Poetry Has The Power to Move Us, So Why Is It Still Taught In Such a Boring Way?

Poetry’s power can move us, and yet we learn poetry by analyzing it like prose, rather than emotionally engaging with it as art.

Poetry is powerful. A combination of rhythmic verses can take us by hand and lead us to epiphanies, it can teach us how to love and how we’d want to be loved, it can serve as a moral parable, and it can mobilize a nation’s people to protest. Poetry is powerful, because at the correct rhythm and cadence, it can play our emotions up and down like a trained concert pianist. Yet, learning poetry in school remains excruciatingly boring, as it completely eschews all of the powerful emotional connections involved that make poetry valuable.

Neuroscience backs up our emotional engagement with poetry. In a study, scientists observed that individuals who listened to poetry experienced visible goose bumps — almost as if they were listening to their favorite songs or film dialogues. Listeners were also able to anticipate emotional arousal during the beginning of the poem, and this experience was similar to unwrapping a chocolate before biting into it. The same emotional arousal also occurred towards the end of the poem — even when 77% of the study participants had never listened to the poem before. A poem is crafted with emotional crests and troughs, and engaging with them is pivotal to understanding and truly connecting with them. This, of course, is heightened when poetry, like music, is heard.

Poetry is, in a way, a performance art form. To recite poetry effectively and to have freedom to play around with the enunciation, rhythm, and style of a verse, one must know a poem by heart. However, many people don’t get to develop that relationship with poetry because their introduction to poetry was a tedious experience. While working on Cambridge’s ‘Poetry and Memory Project,’ education researcher Dr. Debbie Pullinger and her collaborator David Whitley realized that enforcing memorization and recitation puts children off poetry, sometimes even for life. There was a gap between what poetry could provide and what students took away from it, and that gap happens to be the way poetry is taught — as a dry, emotionless means to a curriculum’s end rather than an art form children could enjoy.

Related on The Swaddle:

Here’s How Protest Slogans Help Grab the Attention of People, Those in Power

This isn’t a recent phenomenon. In Catherine Robson’sHeart Beats: Everyday Life and the Memorized Poem, she writes that 19th century English professors taught poetry to purge speech mannerisms and accents common to ‘lower class people.’ Plus, the choice of poems that students were made to memorize was not well-thought out, and heavily depended on nationalism, what editors of literary textbooks chose to include, and even random happenstance. Both then and now, language education expects students to merely internalize poetry’s importance just because, rather than guiding them through how they can interpret and emotionally engage with its meaning.

According to research published in the journal Changing English, a reason for this is because the importance of teaching poetry is often grouped along with the importance of teaching literature. Therefore, poetry is taught like literature — it is only analyzed and dissected rather than performed. In a poem titled Introduction to Poetry,Billy Collins wrote,

“But all they want to do

is tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.”

Analyzing poetry is important to how one understands it, but researchers advocate for a touch more — allowing students to form their own personal emotional connections and understanding of a poem by hearing it/speaking it out loud. Dr. Pullinger says, “Hearing a poem without sight of the text can be a revelation. Our mind is free to attend to tasks other than decoding and our mind’s eye is free to roam. Putting the book down is a bit like taking the stabilizers off the bike. You may be a bit wobbly at first, but only then can you really feel the way the bike is moving over the surface; only then can you find your balance.”

Related on The Swaddle:

14‑Year‑Olds Running Slam Poetry Workshops Prove Arts Education Shouldn’t Be an Afterthought

Memorizing and reciting poetry is not merely an art form — it helps boost cognitive abilities. Memorization’s major benefit is that it builds a referencing power that significantly aids critical thinking and analysis. Memorizing poems, according to Susan Wise Bauer, author of The Well-Educated Mind: A Guide to the Classical Education You Never Had, helps children understand language syntax, patterns and word memory. Reciting poems, on the other hand, teaches young children rhythm, pronunciation, and a deeper, emotional connect with literature. One can infer that memorizing a poem allows a person the freedom to experiment with and emotionally connect with a verse in a way that reading cannot.

If poetry’s major task is to make people feel, then those feelings are vital to how people learn to understand and enjoy poetry. In an address to the Yale Political Union, poet Meena Alexander said, “In a time of violence, the task of poetry is in some way to reconcile us to our world and to allow us a measure of tenderness and grace with which to exist.” And there’s no way to reconcile with both verse and the world if we don’t understand what we feel about it.

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

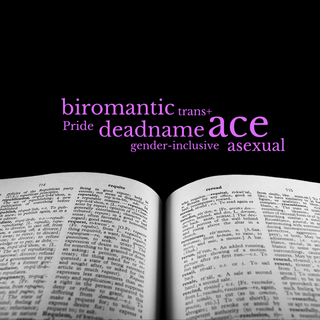

Dictionary.com Adds LGBTQIA+ Terms Such as ‘Deadname,’ ‘Biromantic’ in Biggest Update Ever