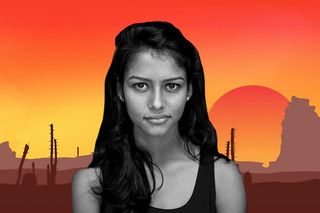

Seasonal Affective Disorder Works in Reverse in Warmer Climates

You can be SAD when it’s sunny.

The term “seasonal affective disorder” (SAD) was first coined in the 1980s, and by now, the condition’s causes and adverse effects are well documented. In temperate climates, like in the United States, SAD typically occurs in the winter months, and is associated with reduced sunlight exposure. But in the warmer parts of India, the reverse is true: It’s actually more common to experience seasonal affective disorder during sunny, summer months.

This sister phenomenon, reverse SAD (also known by a Lana Del Rey-approved nickname, ‘summertime sadness’) only accounts for 10% of all SAD cases, but studies have shown that in India, it’s actually more prevalent than regular SAD.

Unfortunately, while there’s plenty of research out there on winter SAD, very little exists on summer depression, and even less on summer depression in India. What we do know is that in both winter and summer, people who experience seasonal affective disorder often have altered serotonin levels and disrupted sleep patterns, but can exhibit any of the symptoms on the spectrum of a major depressive episode.

Also in summer depression, “what starts happening is that the appetite either increases or decreases completely,” explains clinical psychologist Varsha Makhija, who has treated many summer SAD cases in India. “There’s a huge craving to start eating a lot of carbohydrates. Or you absolutely want to stay away and you eat very, very little because it makes you feel sick.”

Beyond this, it’s fairly speculative. In the summer, one of the factors that experts think may be causing these symptoms is the temperature. The oppressive summer heat characteristic to many of India’s equatorial climes often fosters a culture of avoiding the sun.

“Because of the heat, we’ve been told, culturally, that we should go out early in the morning, or late evening,” explains Mumbai-based consultant psychotherapist Alaokika Bharwani. “A lot of it is also common sense — ‘don’t go out, you might get a [sun] stroke.’”

Research suggests heat may also directly affect mood, possibly by causing changes in estrogen levels.

“What stops everyone from going out is that you want to avoid the heat, and the mood swings, and the tiredness, and the dehydration that you start feeling when going out,” says Makhija.

This is especially detrimental when the heat prevents a person from doing activities that would otherwise regulate mood — exercise, for instance. Makhija describes this phenomenon as a “Catch-22,” because not exercising can contribute to mood swings and feelings of depression.

“This in turn also affects your sleep,” she says. “If you actually go to a therapist and say ‘I have SAD,’ they’ll actually tell you to do the opposite … they’ll tell you: you definitely need to work out more, so your body sweats the heat out.”

Both kinds of seasonal depression occur more frequently in women than it does in men, possibly due to hormone fluctuations but also to societal pressure on appearance.

In the summer heat, “there’s a lot more skin breakouts, your hair starts getting a lot more frizzy,” says Makhija. “There’s a lot of attention [on] outward appearances.”

Another possible driver of reverse seasonal affective disorder in women is a cultural aspiration to paler skin tones.

“Of course, since in the summertime, there is more heat, and there is more exposure to sun, there is a lot of social pressure, so that girls do not want to go out,” says assistant law professor Neha Mishra, who authored India and Colorism: The Finer Nuances.

While neither Makhija nor Bharwani has seen a link between colorism and summer SAD in their practices, Makhija does acknowledge that concern about UV rays can affect women’s behaviour. On a recent trip to Dubai, “I actually realized a lot of female friends, a lot of female drivers were all wearing gloves,” she says. “They thought that [their hands] would get a lot more tanned during the summer – but it doesn’t stop them from going out.”

Mishra has noticed similar patterns back home. “We have even swimming costumes which are full-length, and I have seen women wearing that in swimming pools,” says Mishra, “women who are covering their whole bodies because they don’t want sun tan or more sun exposure, which I feel is ridiculous.”

Whether or not these social pressures to avoid tanning and the actions women take in response to them have a substantial link to summer SAD remains to be seen. For now, experts agree that Indian culture does not encourage much time spent outside, especially in middle to upper class stratas of society, and that this may well be contributing to feelings of depression.

“We’re at home, we walk to an AC car, we work in an AC office,” says Bharwani. “It’s an unnatural setting. You’re spending a good 10-15 hours a day in a room, in an AC [environment], in a restricted environment.”

In order to abate the negative effects of SAD in a country where going outside often feels like it isn’t an option, Makhija recommends paying careful attention to diet, exercise, and sleep patterns. In addition to regular exercise, she notes, “make sure you eat … smaller 2-hourly meals [and] sip on more water. And [therapists will] tell you to be a lot more particular about your sleep, because all three of [these factors] will start affecting your serotonin and your body, which will affect your mood.”

Urvija Banerji is the Features Editor at The Swaddle, and has previously written for Rolling Stone India and Atlas Obscura. When she's not writing, she can be found in her kitchen, painting, cooking, picking fights online, and consuming large amounts of coffee (often concurrently).

Related

The Kind of Exercise That Actually Extends Your Life