Scientists Have Created a ‘Vagina on a Chip’ to Advance Sexual Health Research

This helps test treatments for bacterial vaginosis, study the vaginal microbiome, and bridge knowledge gaps about women’s health.

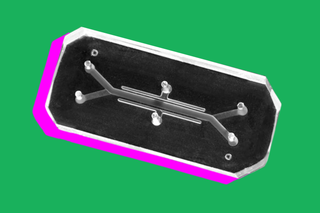

Scientists at Harvard University’s Wyss Institute have created what is considered to be the world’s first “vagina on a chip” – a development that could prove significant in bridging several knowledge gaps on women’s sexual health. According to Scientific American, the chip recreates the unique microbiome of the human vagina using living cells that could help scientists test drug-based treatments for bacterial vaginosis, a common condition that is also notoriously difficult to treat.

“The vaginal microbiome plays an important role in regulating vaginal health and disease, and has a major impact on prenatal health. Our human Vagina Chip offers an attractive solution to study host-microbiome interactions and accelerate the development of potential probiotic treatments,” said first author of the study, Gautam Mahajan.

The study, published last month in the journal Microbiome, outlines how this polymer chip helps understand interactions between fluctuations of the sex hormone estrogen and bacteria, by mimicking how the human vagina responds to both good and bad bacteria. When the researchers introduced the hormone into the chip, they noticed that gene expression patterns changed, revealing the chip was sensitive to hormones which is considered a “critical feature for replicating human reproductive organs in vitro.”

The “vagina on a chip” was made from vaginal epithelial cells donated by two women and is believed to be more realistic than other laboratory models, reported The New York Times. It, therefore, replicates many physiological features of the vagina, revealing the potential of organ chip technology to simulate interactions between the vaginal cells, bacteria and fluids, while also allowing scientists to study the efficacy of various treatments.

Related on The Swaddle:

A New Test Can Analyze Vaginal Microbiomes To Track Pregnancy Risks

As summarized by the Scientific American report, the Vagina Chip demonstrates “how a healthy—or unhealthy—microbiome affects the vagina.” The scientists showed that the growth of Lactobacilli on the chip helped maintain an acidic environment by the production of lactic acid. However, once they introduced another type of bacteria known as Gardnerella, it created an alkaline environment, increased inflammation, and caused cell damage. These are all signs of bacterial vaginosis which is caused by microbial disruptions and affects 30% of women of reproductive age around the world.

Bacterial vaginosis has several repercussions for sexual health – it increases the risk of sexually-trasmitted diseases, including HIV, and also heightens the risk of pre-term delivery in pregnant women, the press release notes. While practitioners rely on antibiotics to treat this condition, it often relapses and can lead to serious complications, including pelvic inflammatory disease and, in the worst case, infertility.

Our limited understanding of the vaginal microbiome has made it difficult to treat bacterial vaginosis. “We don’t really understand how these processes are triggered by bacteria in the vagina or often even which bacteria are responsible… As you might imagine, such a crude understanding of such an important physiological system makes for crude interventions or none at all,” professor Amanda Lewis, who studies the vaginal microbiome, told The New York Times. The Vagina Chip, then, may pave the way for devising effective treatments for not only bacterial vaginosis, but other vaginal conditions as well.

The vagina remains alarmingly understudied, as female anatomy and reproductive health has rarely taken center-stage in scientific research. The pre-clinical study of this organ is further complicated by the vast differences between the human vaginal microbiome and that of animal models. For example, the press release notes that Lactobacilli bacteria makes up 70% of a healthy human vaginal microbiome, but only around 1% in other mammals.

Related on The Swaddle:

Bacterial Vaginosis: a Genital Infection That’s Difficult to Catch

Moreover, other types of cells – such as vaginal immune cells – have not been studied yet, though the bioengineers are planning to integrate these in future research. Apart from testing existing and new treatments for bacterial vaginosis, they are also working on connecting the vagina chip to one that models the cervix, to better represent the female reproductive system. Further, the Scientific American report highlighted another significant next step – one where the team has already begun “personalization” of the chip. This will allow them to study individual vaginal microbiomes by introducing “personal bacterial communities” sourced from vaginal swabs from donors.

Senior author of the study, Dr. Donald Ingber, and his colleagues have previously made a number of such organ chips to simulate the lungs, liver, skin and intestines. However, experts have pointed out the limitations of this technology, including that the modeling of organs in isolation from the body may not provide the full picture. While Dr. Ahinoam Lev-Sagie, a gynecologist at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem hailed the chip as a “great development,” she added, “Real life is much more complicated than the vagina on a chip.” A variety of factors affect the vaginal microbiome, including sexual intercourse, menstruation, hormonal changes and the use of antibiotics.

Despite its limitations, experts remain hopeful that the Vagina Chip could help address the historical neglect that has plagued research on women’s sexual health. Rachel Gross, the author of Vagina Obscura, while speaking about how research and innovation have focused on men’s health, told PBS earlier this year that attitudes of stigma and shame that persist today have their basis in how medical history has favored the male anatomy, viewing women more as “walking wombs or baby machines.” Dr. Ingber also acknowledged that while there is growing recognition that “taking care of women’s health is critical for the health of all humans,” the creation of tools that can enable the study of female physiology are sorely lacking. “We’re hopeful that this new preclinical model will drive the development of new treatments for BV as well as new insight into female reproductive health,” he said.

Ananya Singh is a Senior Staff Writer at TheSwaddle. She has previously worked as a journalist, researcher and copy editor. Her work explores the intersection of environment, gender and health, with a focus on social and climate justice.

Related

Racism, Discrimination Are ‘Fundamental Drivers’ of Global Health Disparities: Lancet Review