Rich and Poor Have Similar Life Expectancies, Says Comprehensive Data Study

But the data was gathered in a country with excellent public healthcare and education.

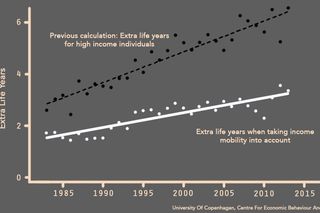

One might assume that rich people’s life expectancies would far out-pace poor peoples’ expected lifespans, because of education, awareness about disease, access to healthcare and healthier food, and many other factors. In fact, one of the most well-known studies out of Harvard, from 2016, specifically confirmed this in in the US context. Now, a new study out of Denmark challenges that assumption, and asserts that there is actually very little difference between the life expectancies of the rich and poor. The previous data, the authors of the study argue, was excluding one key point: that people who were rich can become poor, and people who were poor can become rich.

New research results, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), challenge the idea that the rich and poor experience a large difference in life expectancy. Danish economists Claus Thustrup Kreiner, Torben Heien Nielsen, and Benjamin Ly Serena from the University of Copenhagen (UCPH) have found a way to calculate life expectancies across income classes, specifically taking into account the fact that there is mobility across those classes.

All previous research on life expectacies and income levels had been predicated on the assumption that people stay within those levels. In reality, however, over a ten-year period half of the poorest people actually move into groups with better incomes and likewise, half of the rich leak down into lower income classes. The mortality of those who move to a different income class is significantly different from those who stay in the same class.

When they used their formula to calculate Danish life expectancies, the results were stark:

When accounting for income mobility, life expectancy for a 40-year-old man in the upper income groups is 77.6 years compared with 75.2 for a man in poorer groups – a difference of 2.4 years. For women the difference between high and low-income groups is 2.2 years. However, without taking the income mobility into account the life expectancy difference was twice as big – around five years – for both men and women.

“Our results reveal that inequality in life expectancy is significantly exaggerated when not accounting for mobility. This result is quintessential not only for our understanding of one of the most important measures of inequality in a society, namely, how long different groups can expect to live. But also by mis-measuring this type of inequality, we get to misleading conclusions about the cost and benefits of public health programs,” says professor Thustrup Kreiner.

While this result is heartening, it’s important to note that Denmark is specifically known for its superlative public education and healthcare systems. In a country where there is less inequality in awareness and access, it stands to reason that there would similarly be less inequality in life expectancies. But in countries where excellent, or even adequate, medical care is one of the clearest benefits of wealth, these results would likely not hold. What this study might indicate, for a country like India, is how powerful public healthcare and education programs can be for extending the lives of its citizens.

Related

Noise Exposure Increases Heart Attack Risk, Study Finds