Scientists Discover Tropic‑Like Glowing Fish in the Arctic

The discovery underscores just how much of Earth’s biodiversity is still unknown — and unprotected.

Tropical waters are known for their bright sunlight above and their richly colorful biodiversity below. These two things aren’t unrelated; for the many tropical species that exhibit biofluorescence — that is, the ability to absorb light energy and reemit it as different colored light — the sunlight is crucial. Which is why scientists have never expected to find a biofluorescent species in the Arctic, where so much of the year is spent in twilight and even full darkness.

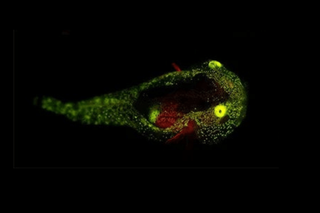

Then swims in Liparis gibbus, or snailfish, an Arctic and far-north ocean species whose youth biofluoresce in not just one color, as is the norm in the tropics, but two. A pair of the red-and-green glowing fish was first spotted about 100 to 200 meters deep during dives to explore the biodiversity off the eastern coast of Greenland in 2019. They have been studied since, and the findings were published this week in the digital research library of the American Museum of Natural History.

“Finding a red and green biofluorescent snailfish on a dive among icebergs at night felt like a moment straight from The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou,” said study author David Gruber, a research associate at the Museum and a biology professor at Baruch College, referencing the 2004 surreal aquatic comedy-parody film.

Related on The Swaddle:

Scientists Discover 30 New Species of Marine Life in the Galapagos

Gruber, and his colleague John Sparks, a curator in the Museum’s department of ichthyology and the study’s co-author, are experts on biofluorescence in fish, having already identified more than 180 other species that can absorb sunlight and reemit it in a different color. Some of these glow brightly in the tropics, but when swimming closer to the Arctic, fail to biofluoresce. One other exception was discovered by Gruber and Sparks: an adult kelp snailfish (L. tunicatus) was found glowing red in the Bering Strait off the Alaskan coast.

Many species on land and on sea biofluoresce, but scientists still don’t understand the purpose behind it. Biofluorescence is a different function than bioluminescence, which is common in the Arctic and deep ocean regions where light doesn’t permeate. Bioluminescence is an internal chemical reaction, much like the one that occurs when a glow stick is cracked, known to help organisms find food and hide from prey. Biofluorescence, on the other hand, is theorized to aid communication and mating, but no one knows for certain if this theory holds.

The glowing snailfish discovery is a reminder of just how little is known about the Earth’s total biodiversity. In addition to making new discoveries about known species, like Gruber and Sparks, there is much scope for the discovery of completely and hitherto unknown organisms. Scientists estimate known species only make up 13-18% of the world’s total biodiversity, according to a new study out of Yale University — this amid an ongoing mass extinction that has put some recently discovered species directly on the endangered list.

“After centuries of efforts by biodiversity explorers and taxonomists, the catalog of life still has too many blank pages,” the Yale researchers write. “Without inclusion in conservation decision-making and international commitments, these [undiscovered] species and their functions may be forever lost in ignorance.”

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Why Do We Have Fingerprints?