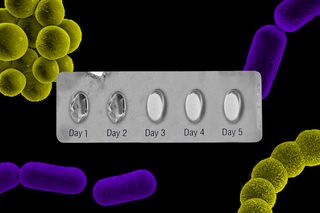

We Now Know Full Courses of Antibiotics Can Foster Resistance. So Why Are Patients Still Told to Complete Their Course?

Research shows that for most common infections, long exposure to antibiotics just creates more opportunity for bacteria to become resistant.

Amid the global Covid19 outbreak, India is the quiet epicenter of another, overlooked, but far more deadly pandemic: antibiotic resistance. The country has some of the highest antibiotic resistance rates in the world. Most concerningly, its incidence of colistin resistance — that is, resistance to a drug of last resort, used only when all other antibiotics have failed — is increasing.

In India, myriad factors have contributed to one of the worst antibiotic-resistant environments in the world: Pharmaceutical pollution of major waterways; increased antibiotic use in livestock rearing. But the focus of blame has often been on patients — individuals who don’t complete the full course of antibiotics as prescribed allow antibiotic-exposed bacteria to survive and strengthen. Others self-medicate, exposing bacteria unnecessarily to antibiotics and thus fostering resistance. As recently as 2016, the World Health Organization offered the following guidance: “always complete the full prescription, even if you feel better, because stopping antibiotics early promotes the growth of drug-resistant bacteria.”

But over the past decade, research has accrued proving precisely the opposite: antibiotic resistance is more likely to develop the longer a patient takes antibiotics. For most infections and most cases, patients can and should stop taking medicine once their symptoms resolve. Yet doctors’ prescriptions, by and large, remain wedded to an arbitrary and outdated definition of ‘full course.’

Overkill: When Modern Medicine Goes Too Far traces these lengthy antibiotic courses back to the discovery of penicillin, which was administered in much smaller doses than today’s more-potent medications and thus required longer treatment schedules to be effective. Today, a full course of antibiotics is typically defined as five to seven days, or multiples thereof. But this definition is influenced more by the metric system and the length of a week, than by watertight research, says Overkill author Dr. Paul Offit.

“When you have symptoms, it’s because of your response [to bacteria],” Dr. Offit explains. “You don’t have symptoms because of the bacteria per se, you have symptoms because of your response to the bacteria. So, when those symptoms abate, then you can argue reasonably that there is no bacteria reproduction.” And therefore, no need to continue an antibiotic.

When symptoms stop, when tests are clear — “why can’t that be the marker for when to stop? Your immune system is saying you’re done; stop,” he says. He notes exceptions, like tuberculosis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis can hide inside specialized immune cells and lay dormant, becoming active again in the future; a full and often long course of antibiotics is critical to making sure the infection is eradicated in this inert state to avoid relapse. But in most common cases — sinusitis, urinary tract infections, appendicitis, skin infections, even pneumonia — the longer exposure to antibiotics only gives bacteria more opportunity to become resistant.

Dr. Offit, a U.S. pediatrician who specializes in infectious diseases, immunology, and virology, is not some malcontent, challenging the medical establishment from its fringes. Ten years ago, researchers established a link between prescribing practices — especially length of treatment — and antibiotic resistance. And in 2017, a group of doctors and scientists published a paper in The BMJ, a well-respected, peer-reviewed medical journal, calling for medical practitioners to stop the standard advice to complete a full course of antibiotics.

The same year, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) issued its first antibiotic prescribing guidelines. In its 2019 update to the same, the ICRM still lists standard treatment durations for common infections in five- to seven-day increments (or multiples thereof) — but now includes this advice at the beginning: “Duration of therapy should be optimized to minimum possible to reduce [the chances of resistance developing].”

Related on The Swaddle:

Indian Newborns Are Dying of Antibiotic‑Resistant Infections

But minimizing therapy — stopping antibiotics early or avoiding them altogether — could feel like withholding health care. This goes against the ethos of the medical field, the purpose of which is to provide health care. It’s a fine line to walk — reflected in the WHO’s updated 2020 guidance on full antibiotic courses: “Feeling better, or an improvement in symptoms, does not always mean that the infection has completely gone. Your doctor has had years of training and has access to the latest evidence – so always follow their advice.”

