Sexist Design Makes It More Difficult for Women to Navigate the World

Unfortunately, most spacial and product design only takes into account the experiences of men.

Design means “changing existing circumstances into preferred ones,” writes Herbert Simon, an American psychologist and sociologist, in his 1969 article “Sciences of the Artificial.” Yet, too often, the only individuals whose circumstances are made more preferable are men. Gender gaps in design are observed all over the world, and to a large extent, are accepted as normal.

Recently, this was exemplified when NASA announced its first all-female space walk — and then had to cancel it because the International Space Station didn’t have enough space suits that fit women. While nearly one-third of all NASAs astronauts are women, the ISS had only one medium-sized space suit. Despite actively recruiting women, NASA didn’t account for the physical differences between men and women’s body sizes, thus preventing its female astronauts from doing their jobs at the same time.

I have seen this gendered failure of design first-hand through my work as an inclusion and gender development specialist who has worked on national and regional development programs for over a decade. I once worked with an international development bank, which, months after the completion of an expensive handpump project in a northwestern Indian state, was left scratching its head when the handpumps weren’t being used by the women they were intended to help. The engineer, designer, manufacturer, installer and monitoring officials were all men, making a product for women, and the existing patriarchy didn’t allow for dialogue between officials and the women responsible for drawing water.

When these women were finally consulted, the dialogue revealed that the handpumps were too high and too difficult for the women to use. The chasm between what women needed and what men thought would help them led to an expensive and unfortunate error.

When products are designed only keeping men in mind, the negative impact on women can be immense. Take SexFit, a ‘pedometer’ for the penis that measures thrusts and impact, accounting only for what constitutes male satisfaction. The sex toy stirs up toxic masculinity by reducing intercourse to penile penetration and a count of competitive thrusts — the gadget collects data, which like other fitness apps, allows the user to share and compare data. The value of the vagina is reduced to an impersonal receptacle.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the Design of India’s Cities Is Feeding Gender Inequality

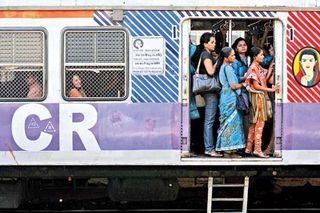

Another example, well observed in Mumbai, involve the city’s local trains. Almost everything designed in and around those trains are designed for men. The height of the floor boards creates a sizeable gap with the platform. Every year these gaps claim victims of both genders, but women are disproportionately hampered in scaling these gaps by being shorter, on average, and often wearing saris, which are not convenient garments for leaping. Women also tend to carry more bags/luggage and have small children in tow. The handles for standing commuters in the women’s compartment are at the same height as the general compartment, though women are, on average, almost 14 centimeters shorter than men.

Even the design of stations is not considerate of women’s experiences: The ladies first class compartment has elicited complaints over a long time for its position: it stops right in front of the male restroom at most stations. There are many problems with this, ranging from the unpleasant, like smell emitting from the toilet block, to the risky — the toilet block is an isolated area of the platform, frequented by men only, which creates more opportunity for harassment of the women who are forced to frequent its area; the first-class women’s compartment has the fewest commuters especially off-peak hours, enhancing risk.

Only in recent years have certain automobile companies in the West begun using crash test dummies modelled after the average female body — for some tests. The move was in response to research from the University of Virginia, which found women are 71% more likely than men to experience moderate injuries under the same crash circumstances. Safety reviews of cars that are not designed for the average female body consider the seat adjustments that most women must make to reach the pedals and look over the dashboard to be “out of position.” Automobile design and engineering are male-dominated professions; it likely never occurred to these companies to design for someone unlike themselves.

Related on The Swaddle:

How the Design of India’s Family Flats Is Changing

More frequently, however, large data gaps persist. For instance, while accident reports for Mumbai local railways are probably some of the best in the country, the data they compile is not broken down by gender. To recognize that women are disproportionately affected by gender blind design, adequate data needs to be collected. The world is slowly moving toward that; in 2011, the World Bank recommended its transport unit in India take a count of total male and female commuters and accident victims.

But solutions can start even before the data is gathered. Like in any other field of work, female representation in design and its deployment needs to be seen and heard. In another instance in my career, I was part of an infrastructure planning team for a public transportation project. A room full of male engineers, designers and planners were trying their best to think like a woman with heavy bags, who needed to go up from the platform, or down to it, hitting on an elevator as the solution. Not being women themselves, it never occurred to them that during off-peak hours, especially in the winter or heavy monsoon, or just late at night, a woman would not want her only option to be an enclosed space with unknown men. It heightens actual risk, perception of risk and overall uneasiness, I explained. Ultimately, escalators were pursued instead.

Inclusive design is important. If ignored or justified by ‘cultural norms,’ the effects can be harmful, long-lasting and expensive. Some of the best cities in the world, are also some of the safest for women and men alike and permit equitable access of public spaces and services. From products to space suits, to mass transit, design needs to be gender informed. STEM topics — science, technology, engineering and math, all of which inform design — have been perceived as subjects more suitable for male students, a social construct that could use some adjustment. Subsequently, employment and career growth of women in these fields would ensure more female perspectives are involved, or even in the lead.

In the meantime, the mere act of asking and listening to women can go a long way toward “changing existing circumstances into preferred ones” — for everyone.

Sonali David is a development professional with three masters degrees who not too long ago realized inclusion and gender were where her heart lay. She's worked for more than a decade with the Government of India, United Nations, World Bank and a few others on national and regional level development programs and projects, particularly in the WASH and transport sectors. When she's not busy analyzing inclusion and gender blindness across society, Sonali plays mom to her two Great Danes. She's an amateur gardener, artist and baker who loves CrossFit and dead lifts. She speaks five languages and has lived in six Indian cities.

Related

Know Your Rights: Alimony in India