Scientists Are Developing a ‘Revolutionary’ Test That Detects 4 Cancers in Women

Routine smear tests could identify ovarian, breast, womb, and cervical cancers — which would be a “game-changer” for women’s health.

Imagine if a visit to the doctor for a routine cervical screening could help identify the risk of developing other gynecological cancers too. That seems to be the end goal for some scientists, who are currently developing a single test to identify ovarian, breast, endometrial, and cervical cancer at an early stage. Not only that, the test could also identify genetic markers that show a person’s risk of developing them in the future. In other words,early and regular screening could help stop these cancers even before they start.

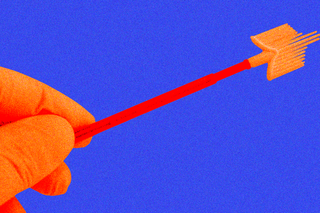

The researchers published some of their findings in the journal Nature Communications on Tuesday. Two individual papers outline how this testmay work: the women’s cancer risk identification test (WID-test) could analyze cervical cells’ genomes from a routine pap smear to spot ovarian and breast cancer — or even gauge the likelihood of someone developing it through genetic signatures.

The results about the accuracy of theWID test for predicting womb and cervical cancer are still pending. But if larger studies confirm the test’s efficacy, a routine pap smear test that women already use could become a screening tool for the future.

“This could create a step-change in screening for key cancers – not detecting them early but preventing them from developing,” said Athena Lamnisos, the chief executive of the Eve Appeal, which is funding the research with the European Research Council. Some say it could be a veritable “game-changer” for women’s health. Breast, ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers together represent 47% of all cancers in women; while there has been some success in predicting breast and ovarian cancers over the last few years, the survival rate of others remains low.

In their research, the scientists examined cervical smears of almost 2,000 women across 15 different centers in Europe. The categories of participants included those with ovarian or breast cancer, those who had a high suspicion of developing these cancers but were not yet diagnosed, and those who were healthy. According to them the ethnicity of the participants (“white” and “non-white”) didn’t impact the risk assessment.

They fed the data from half of the samples into an algorithm; this could identify a unique DNA signature of something called methylation in the cervical cells. Methylation attaches itself to the DNA and “such changes in cervical cells might be a readout of a patient’s overall history that has an impact on cancer risk,” STAT News noted. Or, as Shelley Tworoger, a cancer prevention researcher at the Moffitt Cancer Center, who was not involved in the study, said: “Looking at methylation is a way we might be able to have an integrated view of the exposures a woman may have had in her life that might affect her cancer risk.”

Eventually, the algorithm was able to correctly assess the category of women at the highest risk of developing cancer.

Related on The Swaddle:

Trial Drug Reduces Recurrence of Genetic Breast Cancer in Women, New Study Shows

“It’s difficult to directly access [the ovaries or uterus] to identify cancer or precancerous lesions, so this might be a good way to identify people at high risk. Most women go in and get Pap smears so we already have this type of sample from women on a very regular basis,” Tworoger added.

The current methods — through ultrasound or blood tests — to detect ovarian or endometrial cancer in many cases don’t catch cancers at an early stage. “At the moment there is no screening test for breast cancer in women under the age of 50. If this test can help pick up women with a high risk of developing breast, ovarian, cervical, and uterine cancer at [a] younger age, it could be a game-changer,” Liz O’Riordan, a breast cancer surgeon, adds. In other words, if women knew they are at higher risk, regular screening and early treatment may lead to better outcomes.

Moreover, using specific epigenetic changes to gauge risk is an interesting strategy in cancer prevention. “If you look at heart disease… the outlook has improved dramatically because we now have markers like raised blood pressure and raised cholesterol which allow us to intervene with preventative measures such as drugs or lifestyle changes. That has to be the model we mimic for women’s cancers,” said Martin Widschwendter, a professor of cancer prevention and screening at Innsbruck University in Austria, and a senior author on the study, back in 2015 when clinical trials were just starting.

One sample predicting the risk of all four gynecological cancers may thus make the testing convenient. “You want to make it easy. If it’s not convenient, then women likely won’t utilize it.”

For most women, early cancer detection, timely treatment of pre-cancerous lesions, or life-saving interventions (such as theHPV vaccination) remains a challenge. Added to this is the extra burden women from low- and middle-income countries face, who are statistically more likely to die due to cancer. “These longstanding [socio-economic] inequities highlight the urgent need for substantive and sustainable investments in cancer control more broadly, including prevention and early detection programs,” a 2017 paper noted.

Arguably, it is a long while before this one single test may be implemented at a large scale for clinical use. Moreover, algorithms are a tricky thing; the dataset, currently including European women, may need to be drastically improved for the test to be accurate on a population-wide scale.

For now, the idea is to understand more about cancer and use this knowledge to bolster treatment and prevention programs. The one big takeaway? Get your cervical screening tests routinely.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Dolo‑650 is India’s Favorite Medicine – and Meme. What Could Go Wrong?