‘Shakuntala Devi’ Leans Into Tired Indian Tropes of Boastful Intelligence and Parental Control

Intelligence is a pursuit of showmanship, rather than scholarship, in this depiction of the world-record holding calculation whiz.

The Indian experience is incomplete without children who, at the behest of effusive parents, present their talents to a group of gawking family elders. Shakuntala Devi’s abilities are treated similarly in the new Amazon Prime biopic on the prodigy’s life.

The real Shakuntala Devi was born to poor Kannada Brahman parents, and rose to international fame for her unbelievable calculation abilities. Devi’s fame served the purpose of bringing people’s attention to math as an area of interest, and Indian intellect as a thing to be reckoned with. Indira Gandhi once said to Devi, “Out of all the ambassadors for India…you are the best.” The biopic, framed around Devi’s daughter Anupama Banerji’s experience of living with her mother, is a story of how three generations of mothers grow to accept their flaws and mend relationships with their daughters. But Devi’s immense aptitude for mathematics and her desire to make money off it in a sexist, colonial society is the sort of story that could also make her a feminist hero for young girls, especially those who want to pursue STEM fields.

Yet, there is something deeply off-putting about watching Shakuntala Devi’s abilities glorified in this manner. Devi is portrayed as a globally renowned Indian intellectual and scholar, even though her contributions are mostly the performance of high-aptitude calculative abilities that she did not need any formal education or training to achieve. Plus, Devi, known for her ‘scientific temper,’ has also openly promoted and participated in pseudosciences, like astrology and Vedic mathematics.

Normally, there would be a clear distinction between a woman with high mathematical aptitude, and a scholar who dedicates their life to the study of a subject. But, the Indian ideal of intelligence is not scholarship or scientific temper. Rather, it is the display of high-aptitude for STEM and the validation it can fetch from global eyes. This is why Shakuntala Devi chooses to glorify Devi’s calculation performances with the cadence of a superhero movie — her global fame is the validation of India’s brainpower. Therefore, we continue to call her a ‘mathematician’ and glorify her high aptitude incorrectly as ‘scholarly.’

Related on The Swaddle:

Exploring Giftedness: Is a Child Prodigy Born or Made?

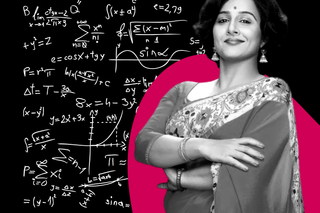

The film creates the ideal Indian heroine to take on the world with her intelligence and values. Vidya Balan as Shakuntala Devi always wears sarees on stage, has an awkward South Indian accent, and passionately talks back to the British in dialogue that should’ve stayed in the script’s first draft. She also adopts vidya kasam as a catchphrase, denotes the worship of ‘vidya’ or scholarship. The latter, when combined with traditionalist attire, manner of speaking, and voluntarily pursuing Brahminical pseudosciences like astrology and Vedic maths, feel like the film is subtly reinforcing Brahminical dominion over STEM fields.

However, Devi’s intelligence is portrayed as that of a dabbler, interested in keeping up appearances of intellect, rather than serious scholarship. Devi’s attempt to study homosexuality as portrayed in the film is one example. According to what Devi’s daughter recollects, Devi falsely calls her ex-husband Paritosh Banerji queer, as a means to create a ‘personal experience’ that would sell her book on queerness better. While many contest that this does not dent Devi’s allyship — it does showcase an insensitivity and arrogance in Devi’s approach to analysis.

Related on The Swaddle:

The Indian Study Abroad Dream Is Dashed. Will We Finally Redefine Success?

Shakuntala Devi‘s depiction of motherhood is the only time we get to see the prodigy’s complex side. Devi remains consistently unlikable, but this time, her failure at parenting her child well rouses empathy in the viewer. The film depicts Devi’s own childhood as devoid of her mother’s love, especially when her mother refuses to stand up to Devi’s father for the children, and only asks Devi for money after she leaves home. This leads to Devi becoming an overly-attached parent, who takes her daughter Anupama everywhere with her, while not allowing Anupama’s to read the letters her father sent for her. Anupama slowly starts to resent Devi for always prioritizing work over letting her have a normal family, and blows up when she finds out Devi lied about her father’s sexual orientation.

Devi flails at motherhood, thinking her natural intellect, feminism and good intentions make her fundamentally correct at every parenting decision she makes. On multiple occasions, she points to the stitches she received while giving birth as justification for her choices. The film puts forth the idea that all mothers are flawed, yet deserving of the ability to redeem themselves — a kindness rarely shown to female characters in Hindi cinema.

Yet, Devi’s idea of motherhood seems to be owning one’s daughter. Her husband loosely tells her that children always have a right to their parents, but parents must let go in order for children to progress — an idea Devi thoroughly rejects. Devi is dismissive of her daughter’s choices and needs if they do not align with her own image. She does not want her daughter to achieve independence, marry the man she wants, and live in the city she wants — all because it is unbecoming of Shakuntala Devi’s daughter to do so. Devi paints her daughter’s needs as feminist failures, making her daughter resent Devi and anything to do with her (including math, a subject she enjoyed as a child). But, even as Devi’s daughter tries to escape her, Devi piles affection and attention upon her, promising to do better. And Anupama, deprived of healthy love and attention, snaps back into her mother’s arms like clockwork. For every time Devi wrongs her daughter — faking her ex-husband’s queerness, or selling all her daughter’s property investments — the film shows Devi attempting to redeem herself with gestures like staying in with her daughter for the weekend, or making a scrapbook. This, according to the film’s treatment of the incidences, is a positive showcase of mother’s love. The film expects the audience to excuse Devi’s behavior by virtue of her warm motherly impulses, rather than clearly depicting her actions as means of control.

Shakuntala Devi, both real and reel, is a complex woman who devoted her life to a splendid performance of her calculative skills. The film, however, subscribes to over-enthusiastic heroism, partly via Vidya Balan’s loud, caricaturish rendition of the titular character. While Devi’s life is a matter of intrigue, it is not the sort of life that can be used to ‘inspire’ young girls to pick up STEM fields. This is because real-life Devi chose to further pseudosciences, rather than actual STEM fields. And because reel-life Devi sees her natural intellect as a means to achieve fame and power only, rather than as a means to contribute to research. India still heavily under-funds STEM-based research, leading to a culture that values STEM fields only to snag high-paying corporate management jobs. In an environment of low scientific investment and curiosity, this is not the heroine we currently need.

Aditi Murti is a culture writer at The Swaddle. Previously, she worked as a freelance journalist focused on gender and cities. Find her on social media @aditimurti.

Related

Work, Re‑cultured: A 24‑Year‑Old Lawyer Struggles With Virtual Hearings