Social Media Is Shaping Our Memory of Wars, Pandemic. What Will That Mean for History?

“Social media platforms were never set up to be serious archives — but, of course, they could very well become that.”

For more than one year, Delhi’s edges thronged with resistance. Tractor marches paraded the streets, negotiations took place around fires and in the parliament.

But this one year is stunningly muddled in collective memory. For some, the protest was radical, violent, and conspiratorial – courtesy of misinformation around the violence at Red Fort. A 23-year-old activist’s online toolkit to support millions of farmers became evidence of malice. A 180-degree turn brings us to social media posts documenting memories of the unbridled warmth and potency that lived in each tent on the Singhu border. It was a fight of resistance unseen since the partition.

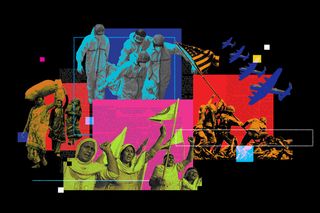

Throughout history, mass media has influenced what we remember and how we remember it. Today, a staggering incongruity plays out on the internet; real-time documentation acknowledges a truth, warps another, forgets yet another, birthing a response archive unlike before.

Social media aesthetics create a patchwork account of reality. “The various forms of content disorientingly overlap—the professional with the amateur, the intentional with the incidental,” as The New Yorker noted. Hard evidence of wars and violence “suddenly punctures the placelessness of the Internet, reminding viewers that they are watching a real person in real danger.” The war in Ukraine, for instance, is set against a nifty tune on TikTok and the story of the second Covid19 wave in India is scattered across Instagram posts, Twitter calls for help, and official accounts claiming India’s success.

This style of info-documentation – one reflexive to every minutia – informs how we construct historical narratives. And like every archive of memory, pitfalls remain. Who is writing it and based on what source? What do we consider and what is left out? What of the “noise” becomes history?

Dr. Payal Arora, a digital anthropologist, and professor of global media cultures at Erasmus University Rotterdam, notes that behind the choices about what is called news and what isn’t, lies a political economy of funding. “Which stories get told, which groups are humanized more than others, and how much nuance can one add to this story. Sadly, documentation of this kind is often driven by state ideologies to simplify narratives, rather than reflect complexities on the ground.”

Archiving through social media thus presents a very complex issue. “When we chronicle the present we really don’t have a sense of what it means in terms of the long arc of history,” explains Dr. Arora.

There is much to be said about misinformation and disinformation. How social media plays out during a war, or a health crisis functions like social media during any other time in modern history. We continue to swipe because things are fun, engaging, or immediate – not because they are always true.

It is a truth of our times that people are impatient, less willing to do the mental work that is needed to seek information and process it carefully. Either they accept projected expertise unquestioningly or they are skeptical of everything. “Very few people,” notes Usha Raman, a professor of media studies at the University of Hyderabad, “have the tools to be able to critically evaluate the abundance of information that is thrown at us, and then make sense of it objectively.” Arguably, it is infinitely easier today to consume information without questioning its source, credibility, or what impact it has on us.

Related on The Swaddle:

This fast-paced culture and short-lived memories mean crises are remembered as mere summaries; they said-they said narratives that blurs the line between fact and fiction. For many, 10-second, highly decontextualized videos on Instagram or TikTok become the primary source of information.

As a result, when this is viewed as a past event, it becomes marred with incredulity and doubt. And when the onus is on the people to prove authenticity, it adds to mass helplessness and leads people to fill the information gap with their own biases.

“Social media provides a wealth of alternative streams of storytelling from diverse groups, including those who have long been marginalized. However, there needs to be a concerted effort to bring these threads of often raw data together in a way that helps people make sense of the realities of our day,” Dr. Arora notes. A lot of groundwork needs to be laid to ensure these stories stand the test of time.

Social media also exists under the rule of algorithms, which means some information may be prioritized for posterity while others are bound to get buried. Any number of factors may determine this – the geography, scope of content, if it’s a video or a picture, who is sharing it.

Take this picture of a child in Kashmir, crying for his father who was mistaken for a terrorist and shot by armed forces. How many people this content is shown to by the algorithm – and subsequently how many of them like/retweet it – determines how profoundly this moment in time is remembered. Such a way of curating important events makes one more apathetic, dissociated, and distant from reality. It sows dread, fosters inaction, and embeds a worldview of distraught negativity.

According to Pathak-Shelat, an information overload on social media leads to “escapism to avoid having to act, and unwillingness to respond [to events].” All this too has a bearing on how these events are remembered in history.

***

“There is that great proverb,” said author Chinua Achebe in a 1994 interview, “that until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

The aphorism carries many truths but also speaks to why, despite all its pitfalls, the social media era is also the golden age of journalism. Before social media and citizen journalism became mainstream, the power to control what will be recorded, and how, rested with a select few.

