Every year, around 6 million people visit the Louvre to experience the unknowable smile of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” and the mysterious gaze that seems to follow viewers around the room. The titular Italian Renaissance noblewoman has even lent her name to the artistic effect of eyes that follow viewers, no matter where they’re standing. Except, now, science is debunking the link entirely. While the Mona Lisa Effect is real, the actual “Mona Lisa” does not demonstrate it.

Science is a buzzkill sometimes.

First a bit of background: The gaze of any two-dimensional painting or image with three-dimensional shading, in which the subject is facing viewers head-on at 0 degrees, will seem to follow viewers as they move.

“With a slightly sideward glance, you may still feel as if you were being looked at. This was perceived as if the portrayed person were looking at your ear, and corresponds to about 5 degrees from a normal viewing distance,” explains Gernot Horstmann, PhD, a member of the Neuro-Cognitive Psychology research group at Bielefeld University’s department of psychology, who specializes in eye movement and attention. Horstmann is one of the authors of the new, myth-busting study. “But as the angle increases, you would not have the impression of being looked at.”

The gaze angle on the “Mona Lisa,” in fact, is 15.4 degrees — somewhere over your right shoulder — Horstmann and colleagues determined from more than 2000 perception assessments involving 24 viewers.

Rather than qualify as an example of its eponymous effect, the “Mona Lisa” only “illustrates the strong desire to be looked at and to be someone else’s centre of attention — to be relevant to someone, even if you don’t know the person at all,” Horstmann says.

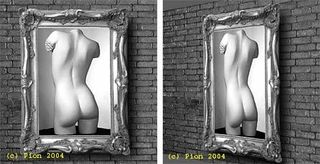

Thus, art aficionados are only left with the mystery of the painting’s smile. And for anyone who has that desire to be looked at, there are plenty of other images that do, in fact, qualify for the Mona Lisa Effect — some which don’t even involve eyes, as neuroscientist Tom Stafford explained back in 2004:

Image courtesy of Mind Hacks

In spite of the new findings, it’s unlikely the name for the perceptual experience will change — if only because the Mona Lisa Effect has a classier ring to it than the Mooning Effect.