of the phone is a source of stress, she says. Working with these clients in therapy is about getting them to realize the stress of their phone and habits, and how it compounds whatever problem they are aware of. Saeed says she sees this most among middle- and upper-management professionals. “They end up being connected even when they don’t need to be connected,” she says. “No one is asking ‘Do I really need to check it now?’”

So, how to fix it?

Ultimately, having a phone on you is unavoidable in this day and age. Which likely means we’re all destined for some degree of divided attention and cognitive stress. What we can control, however, even if it seems compulsive and outside of our control, is our active use of phones.

The first thing Saeed does with these clients is help them establish an awareness of when their attention is pulled by their phones unnecessarily, and then build the discipline to resist it. She advises some amount of ‘digital detox’ each day, when the phone is not carried.

Related on The Swaddle:

Phone‑Addicted Teenagers Are Unhappy — But Is It Because of Screen Time?

In a new study of compulsive phone use from the University of Washington’s Information School, in the U.S., participants, both young and old, proposed an ideal ‘lockout’ mechanism they said they wished would kick in after a certain amount of use. But such apps already exist — Flipd, for instance, is an app for both iOS and Android, that locks the phone for a set period of time decided by the user, with no take-backs; even restarting the phone won’t unlock it. Which suggests to the study authors that while apps that limit distraction might be useful, they might not be the whole solution to reducing the stress of having your phone around.

“If the phone weren’t valuable at all, then sure, the lockout mechanism would work great. We could just stop having phones, and the problem would be solved,” Alexis Hiniker, one of the study’s co-authors and an assistant professor at the university, said in a statement. “But that’s not really the case.”

“The solution is not to get rid of this technology; it provides enormous value. So the question is: How do we support that value without bringing along all the baggage?” he continued.

Ultimately, Hiniker’s team concluded, the way to combat phone stress isn’t to forcibly limit time spent on our phones, but to devote that time to the digital activities we find meaningful — a WhatsApp-meme-fest with a best friend, or working one’s way through a shared e-book list with a family member.

“People have a pretty good sense of what matters to them.” Hiniker said in the statement. “They can try to tailor what’s on their phone to support the things that they find meaningful.”

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

FDA Approves Dengue Vaccine, But With Restrictions