Anti‑NRC‑CAA Protest Is Changing What Pride Looks Like

“It cannot just be a celebration by upper-class and upper-caste gay men anymore.”

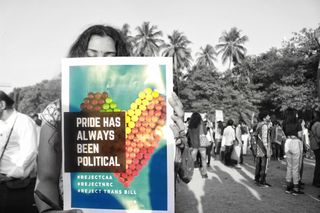

On Feb. 2, 2020, Mumbai held its annual Pride event — except it didn’t look like the Pride of years past. Relegated to Azad Maidan’s vast but enclosed space, Pride organizers Queer Azaadi Mumbai (QAM) were denied police permission to hold the event at its usual venue outside August Kranti Maidan for fear of Pride-goers raising anti-NRC-CAA slogans. Upon the venue change announcement, many hopeful attendees took to social media to condemn QAM’s compliance, asking: what is Pride, if not political?

Many took the censure aimed at Pride organizers one step further: they brought anti-NRC-CAA signs to Pride nonetheless, and sloganeered for azaadi, for detained activist Sharjeel Imam, for the rights of minority groups affected by the NRC-CAA. Now, 50 of them are being charged with sedition.

QAM, which purports to make Pride “an expression, a voice, a celebration, and a platform to ask for equal rights of these individuals,” according to their weblog, released a statement separating themselves from the protestors, making clear they had nothing to do with the more radical activism within Pride — activism, incidentally, that sought to use the Pride platform to ask for equal, if not uniquely queer, rights. “We completely dissociate ourselves from and strongly condemn the abrupt radical slogans in support of Sharjeel and/or any other slogans against the integrity of India at the gathering,” said a statement QAM released on social media. “We feel that irresponsible sloganeering under the garb of dissent not just affects the safety of individuals who signed the permission but QAM as an entity,” adding they strongly condemn anything that goes against the principles of the Indian Constitution and law.

QAM’s motivation for releasing this statement is being questioned by many queer activists who believe the organization should have backed those being charged with sedition. A generous reading of the QAM statement assumes a protective instinct toward Pride-goers, the event, and the organization. But critics say QAM’s move has exposed and accentuated broader, hidden fault lines in the politics of those who have purported to be the face of the city’s queer population — mostly upper-class and upper-caste cis gay men, whose political interests, they say, seemed to dry up after the repeal of Section 377 and failed to expand to advocate for more diverse queer bodies, especially spanning caste lines. Sloganeering against the NRC-CAA, which predominantly affects transgender people, Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi people, and Muslims, should be directly relevant to Pride and what it stands for, critics say. (QAM did not respond to multiple requests for comment by the time of publication.)

On social media, queer critics called the organization cowardly, operating in the interest of a select few, and not necessarily interested in representing diverse factions within the city’s queer population. But they also made it clear the NRC-CAA dissent at Pride wasn’t the catalyst for such a betrayal to happen; it was merely a symptom of the exclusion and lack of intersectionality Mumbai’s marginalized queer groups have been facing for a long time.

“There has been very limited representation of the issues that affect trans people, or religious minorities within Pride. We have to understand Pride cannot look at simply LGBTQIA+ issues alone; we have to look at how those issues intersect with trans rights, or the rights of other minorities,” Pride-goer and student M., 21, said. “It cannot just be a celebration by upper-class and upper-caste gay men anymore.”

M. added that while they were disappointed by organizers’ push to keep Pride relatively apolitical under pressure from the police, the presence of activists raising those slogans anyway signaled a new direction for future Pride movements — away from exhibition art and toward intersectional politics. Another Pride-goer, D.N., 53, added, “I can’t understand how anybody can claim to keep politics away from Pride; we are still not equal here, so it has to be political,” adding protests are the need of the hour and Pride has to be one way to do it.

Related on The Swaddle:

What a Transgender-Friendly Health Care System Would Look Like

Many critics, however, don’t see Pride being able to entertain these issues unless the organizational status quo changes. “Every year, there is at least one angry post about QAM’s undemocratic and high-handed ways, and every year a small group of people attempts to perform one or other kind of ‘reclamation’ within Pride. Every year there is an active and absolute silencing enforced by QAM. And every year the QAM finally absorbs and appropriates the narratives of those whom they attempt to silence, to claim inclusion,” trans rights activist Esvi Anbu Kothazham writes in “A Position Against Mumbai Pride” on Medium. Kothazham advocates not for reclaiming or reforming Mumbai Pride from within — that hasn’t worked for almost a decade, they write — but for dismantling the monolith it has become and starting anew to create a more inclusive, intersectional movement that spans caste, class, and religious lines.

As the NRC-CAA dissent brings society as a whole toward a tipping point, it’s important to ask — is Pride supposed to represent a space inclusive of all voices and experiences seeking equality, or is it supposed to simply be a symbolic event that preserves its celebratory aspect, perhaps at the cost of intersectionality? QAM seemingly showed they’re ascribing to the latter, but with the current wave of protests only getting stronger and more widespread and inclusive, it’s clear this approach won’t be sustainable for long. When symbolism becomes superficial, it hurts marginalized groups that need to become political by virtue of them being in a society that politicizes their existence. Not welcoming these groups, and the issues they’re fighting for, under the larger purview of Pride not only digresses from its original purpose but paints a bleak future for itself. Pride is changing; it’s time to change with it.

Rajvi Desai is The Swaddle's Culture Editor. After graduating from NYU as a Journalism and Politics major, she covered breaking news and politics in New York City, and dabbled in design and entertainment journalism. Back in the homeland, she's interested in tackling beauty, sports, politics and human rights in her gender-focused writing, while also co-managing The Swaddle Team's podcast, Respectfully Disagree.

Related

One in Every Seven Tweets About Indian Women Politicians Is Abusive: Study