This caginess reflects the very real ramifications on doctors who cut short an antibiotic treatment, even if it’s the right thing to do. “People are generally sued for what they don’t do, rather than what they do do,” Dr. Offit says.

Even in cultures less litigious than the West, physicians must balance giving the care the patient wants and the care the physician thinks or knows is best. In India, physicians may prescribe a full course of antibiotics because a follow-up consult or testing often isn’t possible to determine whether stopping treatment is advisable. Or they may prescribe antibiotics for infections that are not bacterial but viral because patients want treatment and do not understand antibiotics have no effect on viruses. In both cases, it’s the patients’ needs or wishes driving the prescription, rather than the doctors’ knowledge or best practices. Reports abound of violence against physicians — research by the Indian Medical Association suggests up to 75% of physicians have experienced some kind of violence at work — perhaps explaining some physicians’ decision to do something, and for longer, rather than do nothing, or cut short a treatment.

“What many times happens is because there is an expectation from a patient, when they visit a prescriber, if the prescriber doesn’t prescribe them [medication], that patient’s expectations aren’t met. That is one reason by prescribers are forced to do something,” says Dr. Habib Hasan Farooqui, an associate professor at Indian Institute of Public Health-Delhi, Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), who specializes in pharmaceutical economics and infectious disease epidemiology. Dr. Farooqui is the lead author of 2019 study exploring antibiotic prescription practices within India’s private health care industry.

Even when physicians are moved to prescribe antibiotics because of a clinical diagnosis, they often choose to stick with what they know. In Offit’s opinion, one of the main drivers of unnecessarily lengthy courses of antibiotics is inertia — doctors who are more comfortable adhering to their own patterns rather than to the latest guidance.

“I just think most physicians, especially older physicians say to themselves, ‘Well, this works for me, so I’m not going to change,’ because they don’t really embrace, in a manner that they should, that they’re doing harm,” Offit says.

Prescribing a full course of antibiotics is seen as “the conservative thing to do – just in case,” he adds. “But if you’re creating resistance, and antibiotics have side effects, and you can cause bacterial overgrowth in the intestines, then it’s not the conservative thing to do – it’s the radical thing to do. I just think it’s very hard to change thinking.”

In India, the bigger, better-resourced, urban, teaching and research hospitals, as well as the medical schools, have managed to shift thinking around antibiotics, erring on the side of the advised short courses and aware of the resistant strains trending among their communities, Dr. Farooqui says.

Related on The Swaddle:

There Are Human Drugs in Your Drinking Water Supply

Outside of these institutions and areas, however, it’s a different and very complex story. It’s not just individual inertia keeping outdated or inappropriate antibiotic prescribing practices in play, but also the absence of a culture of continuing medical education, especially among the fringes of medical practice – traditional healers who incorporate modern medicine without proper training, for instance, and pharmacists who give out antibiotic samples. These groups are among the biggest prescribers of antibiotics in India. “They need to be brought into the net of continuing medical education and rational prescribing practices,” Dr. Farooqui says.

Dr. Farooqui says many strategies are underway to accomplish that. But such integration will be a long process and perhaps require time the world cannot spare. In the urgent present, cases of antimicrobial resistant infections have already been documented among India’s Covid19 patients. And unlike the Covid19 pandemic, for which several vaccines are on the horizon, the antibiotic resistance pandemic has no likely end; despite reports of new breakthroughs or obscure, rediscovered treatments, nothing is close to offering the level of protection against infections that antibiotics did during the 20th century.

“In 2019, the UN Interagency Coordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance warned that by 2050, antibiotic-resistant diseases could cause 10 million deaths each year and can cause damage to the economy so catastrophic that, by 2030, antimicrobial resistance could force up to 24 million people into extreme poverty,” write the authors of a paper recently published in The Lancet. They go on to warn indiscriminate antibiotic use for bacterial co-infections in Covid19 patients could be worsening the overlooked pandemic of antimicrobial resistance.

“We can get on top of this [Covid19] pandemic,” Offit says. “But don’t ignore this other thing in the meantime, because that’s going to be with us much longer.”

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Why Some People Find Cleaning Therapeutic