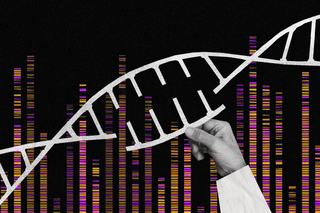

Scientists Have Finally Decoded the Complete Human Genome

The findings have been 30 years in the making, and can offer insights into health and what makes our species unique.

In 2003, researchers accomplished a historic feat: they sequenced 92% of the human genome, the entirety of the human DNA. But huge chunks of DNA — 8%, which are roughly millions of pieces remaining — were still missing; the mission was completed, but not quite.

For nearly two decades now, then, the effort has been to fill these gaps and sequence the genome in its glorious totality. Now, a team of researchers has decoded the remaining 8% too, reading the entire DNA from end to end. The complete roadmap of the human genome is a window into human evolution, the uniqueness of different species, and disease management.

In a series of six papers published in the journal Science on Thursday, scientists delivered the most gapless, complete sequence of the human genome to ever exist (barring an errant chromosome here and there).

What’s new about the current examination is it adds almost 400 million letters to pre-existing research, one almost equal to an entire chromosome. A quick biology lesson: Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is the locus of life and information in all living cells, every gene is made up of DNA. The sum total of an organism’s DNA is what makes the human genome. The more one knows about the human genome, the better picture one will have about how we form as an individual organism, what makes us different from other species, what makes us susceptible to diseases, and how we have evolved. The DNA crammed into our cells records every detail of our life and our histories; understanding that complexity and nuance is a leap times two.

“Truly finishing the human genome sequence was like putting on a new pair of glasses,” said bioinformatician Adam Phillippy of the US National Human Genome Research Institute. “Now that we can clearly see everything, we are one step closer to understanding what it all means.”

Related on The Swaddle:

Risk‑Taking Might Be Determined by Our DNA, Finds Study

In hindsight, what made it difficult to map the remaining 8% of the human genome? It’s an incredibly complex string of molecules; scientists note the unmapped areas contained repetitive DNA regions “which made it challenging to string the DNA together in the correct order using previous sequencing methods,” CNN noted.

The process of sequencing is similar to that of taking a solved puzzle, breaking it apart, and then piecing it back together. The human DNA is broken into smaller parts, and is put together in the right order with the help of sequencing machines. These machines come with their own fallibilities while trying to make sense of thousands of pieces that look more or less the same.

In the current exploration, the research heralded by The Human Genome Project relied on improving sequencing technologies and the integrated effort of more than 100 scientists globally. Moreover, the technologies back then were also patchy in their own way; one technique was to rely on blood draws which may have introduced errors and gaps in the whole endeavor. Michael Schatz, professor of computer science and biology at Johns Hopkins University and another senior author of the same paper, told Time: “We always knew there were parts missing, but I don’t think any of us appreciated how extensive they were, or how interesting.”

Now there is a newly-unveiled reference map for how human biology evolved and what makes it unique. These freshly sequenced genes unveil the previously inaccessible section called “centrometers.”The centrometers is a fundamental part of how the DNA replicates itself, how the cells divide, how the chromosomes organize. Naturally, this region determines the trajectory of human development and plays a role in brain growth. “It’s been one of the great mysteries of biology that all eukaryotes—all plants, animals, people, trees, flowers and higher organisms—have centromeres. But it’s been a great paradox, because while its function has been around for billions of years, it was almost impossible to study because we didn’t have a centromere sequence to look at. Now we finally do,” said Michael Schatz, professor of computer science and biology at Johns Hopkins University and another senior author.

Arguably, these are new roads for genetic diversity. “The field at large is still grappling with how to resolve historical injustices in genome science and the lack of diversity in genetic studies which threatens to exacerbate healthcare disparities,” as ScienceDirect noted. No wonder the next step for the researchers in this saga of genome exploration is to sequence people’s genes from across the world — that would bare the full variation of our genetics with profound clarity.

“The complete human genome is making accessible for the first time hundreds of genes and parts of genes that we know are important to human health but were difficult to sequence and assay,” told study author Evan Eichler, a researcher at the University of Washington School of Medicine, told Gizmodo. “As such, we will have more power to make genetic associations with disease and thereby make new discoveries.”

“We’ll start with dozens and then hundreds and ultimately have thousands, so we will better represent the diversity of human genomes,” Eichler said.

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Desert Sands ‘Breathe’ Water Vapor, Research Shows