Why We See Swirling Colors When Our Eyes Are Closed

Basically, the inside of our eyes glow in the dark.

Try it — close your eye; I’ll wait.

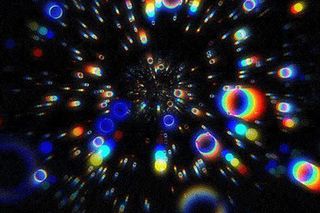

Welcome back! What’s the first thing you saw? Most people see splashes of colors and flashes of light on a not-quite-jet-black background when their eyes are closed. It’s a phenomenon called phosphene, and it boils down to this: Our visual system — eyes and brains — don’t shut off when denied light.

Let’s start with the almost-black background. The color black is often referred to as the absence of light, but when it comes to the human visual system, eigengrau is the color perceived in the absence of light. Eigengrau is a German term that roughly translates to ‘intrinsic gray’ or ‘own gray.’ When deprived of light — as in when our eyes are closed, or when we are in darkness with our eyes open — we are unable to perceive true blackness, and rather, perceive eigengrau. This is because light provides the contrast necessary to perceive darker-ness. For instance, the black ink of text might appear darker than eigengrau because the whiteness of the page provides the contrast the eyes need to understand black.

But eigengrau is not a static color. It can change shades of gray, and it can be interrupted by phosphenes.

You can think of your visual system, when your eyes are closed, like a recording camera with the lens cap on. The camera is still fully functional. It’s still recording and storing away minutes and hours of data — it’s just not very interesting data. In the same way, our retinas remain fully functional even with our eyes closed. The retina is the layer of light-sensitive cells at the back of the eyeball; it records stimuli and transmits impulses through the optic nerve to the brain, which compiles them into a visual image.

Related on The Swaddle:

What Are Those Butterflies in Your Stomach?

Scientists used to think phosphenes were our brain’s attempt to make sense out of lightless stimulation. But while people who have been blind since birth (whole-system failure) do not experience phosphenes, people who lost their vision from a disease or accident (partial-system failure) still can, suggesting something else is at play. Now, research suggests that retinal noise occurs not in response to zero light, but rather in response to a very specific type of light — self-generated light.

Biophotonic light is the kind of light generated by fireflies, glow-in-the-dark deep-sea creatures — and our own retinas when our eyes are closed. But our retinas aren’t equipped to distinguish foreign, open-eyed light from biophotonic, closed-eyed light. Therefore, our optic nerve continues to transmit the stimulation, and our brain continues to unscramble it and label it as ‘real’ or as fake — a phosphene.

Researchers suspect other parts of the eye also generate biophotons, since phosphenes are known to originate in different parts of the visual system and can even be induced artificially by taking drugs, or by applying pressure, or electrical stimulation.

“Different atoms and molecules emit photons of different wavelengths, which is why we see different colors,” reported Hanneke Weitering for Science Line in 2014. In fact, long before scientists considered the possibility of biophotonic light at play, researchers in the 1950s identified and indexed 15 phosphene patterns, and their common variations. “A phosphene with an orderly geometric pattern like a checkerboard may have originated in a section of the retina where millions of light-collecting cells are arranged in a similarly organized pattern. Researchers have also found that different areas of the brain’s visual cortex create certain specific shapes of phosphenes,” Weitering writes.

In other words, our visual systems, with eyes shut, are like a camera set to record with the lens cap on — and the camera lens itself coated in glow-in-the-dark paint. It’s still recording and storing away minutes and hours of data — it’s just weird, freaky data that doesn’t make sense.

So, the next time you close your eyes, just remember: you are a shining light — at least in your own world.

Liesl Goecker is The Swaddle's managing editor.

Related

Study: Adolescents Who Conform to Gender Stereotypes Are More Likely to Have Health Problems Later