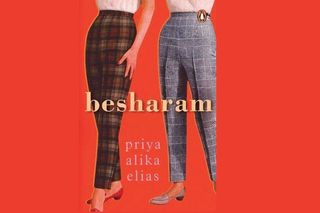

Priya Alika Elias’s ‘Besharam’ Dismantles the Trope of the Good Indian Girl

“This vision of the Indian woman that we create is entirely imaginary,” Elias writes.

People spend a lot of time thinking about Indian women having sex. This much is undeniable. There is a curious eroticism even to the good Indian woman, submissive and silent. Boys all over India masturbate to ‘aunties’ (aunty being one of the most popular search terms in India). Neighbouring aunty. MILF. Bhabhi with young brother-in- law. Stepmother with stepson. The women in these videos have nothing in common with the glossy, perfect porn stars on Brazzers. Instead, they look much more like the tired women we see in our kitchens, wiping one atta-smeared hand across their foreheads. Perhaps, it is precisely for that reason that they are more popular with young, hot-blooded Indian men.

And yet we stubbornly and steadfastly refuse to talk about sex. To bring it into the public domain. Sex is something that happens quickly under bedsheets, or covertly in the afternoon while the children are playing and you’re pretending to have your afternoon nap. It happens after marriage for purposes of procreation, because those things are not in our culture.

The only people who talk about sex are men (often making what they call ‘non-vegetarian jokes’ to other men). Growing up, I never encountered raucous women like the ones on Sex and the City, who spent Sundays at restaurants discussing their partners’ sexual fortitude. I didn’t even know what counted as sexual activity, or which types of sexual activity could lead to pregnancy. (I didn’t have one of those glossy American books called ‘Your Body and You’ to explain those mysterious dynamics, those hormonal shifts.) Could you get pregnant from kissing? In my confused adolescent imagination, you could.

‘You’ll have to be careful now,’ my grandmother told me when she saw the bloodstains on my bed. (I had just awoken from a sweaty nap, and I regarded them with wonder— nobody had told me about periods.) ‘You’re a woman now, and you must cross your legs when you sit, and not run around with the colony boys playing cricket. Those days are over.’

Although I have a younger brother, I understood as if by instinct that he would receive no such warning. Oh, he would go through the rituals of puberty—the first sign of stubble on his cheeks, the deepening of his still- babyish voice—but there was nothing in his future that had to change. Maybe this is the saddest thing about being a woman: attaining womanhood means learning what we are forbidden to do. Attaining manhood means learning what you are capable of.

When I first read ‘Girl’ by Jamaica Kincaid, I shivered with recognition. Although Kincaid was writing of an entirely different cultural context—the island nation of Antigua in the 1980s—I knew that the contours and textures of her world were similar to mine. ‘On Sundays, try to walk like a lady and not like the slut you are so bent on becoming,’ intones the mother figure in a mournful voice to the carefree young girl who is the subject of the short story. ‘Don’t squat down to play marbles—you are not a boy, you know [ . . . ]’

For the girl, growing up is an act of learning. She is taught how to cook, how to clean, and how to be a woman. The boy, meanwhile, plays cricket in the garden. His world is still unlimited.

I thought of the Malayalam proverb: ‘Ila mullil veenalum mullu ilayil veenalum, ilaykanu dosham’ (whether a leaf falls on the thorn or a thorn on a leaf, it is the leaf that will suffer). It is us, always us, who must suffer. It is a proverb repeated to wanton women to remind them of what can happen.

The very word ‘shameless’ is deeply gendered. How many men have you heard being called shameless? It may be jokingly applied, but it is difficult to think of a man who has been adjudged ‘besharam’ in all seriousness. No no, besharam is for women who want things, who are fearless about voicing those wants, who are frankly unapologetic about it.

In such a context, with such a childhood, how will women speak about sex or desire? If the Internet is to be believed, Indian men are absolutely stuffed to the gills with desire. ‘Nice bobs mam’, ‘very nyc dear’, ‘kiss to u’ are the comments they leave on popular female celebrities’ pages. They message women they’ve never met on Facebook, asking if they can ‘make frandship’. This is so ubiquitous as to have become a meme: even Americans know that ‘show bobs and vagene’ is likely to have come from a horny man sitting in front of a computer somewhere in India. These are the men so desirous that they keep and share logs of WhatsApp numbers that they believe belong to women.

But, where are the women?

Good girls don’t. The ideal Indian woman is clearly Sita, the heroine of the Ramayana. Sita is beautiful, modest and virtuous in every breath. She is faithful to a husband who nonetheless discards her. In the most popular version of the story, she suffers an unfair fate without complaint—and there is never any question about her chastity. There is no question of her seeking sexual pleasure for her own sake. This vision of the Indian woman that we create is entirely imaginary. And it is her counterpart in the Mahabharata—Draupadi—who excites us.

Five husbands! Which straight woman cannot confess to getting a faint thrill while thinking of having five husbands to satisfy her manifold and often conflicting desires?

I imagine that some of the girls I know might want to have five boyfriends. Some of us might fantasize about having sex with a different man each night. Some of us want to have sex each night. I remember Cheryl, who I went to school with, who used to draw explicit pictures of Archie, Betty and Veronica in the corner of her notebook.

‘They’re smooching,’ she would tell me with glee as she flipped the pages to show me. ‘They’re smooching and they like it. And then they’re going to have sex for days and days and days. They’re going to get married and go on a honeymoon, and have sex for days.’

Oh, yes. We want to have sex.

This is an excerpt from Besharam: Of Love and Other Bad Behaviours, by Priya Alika Elias, available now through Penguin Random House India.

Priya Alika Elias is a lawyer and a writer. Elias has written for New Republic, VICE, Gawker, Buzzfeed, Teen Vogue, Outline, Toast, McSweeney's, Vox, Ask Men, Firstpost and Outlook. Her writings cover a range of subjects, from feminism, race and mental illness to dating and music videos, while her essays explore universal questions through the lens of pop culture.

Related

Public Database Lists Personal Details of 1.8 Million Chinese Women, Including Whether They’re ‘BreedReady’