When thinking of social media wars, in particular, our collective memory immediately darts back to the Arab Spring of 2011, when real-time reporting from the ground was sufficient to aid the historic fall of governments. The account of the people – which forever exists on the internet – directly contradicts the state narratives of the time. That is, how information is disseminated via social media can not only change the course of history but also, without the internet, our memory of these events would be very different.

Related on The Swaddle:

One Year Later, Are We at Risk of Forgetting the Lessons We Learned During the Pandemic?

“We humans are partial to neat and simplified narratives and we are used to the conventional way of recording history as a single story,” says Manisha Pathak-Shelat, Ph.D. in mass communication from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and a professor at MICA. In this narrative, there is a conventional person of authority – with clear cult binaries of us and them, heroes and villains.

A new style of documenting reality can disrupt this binary. For one, the number of voices contributing to archiving increases. “One obvious advantage is that it allows everyone to document and share in real-time, without the need for either sophisticated equipment or access to special networks such as mainstream media,” says Raman. The ability of individuals to reach large audiences thus disrupts “the dominance of a single narrative.”

Social-media archival in the form of reels and videos also make real-time events more immediate and immersive; think of the TikTok reels with people documenting their everyday life during the ongoing war on Ukraine – cooking, sitting in bunkers, even dancing to protect their mental health. “These bits of information do give you a sense of control in a moment of utter chaos around you,” said Rita Konaev at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology.

It is no wonder crowdsourced citizen archives – museums of individual memory – are becoming increasingly important records of history, reflecting narratives that would be otherwise forgotten.

Historical records benefit from this plurality. “The monopolistic narrative has given way to a polysemic and pluralistic storytelling which is, of course, chaotic as there is no single, simplified and neat story anymore,” Pathak-Shelat says. “History is being chronicled in multiple voices as it is being lived.”

Further, as Raman notes, “during major wars, most media tend to become fairly inward-looking and nationalistic to some extent, so in today’s scenario, at least we can sample media from across the world to arrive at a nuanced picture … People talking to other people through social media make it harder (though not impossible) for propaganda to go unchallenged.”

It is then obvious why increasingly common in the playbook of revisionist history that one of the first things autocratic regimes do is to cut access to social media. Right now, the Russian government has cut off public access to social media like Instagram. The narrative currently within reach for most Russians is of Russia “helping” Ukrainians – of freeing them from oppression. It is becoming increasingly evident then that in the playbook of revisionist history, one of the first things autocratic regimes do is to cut access to social media.

***

Arguably, the issue of ephemerality doesn’t go away; any information documented for a social media-first format relies on algorithms and a short attention span. “But it is ephemeral to the platform by design and the viewing of the moment. Once captured, the actual content remains, somewhere, to be added to an archive of memory if one wishes,” Raman adds.

Pathak-Shelat also notes the need for history to be understood “as vignettes – not as carefully filtered and dressed facts but as situated perspectives and perceptions.”

What sense does the social media generation make of history then? According to Dr. Arora, there remain contradictions in any narrative of history. These are not seamless narratives building a singular account – but one where nuance would dominate if we were “to unpack it,” a world “where good guys can also be the bad guys and what was right for some was also wrong for others.” It demands an interrogation of the perception of archives in the place – ones that are not dead documents on the shelf but living spaces that are dynamically changing as we continue to engage with them in diverse ways.

“We panic about such perceived dissonance, but we really shouldn’t,” Dr. Arora says. “Social experience is not compartmentalized, nor should it be.” People humor in tragedy often as a coping mechanism, just like they find a cat reel to assuage their anxiety about a global crisis.

In this distortion of reality, there is a notable loss of a simplified means of mass media – such as the television. But this is not exactly a “loss.” “We romanticize efficiency as ideal and no wonder… Diversity is of course messier, more complicated, and difficult to control,” Dr. Arora says. “Social media is an imperfect chronicler of wartime. In some cases, it may also be the most reliable source we have,” as one commentator noted.

In the light of our phone screens, which help us see nine seconds of half-truths, the hope is to understand the limits of our knowledge. “I don’t think social media platforms were ever set up to be serious archives for future historians–but of course, they could well become that,” Raman notes.

According to Pathak-Shelat, this will require sensitive historians who “can capture these multiple angles well and let conflicting voices tell their side of the story.” Readers of this history too will need to “put in more work into making sense of these entangled narratives.”

What would do better than focusing on these binaries is to demand credibility and accountability from any information we engage with. There is a reason the idea of regulating information online in an age of algorithms is seen as a “human rights issue.”

Social media is an ever-morphing construct – a collective dream we fall into once in a while. What will we remember, when we wake up?

Saumya Kalia is an Associate Editor at The Swaddle. Her journalism and writing explore issues of social justice, digital sub-cultures, media ecosystem, literature, and memory as they cut across socio-cultural periods. You can reach her at @Saumya_Kalia.

Related

Will Smith’s Oscar ‘Smack’ Forces Us to Re‑examine the Kind of Humor We Find Acceptable